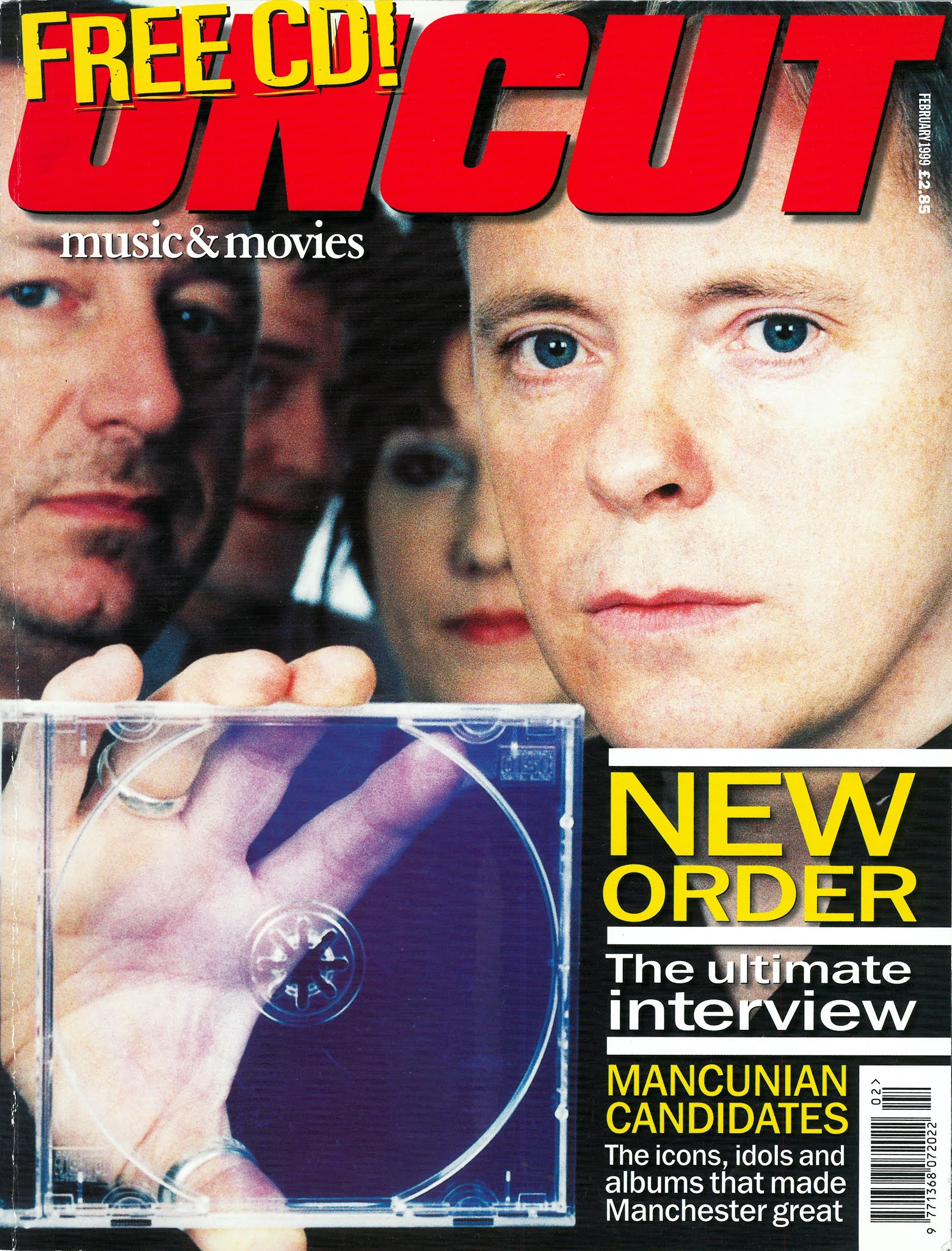

1999 02 Uncut New Order Feature

NEW ORDER formed in the aftermath of lan Curtis’ suicide and the demise of Joy Division, and went on to become the most culturally significant British band of the past 20 years. But their career was always fraught with drug excesses and internal arguments that bordered on open warfare, and they finally split in 1993. For five years, they didn’t even speak to each other. Back together at last, they look back on their years of trauma and achievement in this definitive interview with Paul Lester

AND NOW, FOR THE VERY LAST TIME - JOY Division!" It is July 16, 1998, and Alan Wise local comedian and former manager of Velvet Underground chanteuse Nico - is onstage at the Manchester Apollo, having just hailed the arrival of New Order. Eighteen years, two months and two weeks after Joy Division’s last ever concert, his announcement is, all things considered, both comical and possessed of mythic significance. Would it mean as much to introduce Oasis as The Rain?

