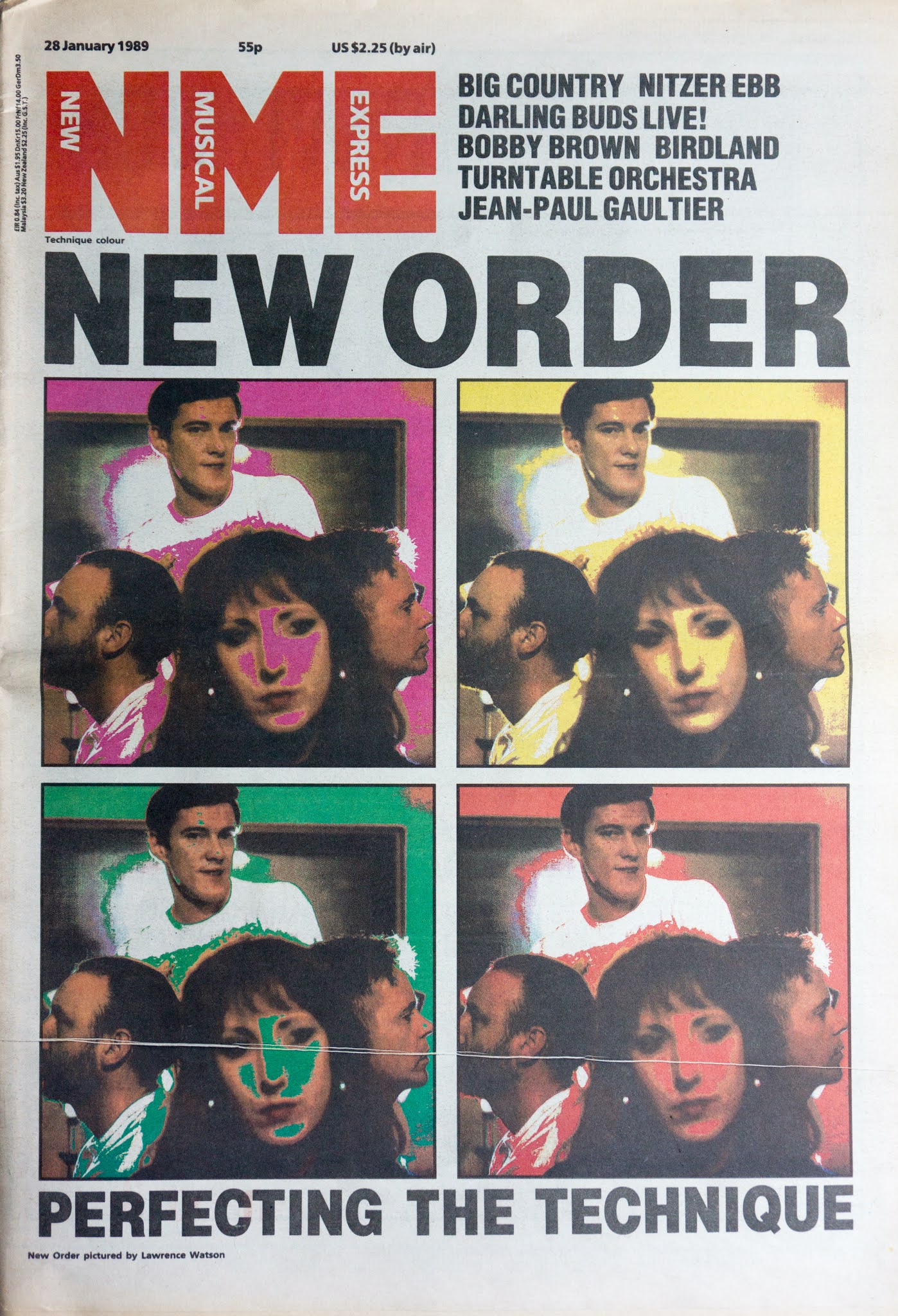

1989 01 28 NME New Order Feature

THE DREAM THAT NEVER ENDS

Touched, perhaps, by the hand of God? Certainly NEW ORDER can seem to do no wrong. Fiercely independent and singleminded, they’ve cruised through the ’80s on a fuel of unswerving critical devotion and ever-greater mass popularity. 'Technique’, their long-awaited new LP, will shoot them to still loftier peaks. An exhausted DANNY KELLY emerges from an epic in-depth interface (that's a Chinkie and a chinwag - Ed) with the band’s fine line on Bolshie builders, Acid parties, subsidised slavery, surviving mistakes, soundtracking synchronised swimming and working with Frank Sinatra. And that’s just Part One! Order border: LAWRENCE WATSON.

