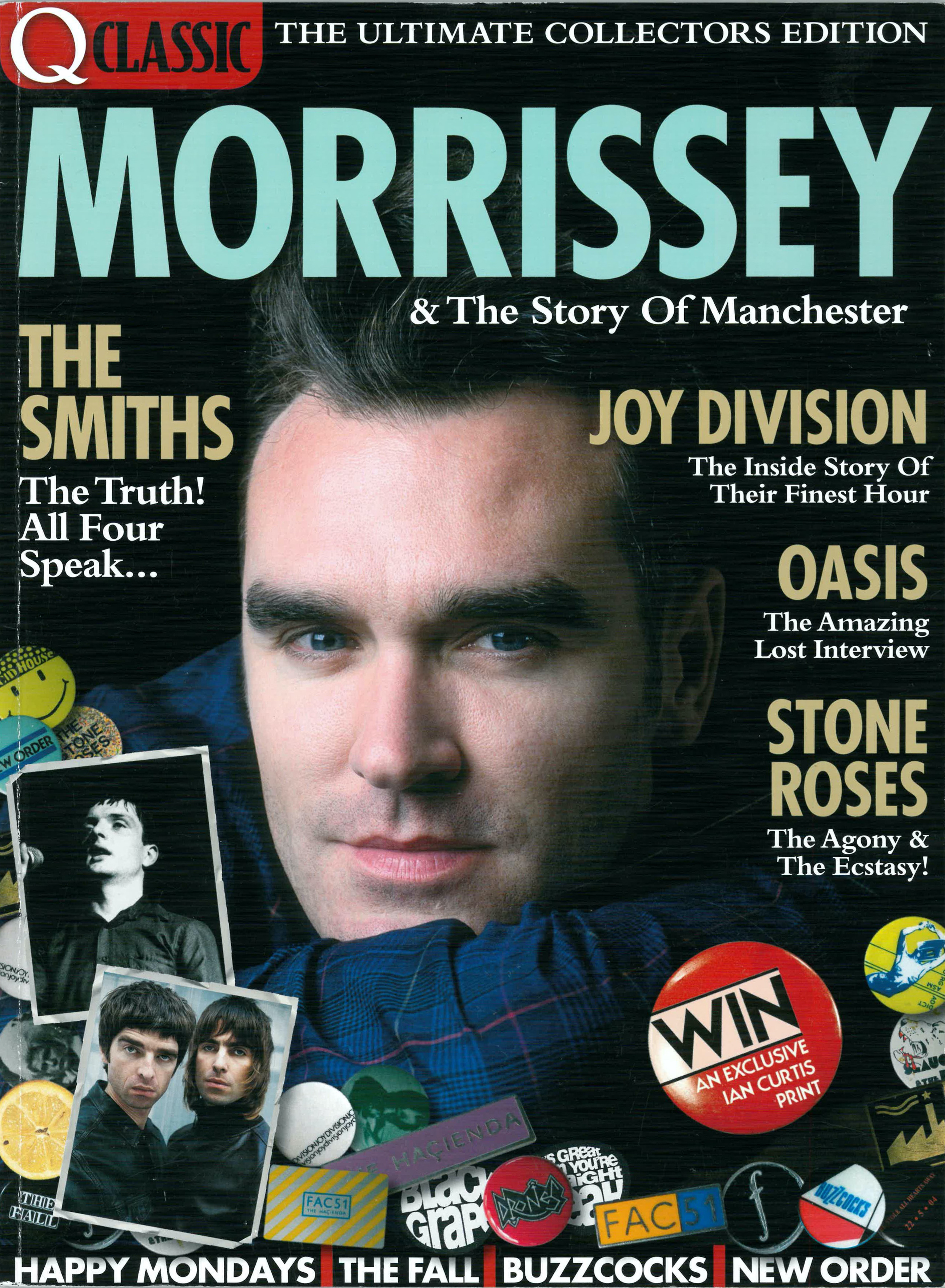

2006 03 Q Classic Morrissey and The Story of Manchester - Part 1

Industrial Strength

How did the world’s first industrial city become the crucible of late 20th century musical innovation? John Harris explains...

MIDWAY THROUGH THE 19th century, a man with the improbable name of Angus Bethune Reach wrote a remarkable article about Manchester in the daily Morning Chronicle. It found the author returning home one night and being surprised “to hear loud sounds of music and jollity which floated out of public house windows”. He went on: "In no city have I ever witnessed a scene of more open, brutal and general intemperance... The whole street rung with shouting, screaming and swearing, mingled with the jarring music of half a dozen bands.”