Electro pioneer Arthur Baker is here, as is Gary “Mani" Mounfield, formerly of The Stone Roses, now of Primal Scream, as are most of the city's major players of the past 20 years. They have travelled from all over the world, from LA to London, to watch New Order play - to see them actually stand, side by side, in the same place - for the first time since headlining the Reading Festival in 1993, after which the four band members famously stopped communicating for almost half a decade.

Some of Joy Division's gravest hits - “Heart And Soul", “Isolation”, “Love Will Tear Us Apart" and “Atmosphere” - are performed alongside New Order’s greatest hits: “Ceremony", “Temptation", “Blue Monday", “Confusion”, “Bizarre Love Triangle", “True Faith". “Touched By The Hand Of God" and “Regret". Both groups' exalted, extreme machine music is polished to a brilliant shine, all of it suitably remade/remodelled for the penultimate year of the century. “Temptation", in particular, has the brute force and unstoppable momentum of the hardest, fastest big beat or techno you ever heard.

lnevitably, Tony Wilson. erstwhile head of the sadly defunct Factory label (home of Joy Division, then New Order, and Happy Mondays), is at the Apollo, too.

“It is extremely rare for any group or set of musicians who are part of a previous revolution to play any part in the next one - they are always rendered dinosaurs,” he will declare to Uncut six months later, still reeling with excitement from what Manchester's City Life listings magazine hasjust nominated as its Gig Of The Year.

“One of my proudest pieces of art was the NME review of the Hacienda’s 10th birthday party [in 1992],” Wilson continues, as he drives past Manchester's Southern Cemetery, resting place of Martin Hannett, late producer of Joy Division and New Order, “which is the story of Bernard [Sumner] and Gillian [Gilbert] as pied pipers, leading 300 E’d-up scallies through the streets of Amsterdam at four in the morning. It was a most wonderful thing.

“The fact that a group who were so significant in creating postpunk, and then the next thing with ‘Blue Monday’, should be so alive and so much a part of the next explosion - not like some old codgers hanging around, but really intimately involved in it - is a phe nomenal achievement.”

A fortnight after this interview with Factory’s uberFuhrer, artists widely considered to be at the “cutting edge" of dance such as Underworld, Chemical Brothers, Laurent Garnier, Lionrock, Monkey Mafia and Andrew Weatherall will prove him right when they appear at Manchester’s Evening News Arena, and then, two days later, at Alexandra Palace, under the neon banner, Temptation. Top of the bill? New Order, who know a thing or two about dance music themselves.

“They are still children, they are still open to it all,” says Tony Wilson of a group who have been together in one form or another for 23 years, and in that time helped bring the future that little bit closer. A group who were thrown together by the death of a friend, torn apart by what Keith Allen described, with only the faintest trace of a smile, as “bitterness and creeping loathing", in Paul Morley’s 1993 TV documentary neworderstory, and finally reunited, just when everybody thought it was all over, by a fierce mutual respect, even love.

THEY ALMOST CALLED THEMSELVES THE HlT OR THE Witch Doctors Of Zimbabwe. Stevie And The JDs was fairly quickly dismissed, as were Black September, The Eternal and Barney, Stephen And Peter. Even The Sunshine Valley Dance Band, the name of the group formed by 16-year-old ex-acid casualty Stephen Morris, didn't quite make it past the first post when someone suggested it be resurrected.

Instead, they decided upon New Order, either after “the New Order of Kampuchean Liberation" from an article in The Guardian, or from a phrase that manager Rob Gretton had read in a book of Situationist essays entitled Leaving The Twentieth Century. Its Nazi connotations were immediately seized upon by the press - including Private Eye - although the band sidestepped the issue amid ludicrous speculation that they were closet fascists, just as they had three years earlier when they plucked the name Joy Division from the pulp concentration camp novel, House Of Dolls.

And so, on July 29, 1980, 10 weeks after the suicide of Joy Division’s lead singer, Ian Curtis, New Order - billed as “the no-names" because they only found out hours before that they were to replace Belgian group The Names as support to A Certain Ratio and had yet to unveil their new name in public - arrived on the platform that served as a stage at Manchester's tiny 100-capacity Beach Club, by all accounts a cool venue with room for gigs, another for dancing and a third where they showed Andy Warhol films or British arthouse movies like Performance.