In my dream it's May, 1980, and Ian Curtis is late for a Joy Division practice. Hands buried deep in the pockets of that baggy mac, his purposeful walk comes to a sudden, startled stop. From the rehearsal room he was headed for comes a music of awesome rhythmic power and dizzying contrasts between shining light and impenetrable dark; it is both irresistibly physical and delicately beauteous, a muscled arm in a crystal gauntlet; it is the sound, Curtis realises, that Peter Hook, Bernard Sumner and Stephen Morris would make without him. Faced with this stark truth, he turns and runs. Away from that music and into the murk of the Manchester night. Forever.Only a dream, but footed in truth. Both 'Transmission' and 'Love Will Tear Us Apart were titanic 45s, sure, but I've never been able to fathom the near-religious adoration that Joy Division inspired. Ian Curtis' real death was for me, therefore, not the end of something magical, but the beginning, the dawn of New Order ..

In the eight-odd years that have since whistled by, Hook, Sumner, Morris and new girl Gillian Gilbert have resisted the megabucks blandishments of CBS and EMI and remained ostentatiously, pigheadedly, separate, while assembling a body of work that's veered crazily from incorrigably half-baked lows to sense-numbingly wondrous highs.

Last year's 'Substance' compilation showed just how stratospheric those highs have been and confirmed New Order as one of the great singles bands of the era. Of any era. It was a collection that would, in a more honest world, have convinced virtually every other band on the planet to hide in despair, to pack it in...

'Substance', and the '88 remix of their 'Blue Monday' anthem were a breather, a summation of the group’s unique progress and their goodbye wave to the '80s before they headed off into the future.

So now - with the afterglow of their 'Fine Time' hit still warming the Top 30’s glacial frown, and on the eve of 'Technique', their long overdue fifth LP - seems like the perfect time to talk to New Order, about the decade they've spanned and illuminated, about the spaces they presently occupy and about the motivations that drive them on. Oh yeah, and about Acid House parties, rogue police dogs and the thrill of backing Desmond Lynham!..

In my other dream, it's winter 1988 and I'm chatting to New Order in Buenos Aires, using the exotic location to combat the band's reputation for diffidence/difficulty when confronted by tape recorders.

But this dream, alas, is not to be. En route for our Argentine rendezvous, I get as far as New York while the group make it all the way to Sao Paolo, Brazil (and an audience of over 100,000), before our best laid plans are dashed by the small matter of a military coup!

Tanks in the boulevards of Buenos Aires.. .blood in the gutters... mayhem, hysteria and crisis, the full works. The lengths to which some people will go just to avoid an interview!

Thus, instead of a pavement cafe on the Plaza Del Mayo, we make do with a pricey noddle-joint in downtown Manchester. Around the table sit Stephen and Gill (lovers and New Order's percussion and keyboards respectively), the mighty Peter Hook (bassist, rock icon, resplendent in lip-crimson track bottoms) and my nervous self. We’re being basted in background muzak, glutinously sugary orchestrations of familiar poptones.

Right now, the Everly's 'Cathy’s Clown' is getting the treatment and Bernard Sumner ('Barney', NO's vocalist/lyricist/ co-tunesmith) is late. His colleagues aren't surprised. 'He's having his new house done out," they giggle. ‘He'll turn up and say ‘sorry I'm late, I've got the builders in.."

On the New Order In-Joke Chart, Barney's Sybil Fawlty-style entanglement with the construction trade currently vies for top slot with Peter Hook's imminent acquisition of a £13-a-week Youth Training "slave" to ‘make the tea in my studio'. Hook, indeed, is loudly discussing the possibilities presented by a weekly investment in these wretches of as little as £100, when the singer finally arrives. He's an altogether less agitated figure than the strings-tangled demento dance-puppet of recent Top Of The Pops notoriety.

"Sorry I'm late", he burbles, "but those flippin' builders..."

Chinese chow chewed and glasses suitably recharged, we're attempting to position New Order in rock's swirling firmament.

'Substance' has irreversibly established them as a Big Deal in America, flushing them, never to return, from their cosy 'cult' niche. Yet they’re leagues below the mammoth likes of U2 and Bon Jovi, and hairy rawk-wrestlers like Guns 'N' Roses will this year stampede past them on the trail of global hugeness. So where do New Order see themselves in this ever-shitting platinum pecking-order?