Give or take their air of Victorian moralism, the words could easily describe a 21st-century Mancunian Saturday night: droves of people spilling out on to Canal Street or Deansgate, their brains still rattling to the thumping strains of high-street dance music, or the kind of indie-rock that will forever take inspiration from some of the city’s most celebrated sons. In both theVictorian period and what might be termed the Late Blair Era, much the same spirit endures: a hard-wrought kind of hedonism, always entwined with an attachment to the joys of popular music.

Across the centuries, in fact, you can draw all kinds of lines between events that combine to underline the city’s historical clout. If Manchester’s early embrace of mass production gave it some claim to being the birthplace of the industrial revolution, it was surely only right that its most important record label would be called Factory,When the production line was still king, Charles Stewart Rolls was introduced to Frederick Henry Royce at the Midland Hotel on St Peter’s Square; 77 years later, Johnny Marr met Morrissey at a house in Stretford, and a very different era began. On 21 June 1948, Manchester University invented one of the world’s first computers; in the summer of 1987, down the road at the Hacienda, the city began to alert the world to the possibilities of entrancing thousands of people via digitally created music.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who made their first visit tol Manchester in July 1845, would have recognised what ties all this together. They called it Historical Materialism - essentially, the idea that if you want to understand culture, you’re best off digging underneath it to find the economic nuts and bolts that drive everything forward. With Manchester, it’s a cinch: to grasp the trailblazing mentality of the city’s musicians and the eternal Mancunian tendency to look down your nose at London, you have to return, time and again, to its history as a world-beating industrial city. Once, it carved out a dizzying reputation via cotton and free trade; when all that was over, to hear some people talk, it managed to repeat the trick using guitars, drums and turntables.

Along the way, meanwhile, came developments that crystallised the link between economics and music. In 1858, using frinds raised by the city’s industrial pre-eminence, Sir Charles Halle founded what now stands as Britain’s longest-running symphony orchestra. Seven years before that, Manchester saw the opening of the aforementioned university, eventually to give rise to one of the largest student populations in Europe, a ready audience for anyone who fancied making a living via music. In the meantime, the city became home to whole generations of immigrants, drawn by the simple promise of work - first from such European countries as Russia, Germany and Poland; then, a little later, from India, Pakistan and the Caribbean. Always, of course, there were the Irish, whose offspring would include such notable Mancunians as Morrissey and Marr, the Gallagher brothers and Shaun Ryder.

WHEN THE INDUSTRIAL dream turned rotten, Manchester may have been slowly rendered drab and dysfunctional, yet here you find the key to the city’s modern musical reputation: minds brimming with that very Mancunian desire for innovation and expression, faced with plenty to complain about, but also gifted with a mass of empty industrial property and squattable homes. Here, in retrospect, were circumstances perfectly suited to the arrival of punk, which duly occurred on 4 June 1976, when the Sex Pistols paid one of two visits to a pocket-sized venue known as the Lesser Free Trade Hall. It’s long since been a local cliche, but it merits endless repetition: the audiences at that show and the rematch on 20 July included future members of the Buzzcocks, Joy Division, Magazine, The Fall and The Smiths, plus of course local media personality and future Factory Records boss Tony Wilson.

When this generation began to make music, it perfectly reflected their post-industrial environment. This was not just a| matter of derelict factories; at the very centre of the cityscape lurked the remains of wrecked lives.“By the age of 22," Bernard Sumner once reflected, "I’d had quite a lot of loss in my life. The place where I used to live, where I had my happiest memories, all that had gone... For me, Joy Division was about the death of my community and my childhood.” As has so often been the case, decline bred artistic brilliance:as the DJ and writer Dave Haslam once put it, “Maybe if Manchester was less of a shithole, then creativity in the city would die."

2006 finds Manchester in way better shape than that would suggest. The city's musical flair eventually gave rise to bars, clubs, venues and studios. In turn, the example set by those places snowballed into the modern concept of 'regeneration', and Manchester - after dark, at least — became the very model of the Leisure City. And so we arrive, once again, at a familiar picture: as Mr Bethune Reach would have it, “general intemperance",“shouting, screaming, swearing"— and the music of dozens of bands.

Comments

Post a Comment