“Our mates couldn't make it," began guitarist Bernard Sumner (born Dicken, aka Albrecht) as he approached the microphone, understandably nervous yet somehow relishing the rising panic. “We’re the only surviving members of crawling chaos."

As drummer Stephen Morris points out 18 years down the line, quick to debunk the myth, “Crawling Chaos were a band from Whitley Bay. They were on Factory. We played with them a few times. We had a thing about them."

They had lost their vocalist and lyricist. They were, as Dave McCullough of Sounds wrote, “a band decapitated”. New Order had emerged from the wreckage of Joy Division. Now, here they were, the chaos behind them, reborn, learning to crawl. With macabre wit, Sumner managed to capture the bewildering sense of loss, the sheer drama, the pathos and the poetry, the horror of it all, in one eight-word sentence.

“That’s my dry humour, you see," says Bernard Sumner today. “ It was a sort of comment on the situation. It was, what, two months after Ian had died? I remember we did all instrumentals. That was a pretty good way of ducking out."

Bassist Peter Hook recalls New Order’s live debut rather differently, insisting that all three of them took turns at singing (“I sound like Bernard, even now. We've all got voices the same,” he says. Meanwhile, Stephen Morris was responsible for the vocals on the four-track demo the band recorded three weeks before the Beach Club gig at Sheffield’s Western Works Studios). Although he can’t name the songs they played that night, Hook will never forget how he felt.

“I can't remember what we played because I was too frightened, to be honest with you,” he says. “It was really frightening and you’re really unsure of yourself, so it wasn’t like you were going to enjoy it."

Gillian Gilbert, a friend of Stephen Morris’ (later his girlfriend, since 1994 his wife), was one of the hundred or so people down at the Beach Club. A student of graphic design at Stockport Technical College, a member of all-girl group The Inadequates and a Joy Division fan of long standing, within two months she would be invited by manager Rob Gretton to join the band as second guitarist and keyboard player. New Order's soon-to become fourth member noted the excitement of the crowd as soon as they realised who was onstage.

“It must have been weird playing a gig like that in Manchester." says Gillian. “They looked very strange being cut down to a three-piece. after seeing Joy Division, and then seeing this weird little triangle.

“It was all eyes. People were just staring, waiting for something."

They were waiting, specifically, to see what the three pale, young men onstage were capable of, to hear how their music - reworkings of “Ceremony” and “In A Lonely Place”, written by Ian Curtis two weeks before he hanged himself, plus tentative versions of “Dreams Never End", “Truth" and a few other electronically enhanced pieces that would later wind up on New Order’s debut album, Movement - would develop over the course of the evening. Perhaps they were also waiting, with voyeuristic intent, for the latest installment in rock’s Atrocity Exhibition.

For three years, they had waited - outside concert halls and record stores - for “the last British band,"

according to Uncut’s David Stubbs, “who truly mattered, for whom something was truly the matter.”

Now they were waiting for a group that might replace Joy Division.

They got New Order. They would not be disappointed.

GIVING UP IN THE WAKE OF IAN Curtis' death wasn't an option. As Stephen Morris puts it, “We never had any big discussions about it. We just got on with it.” Bernard Sumner confirms that they already had “Ceremony” and “In A Lonely Place” - the songs that would form New Order’s first single release, in March, 1981 - under their belts; after that, it was just a question of building on these very fragile foundations.

“We had written the backing tracks while Ian was in some sort of psychiatric hospital after he’d tried to commit suicide," says Sumner of Curtis’ attempt to overdose on Phenobarbitone on April 7, 1980. "And we, rather than sitting at home and panicking, decided to carry on rehearsing. So we wrote ‘Ceremony’ and ‘in A Lonely Place“ while Ian was having treatment. And then, when he came to the next rehearsal, we presented him with these songs. and he said. ‘All right. I've got some lyrics.’

"We wrote them in this horrible rehearsal room they used to have in Salford. There were rats - very suited to the music of Joy Division: they complemented the weird atmosphere. Anyway, we wrote the songs and Ian added the words, and we had this really shitty tape recorder, so after going through each song once, he went away. And he died that weekend. So the first job we had as New Order was to take this horrible garbled tape and put it through a graphic equaliser and try to decipher what words he was singing."

The words Ian Curtis was singing - on the funereal “In A Lonely Place“ - were these: “Hangman looks round as he waits/Cord stretches tight, then it breaks/Some day we will die in your dreams/How I wish we were here with you now."