An uneasy silence (punctuated only by Peter Hook's delighted “looks like we're keeping our options open on that one!") mirrors the band’s fabled reticence before Barney, habitually the most talkative, sallies forth:

“The gun is in our hand," is his disquieting opening image, ‘it really depends what we want to do. By touring constantly and doing all the rest of that stuff we could quite possibly end up as awful as U2!...

"No, no," he chortles, ‘not as awful, as big..."

‘If we were prepared to sweat at it we'd be that big, but personally I'm not. That would take all the fun out of it; it'd become pure, out and out work...

"New Order could become this huge machine. I mean, even now getting a record out has become this big operation, like a turn of some massive cog. In Joy Division, we'd get a song and go 'yeah, let’s record this and release it' and it’d be out in a month or summat. But now.. .we've had six meetings about putting out the new LP! It's this great cumbersome manoeuvre.."

Dearie, dearie me! The awful problems of selling millions of records! Barney's line is beginning to sound like poor-little-rich-boy whining when he mercifully alters tack:

‘On the other hand, our position is fortunate. We could always be doing jobs that we hate, like so many others. and we’ve got an ever-better chance to get the music across to a lot of people, especially the straight types who wouldn't ordinarily listen to what you described as a 'cult' band. This is particularly true in America. Maybe we can help - Christ, this is going to sound patronising - to educate them a bit, musically...

".. .maybe stop them listening to sugarpop records or whatever. Maybe even", he flashes his best knowingly innocent wicked-pixie grin (the man's a scamp) ‘show them that music can be a beautiful thing..."

When the Pet Shop Boys recently announced that they were "The Smiths you can dance to", I was measurably gobsmacked. I know that there's only so many slices to be made out of the old rock'n'roll cake, but so keen an awareness of ones rivals, so naked a sense of competition, still shocked. New Order, Barney confirms, are above such vulgarity, refusing to see themselves as pitted against their contemporaries:

“It’s definitely an attitude you can take," he shrugs, "but I don't think it's very helpful. Besides, I don’t listen to many other bands. In fact. I don't listen to any."

But he does, I insist, hear music other than his own, in clubs especially. New Order own The Hacienda and Sumner's both a regular there and an enthusiastic participant, matey, in Manchester's thriving Acid House scene. He's had us doubled up, in fact, with his tale of a recent acid party, in a 14th floor flat, which was abruptly terminated by the arrival of the local police's specially starved German Shepherds. And how had the district's constabulary located this supposedly select do? Oh yeah, the flat's windows had been removed - they just followed the noise and the flashing lights!

Meanwhile, back at other, possibly competitive, music Barney hears...

"Oh sure." he nods, “people give me tapes. But I don't follow music.. I enjoy it. When I listen to those tapes I'm... well... I'm usually out of me box!"

So, if it's not the public school urge to compete and conquer, or the mere necessity of paying quarrelsome builders, just what is it that keeps up their thirst for making music? It's meant to be an easy question, but New Order, not content with the Chinese they've just scoffed, make a meat of it:

“It's the only thing I’m any good at," Peter eventually offers. "Pretty simple, eh?”

"With me," Barney follows, "it's that thing of making a record that I can play and be pleased with."

"And there's something very satisfying," muses Stephen, "about finishing up with something which you can tangibly feel and say 'yeah, that's good'."

New Order really shouldn’t be struggling with this; there’s no mystery. They've pumped out a succession of 'good’, 'pleasing' and 'satisfying' music, to say the least, and so they've got - built-in - the best reason for carrying on that any band can ever have - their own brilliance...

You’d not expect so flattering a statement to provoke mutiny in the ranks, but Peter Hook’s having none of it:

"Our 'brilliance' is just your personal opinion," he growls, "but groups don't release stuff unless they think it's good..."

I want to tell him how idealistic that sounds, and how lazy, talentless and cynical most pop bands are, but there's no stopping him now..

"... I mean, has any musician ever come to you and said 'my new record is total and utter crap? No? That's my point - its all just personal preference. It's like the guy who was trying to sign us for CBS; he genuinely thought that Paul King's solo LP - which had been really badly received and sold about three copies - was the best record he’d ever been involved in. he stood there and told us that straight! He thought it was wonderful!..."

"I think another thing that's kept us going," interjects Barney, returning to some long-neglected theme, "and where we're different from other groups, is that we started out knowing precisely f— all about music. So we're learning every time we make a record. We didn't start as musicians; we're slowly becoming musicians. And that's a very creative thing.

"I mean, if someone asked me to play a scale in E minor or something, I wouldn't know what the f—they were on about, but the point I'm making is that we don’t get bored or stale because we don't really know what we're doing, see what I mean? We haven't an established way of writing a song...”