“That was a very shocking line to hear after he's hanged himself," says Bernard Sumner. When asked whether he was concerned about the fidelity of his interpretation of Curtis’ original lyric, he replies: “I think they were pretty accurate. I am sure there are one or two phrases which he's probably spinning in his coffin over. But that serves him fucking right for killing himself. He put us through it.” He laughs. Then, more seriously: “Afterwards, I listened deeply to what he was singing, and I just thought, ‘What a heavy set of lyrics for someone at the age of 23.’ They seemed to me to be the words of a much older man.

“I didn’t really go back and listen to those [Joy Division] records until probably a year later because, obviously, it was too emotionally painful - he was a dear, dear friend of all the group and we were all very close. But it was also annoying that we had done all this work for seemingly no reason. This is unspoken but, to be honest, I think we all felt a bit angry that we had just been pawns in his play.

“We all felt a bit powerless. We had all given up our various day jobs and there was nothing else to go back to. I know it sounds very mundane and down to earth, but the reality is that we had to pay the rent. We had been on the verge of mega success when it happened and we were like, ‘What are we going to do now?'.

“I think ‘horrible’ is the expression that comes to mind," Sumner glances over his shoulder at that Beach Club gig. “it was an ordeal. It was like going to the local municipal swimming baths having just had your left arm amputated, and trying to swim. Literally painful. And thinking, ‘Fucking hell, it was better before when I had another arm.’

===========================

INSET:

MOVEMENT (1981)

The difficult first album. You could almost smell the fear. Listeners immediately solved the acronym on side two, “ICB”: Ian Curtis Buried.

Peter Hook sang the comparatively upbeat “Dreams Never End” while “Doubts Even Here” had the bassist on vocals with Gillian Gilbert providing the enigmatic voiceover. “The Him" jolted from stark proto-electro to furious thrash. “Truth” featured a melodica and ectoplasmic synth.

“Senses” was an overlooked exercise in ghostly stereo-panning interrupted by the noise of shattering glass.

“Denial” was oppressive yet strangely, arhythmically, danceable. An unjustly maligned return literally - from the dead.

Gillian Gilbert: “Everybody had a lot of ideas."

Stephen Morris: “There was a bit of an atmosphere. We were just finding our feet again. Some of the songs are not quite there.”

Peter Hook: “I think they’re all really good songs. A very good album.”

Bernard Sumner: “It was kind of nervous writing, really. I hate those songs. We recorded them, I played the album once, and I don’t think I ever played it again. In fact, I don’t own a copy."

===========================

"I thought Joy Division were a great group, and Ian was a great performer and a great lyricist, and the chances of getting anywhere near that again must be pretty remote, so you felt very much like you were heading towards a precipice. Personally, I thought 'Fuck it, my life is going to turn into a dive bomb and go into a steep dive, then I'm going to make sure I have a fucking great time when it happens."

"But it never crossed my mind to give up. There was no question. Although the odds didn't look good."

New Order faced more difficulties during their first mini-tour of America - the very tour on which Ian Curtis and Joy Division were due to embark on Monday, May 19, the day after he killed himself. The dates were postponed until the end of September, and included Maxwell's in Hoboken, New Jersey, and Hurrah's in NYC. On the Tuesday night, between the Maxwell's and Hurrah's dates, their rented van containing nearly $50,000 worth of uninsured equipment (which had been left unlocked and unalarmed because the band's roadies were apparently too involved in a petty dispute) was stolen by a gang operating under the name of The Lost Tribe Of lsrael, who, explains Stephen Morris, ‘specialised in nicking English bands' gear”. They spent the next day frantically buying and renting instruments and amplifiers.

The portents were not good for New Order's first Stateside trip. As Peter Hook recalls at the studio based near his home in Didsbury, a suburb of Manchester, “it wasn't really very enjoyable. We were trying to find our feet. We were still very young.“ To Stephen Morris, speaking to Uncut at the farm house (with built-in studio) he shares with Gillian Gilbert in Macclesfield, they were, "basically, just getting on with it."

As for Bernard Sumner, interviewed for this article at his modern-style residence close to Alderley Edge, 15 miles south of Manchester, he had already been prepared for the worst. "l remember having a horrible dream the night before [we left]." he says. “We were going over on a 747 and helping them to put a coffin on the plane. It was pretty traumatic."

But then something really unexpected, strange even, happened. Despite, or maybe because of, the stress and the problems they were facing, New Order rediscovered something that had been lost since Joy Division's heyday, before Ian Curtis‘ epilepsy, his physical and emotional breakdown, his suicidal tendencies, planted a bomb inside the band: the art of partying,

“We realised what a great fucking party town New York was," says Bernard. “We started going to all the clubs, like Danceteria, Hurrah’s, the Peppermmt Lounge. There was a lot of rapping." They even took the loss of their equipment in their stride, as Sumner recounts. “The plan was that Martin Hannett would come over and we would go into this studio in New Jersey after a few days of living it up. So we recorded ‘Ceremony’ and ‘ln A Lonely Place’ and that was kind of traumatic because l was doing the vocals - I think we all had a go, but I ended up doing it. It felt odd.

“Then we had our first taste of ‘poppers' [amyi nitrate, a powerful stimulant] when one of our roadies came in the studio and said, ‘Get your nose on this, Smell it.’ l had a big snort of it and it nearly blew my fucking head off. They [the 'poppers'] made us laugh and go bright red. And working with Martin . . . he was a fucking party monster as well. Anything he could lay his hands on. He loved it out there.

“We were staying in this horrible hotel. Me, Hooky and Rob [Gretton] were all sleeping in the same room, like the three bears. I remember Tony Wilson coming into the room and waking the three bears up. He just started laughing. ‘You’ll never guess what happened.‘ And we said, ‘What?’ And he said, ‘You've had the fucking van nicked with all the gear in,’ and pissed himself laughing.

“So we all went down to the police station en masse, this American Precinct 13 or whatever it was, and there was this copper with a big ghetto blaster playing ‘Good Times’ by Chic, and he was dancing to it, and we'd just had $47,000 worth of equipment stolen, and he turned round to us and said, ‘You’ll wait until the fucking record finishes.’ So I’ve got this less than endearing memory of ‘Good Times’ by Chic.

“I remember later on going into this shop and it looked to me, the naive Englishman, like a tobacconist’s, and l thought, “Right, I’m here in New York, parched with thirst, it’s 100 degrees outside, I’ll go into this tobacconist's and get a can of Coke.’ So I went in and said, ‘Excuse me, do you sell Coke?’ And he said, ‘No, sir. we only sell the kits for freebasing.‘ And I said, ‘No. Coca-Cola.’ He went, ‘Get out of here, man.’"

BACK IN BRlTAlN THAT OCTOBER, NEW ORDER, AT the behest of Rob Gretton, decided to draft in a fourth member: Gillian Gilbert, a friend of Stephen Morris' younger sister, Amanda, who had known the band since their days as Warsaw. Although quite accomplished on guitar and synthesiser, Gilbert was picked, first and foremost, because they all knew her (as Sumner told me, “It’s always been based on friendship, not musicianship”), but also because they liked the fact that she did not have a developed, recognisable or incompatible musical style.

Gillian’s arrival freed Sumner up sufficiently for him to start handling vocal chores, which was just as well since he “couldn’t play and sing at the same time". Considers Morris, “there was no way we were ever going to replace Ian. We thought about getting another singer” - Alan Hempsall from Factory's Crispy Ambulance was in the frame - “but it just wasn’t right." Gilbert admits to feeling nervous on day one, “especially when you’re learning to play songs they’ve already written. But I didn’t have any expectations so I didn’t feel that frightened. I was sort of cocooned. And I liked the music, so I just got on with it.”

Peter Hook, who was “over the moon” all throughout Joy Division, has painful memories of this period of transition leading up to the recording of Movement.

“I wouldn’t say we gelled straight away,” he admits. “It was really difficult because everybody was changing. Put it this way: it wasn’t like I’d get up in the morning and go, ‘Wow, this is great being in New Order.’ It was too difficult.

“Why? Because of the death of Ian and all of us jockeying for position, and not knowing who wanted to do what. It was a big change, a big upheaval. I don’t think you ever felt comfortable with it. And Gillian came in and she couldn’t play, and it wasn’t like she was coming in saying, ‘Right, well, how about trying this or that?’ She was more or less just sitting there being told what to do. It didn’t make it any easier for us.

"If anything,” he concedes, “it was nice because you didn’t have somebody changing the way you did things. But you very much had to teach her. I’m sure she wouldn’t dispute that. ” Did the band not feel liberated, musically, by their new recruit? “You don’t have the freedom to do what you want in a group. Being in a group and having the freedom to do what you want don’t go together. I’m sure you must know that.

“It was Rob’s vision of the group and his moulding of it. It was his idea to get Gillian in. And it went from being a very laddish band to having a girl, which made it different, which you sort of resented for a bit - or I did, anyway, because it spoiled my fun, which is a very stupid attitude, but that’s just what it is. You had to cope with that. You had to cope with the death of Ian. You had to cope with the fact that you weren’t making music nearly as easily or as confidently as you used to.