Barney is here returning to some wafer-thin ice over which he first blithely skated in another recent interview. In that (while madly hedging his bets with the old ‘I-know-this-is-gonna-sound-nutty’ get-out) he attempted to convince us that he is some kind of aerial, picking up the vibes from the scattered mass of New Order's faithful. He went on to claim that the music and lyrics he writes, therefore, are nothing less than the collective will of that teeming horde. Something like that.

A distinct case, I venture, of B(l)arney, and a set of theories about which the human antenna is now being far less forthright:

"Well," he treads carefully, "a lot of the time you really don't know where the music comes from...

"And a lot of the time," announces Peter Hook, rescuing his mate, "you don't care where it comes from! You don't even like discussing it or analysing it; you're just glad that it does come. It just doesn't matter where from.

‘Mind you," he beams mischieviously, "I'm not being naive or arty about this. I recognise that this is the only game where someone will ask you 'have you finished that yet?', and you can put your weary head into your hands and whisper ‘no, man, I just haven't been able to get the right vibes yet' knowing that they’ll probably say 'oh, poor lad, that's alright; you’re an artist, I understand.. .' You can get away with all of that, stuff that wouldn't have a hope of washing in the real world."

"Not that we ever do that, mind," Barney hastens to add, “you feel a total c— if you pull that trick..."

Even if we dispense with the comic image of the group's vocalist communicating telepathically with gangs of co-writers, New Order, as a working entity, still cut a pretty unusual dash. We're accustomed to seeing our artists (certainly those who want to be taken seriously and get on The South Bank Show) display some sense of mission or a hintlet that they're somehow driven. New Oder patently fail to demonstrate the slightest sign of either. They are, in fact, for public consumption at least, determinedly lackadaisical.

So how do they work? What ignites the spark? What causes the creative boom?

Another period of silence (contemplative? dumbstruck? bored?) ensues before Barney remembers something: "That creative boom occurs when you're in the studio and it suddenly dawns on you; 'f---in' hell, we haven't got any time left'!"

This is old ground. Barney's always maintained that his lyrics are a last minute rush-job, a panic measure, but it's a bit rich to expect us to believe that the rest of New Order's often dazzling finished product relies on that same haphazard swoop of adrenalin, that it's arrived at without some meshing of talent and graft, inspiration and sweat.

"It involves a lot of work," Peter Hook acknowledges, "real hard work."

"And fear helps too," adds a slightly mournful Barney, "I'm terrified of putting out shit. I’ve said this before, but I thought 'Movement' was a really horrible LP. It really did my head in and I swore I wouldn't let it happen again."

Do New Order harbour other regrets about records they’ve released?

"Yeah." Peter Hook certainly does, "mostly production-wise. I don't think ‘Movement' is a bad record because of the songs, but because of the production. You see, there's always this tension between how you envisage your songs and how they actually come out.

"That was the problem with Martin Hannett and the worst example of it was 'Unknown Pleasures', which bothered me a lot more than ‘Movement’. I had very strong ideas about how it should sound and it ended up completely different from those. Yet everybody thought it was bloody great, which was even more upsetting."

Leaving one bass player with a frustrated, thwarted, ache about a record that many were to come to treasure; a sickener.

“Well yeah, sure, except that I don't remember those songs as ‘the LP’; I remember them how we used to play them, how we envisaged them. Not how Martin made them oome out.

"And it's the same with 'Movement' really. I mean, considering the amount of time and work and stress that was involved, I thought the end product was absolutely diabolical...

“Listening to it was like Ian dying all over again...

The talk somehow meanders around to the people who are ultimately paying for Barney's vendetta with the builders, the people who part with ready cash for their regular fix of New Order. Fans.

Or, in this case, fanatics, because NO are the very archetype of those bands who attract a following of the distinctly hardcore variety. A touch of strangeness, a hint of bolshieness, a constant stepping of a tightrope between glory and a sore arse, an effortless charisma, and an ability to seem to get it right without trying: New Order have all the qualities that combine to elicit devotion.

So much so, I casually remark, that even if the band were suddenly to start issuing rubbish records, they (like, say, David Bowie for a large chunk of the ’80s) would continue to be bought. Hook, jumping astride a favourite hobby horse, takes umbrage:

“I don't believe,” he passionately re-iterates, "that people make 'bad' records, only ones that are more obtuse, or whatever, than others. Come on, someone name me a bad record..."

"Lou Reed’s ‘Metal Machine Music’,” smiles Barney, playing his joker.

“OK, yeah, that was pretty bad,” admits a slightly deflated bassist before regaining his stride, “but there were even people who liked that. Ian Curtis for one. Ian used to really like 'Metal Machine Music’! He played it and he listened to it - it was one of his favourite LPs! Everything’s liked by someone..."

In a lot of cases, aren't committed fans just being bloodyminded?

"But that kind of fannish disappointment,” Stephen Morris takes up the running, "no matter how irrational, is only natural, only human. You mentioned Bowie earlier and he's a case in point. The other day I was listening to ‘Heroes' on the radio and thinking God, that’s soddin' brilliant that; how could he end up doing the horrible Glass Spider tour? What went wrong?"

"And yet,” jumps in Hook, who really should be appointed defence counsel to all under-attack musicians, "I’m sure that tour was the only one on which he did a lot of songs off the ‘Man Who Sold The World' LP, so it was worth it for that alone. On a crap tour he did songs from what was, and is, by his standards, an underground LP - we all gained something.”

Into what has become a rather morbid squabble about the fallability of our idols. Barney suddenly throws a shaft of solid gold common sense:

"The fact is,” he almost whispers, "that no one can be one hundred per cent constantly brilliant. You must f— up sometimes.”

That simple statement ought to be tattooed to the hand of every pop musician, should become an article of true faith. Thus would the vast majority of them be spared the regular humiliation of having to pretend that their new record/tour/video/Woolworths PA is the best thing they’ve ever done, that their creative temperature soars ever higher. And we could relax too, accepting that even our heroes must someday spill egg on their tie.

“I used to believe we had to be incredibly, megacareful about what we put out, absolutely certain about the record. But that just led to my becoming absolutely paranoid about everything, utterly useless. So now I think that you have to just keep on writing and putting it out, even if it’s not completely brilliant. You sort of keep your hand in, knowing that some of what you come up with will, eventually, be brilliant again.”

Just like that. 'Temptation'.,. 'Blue Monday'... 'Thieves Like Us'... 'Love Vigilantes'... 'Perfect Kiss'...

'Touched By The Hand Of God'.. .just like that! The things they don't tell you on Rockschool!

As far as this square-eyed addict’s research can tell, the most widely-exposed rock music on that most rock-hungry of platforms, television, is that of New Order. Various chunks of it have been used to open motoring programmes and science slots, it’s jerked uselessly around behind the test card, and no sequence of BBC sport is now deemed properly attired without its instrumental cloak of NOise. So far it’s backed diving, athletics, rowing, motor sport and, noteably, acres and acres of football.

The band, indeed, made a special edit of 'Thieves Like Us’ - "just the intro looped over and over” - for one Beeb soccer slot, but have exercised little control over the rest of this strange little nether-career. Their response to enforced wedlock to David Coleman varies from Barney’s bullish confidence in the music's ability to "stand up for itself" to the slightly more considered reflections of Stephen. The latter, incidentally, enjoys the advantage of actually having seen some of the broadcasts under discussion:

“So far, I think it’s all fine. Strangely, all the bits that I’ve seen have worked. I'd be bothered if they didn’t sound right or the whole thing looked daft, but up to now that hasn’t been the case. It's quite refreshing to see the music having, y’know, another life...”

But, as so often, the definitive-sounding statement on matters New Order doesn't seem to have been uttered until Peter Hook descends with his tuppence-worth:

“None of this surprises me. The instrumental versions of a lot of our songs are very, very strong, even compared to the same piece with the vocals. With most bands, if you take the vocals off, the music that remains is diabolical. I think that applies very strongly with, for instance, The Smiths' records - take the vocals off and what remains is very ordinary stuff.

“But a lot of New Order’s music is absolutely wonderful, though I say so myself; that’s why you're getting so many people using it to talk over and so on. There's other bands’ music they could use, but, I dunno, to me we're the perfect choice."

With exquisite timing, the background muzak is now treating us to a heinous molestation of U2's ‘Still Haven't Found What I’m Looking For’. Would New Order, snickering now, be as chuffed if they found their precious work being used as the ambient floss in lifts, supermarkets and public toilets?

“I suppose,” Barney sighs, “that you do have to be very cautious with your music so that it doesn’t get cheapened in the way that a lot of classical music has been. The music quickly has no life except that which is associated with Heinz beans or chocolate or drain cleaner or summat. So, yeah, you’ve got to be really, extremely, careful..

“Unless," he titters from beneath unnaturally raised eyebrows, "they offer you enough money!..."

• Next week: ‘Ceremony’ to ‘Fine Time'; New Order on a decade of change, copycats, Manchester, Barry White, their brill new LP and that historic Top Of The Pops appearance...

Comments

Post a Comment