"You know, you’re used to walking onstage with Joy Division, and you’d be proud as punch. It’s like, ‘Yes! Come on, you bastards! We’re gonna give it yer!’ And you go on as New Order and,” Hook adopts the voice and stance of a scared little boy, “it’s like, ‘Oh my God, what’s going to happen tonight?’ To lose that and go to that was pretty fucking traumatic. It was like crawling your way up a slippery slope. And then, lo and behold, eight or nine years later you’re fucking back there and you can go, ‘Yes, you bastards - have this!”’

This, explains Hook, might account for his reputation for surliness and aggressiveness.

“Those bits where you had your back to the camera,” he says, and as usual when he speaks, for “you" read "I", for “your” read “my". “When you look at the videos of me playing with my back to everybody, just fucking playing, not moving, and four years later you’re there, thrusting your groin in their face, well, I’m sure if you showed that to a psychologist he could quite easily interpret it. It's about getting your confidence back. When you feel insecure, you tend to lash out, you hurt people, whether they deserve it or not.

"Regrets? No more than anyone else. Everyone was an arsehole. Everybody knows the score. Nobody was God. Everybody has their own little niggles, did things wrong, bullied, cajoled, was very selfish. Everybody did it.”

AFTER THE SEX PISTOLS AND THE CLASH, THERE were two bands - two bands without whom the late Seventies/early Eighties would have been quite different: Joy Division and The Jam. Each, in their own way, attracted a ferociously loyal, devout following, though to belong to both camps was highly unlikely. They were as dissimilar as England’s North and South.

Joy Division, more than The Jam, more than anyone, with their icily imperious though sonically exploratory rock and Ian Curtis’ poetic anguish, seemed to inspire all manner of intense emotions. Consider the feelings aroused today by groups like Nirvana, the Manic Street Preachers and Radiohead, only raised to fever pitch. “Love Will Tear Us Apart” was the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” of its day; “Atmosphere” the "Everything Must Go”; “She’s Lost Control” the “Subterranean

Homesick Alien".

“There was a dark, cold, terrible, authentic centre to Joy Division which exists in no other rock band,

European or American, past or present," as David Stubbs wrote in Uncut's review of the Heart And Soul boxed set last winter. Then the singer dies, the remaining members regroup, and then - as far as the London media who had canonised Curtis (Dave McCullough’s notorious “this man died for you” was typical) are concerned - nothing.

Remember: in rock history, no other band has managed to survive the death of a crucial member; only Pink Floyd have sustained a career well beyond the departure of their singer-songwriter.

So you can imagine the sense of anticipation when New Order finally played their first date in the capital in February, 1981 (“The Haunting Of Heaven" was the title of Paul Morley’s NME review of New Order at Heaven in Charing Cross, where many of the audience were close to tears). What’s harder to imagine is how it must have felt for New Order to have the crushing weight of a nation’s expectations on their shoulders when they plugged in to perform live, or in the studio.

If anything, what startled about New Order’s debut single, “Ceremony” (backed with “In A Lonely Place ’, and with a sleeve design, all ecclesiastical typeface and solemn ambience, courtesy of Peter Saville - along with Rob Gretton, Joy Division’s unofficial fifth member), released in March, 1981 - the first new recording from Sumner, Hook and Morris since Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart” the summer before—was the weightlessness of the production and the uplifting quality of the song. A little light had been shed upon New Order’s art of darkness. That “Ceremony" sold 100,000 copies within two weeks was less surprising.

But with all that had gone before, and with all the changes they were experiencing, it was no wonder that New Order found it difficult to get to grips with the recording of their first longplayer, which they worked on throughout 1981, again with Martin Hannett at the controls.

“It was really difficult - for Martin more than anyone," says Stephen Morris of producer Hannett, who was particularly badly affected by Curtis’ untimely death. “I think he wanted us to do more, and we wanted him to do more. He was turning up late. It was a bit of an ordeal for him."

"Movement was very painful, for thousands of reasons,” says Peter Hook. "Hannett was off his head,

which didn't make things any easier, it was 'Ceremony' [not on Movement] which decided that Bernard was going to sing. It was going to be me and Steve, and then Bernard begged for another go. Not that it bothered me. Whatever. But Martin was so fucking fed up. I think it’s a very good album. Bernard and I wanted it to be much rockier, whereas Martin went for the more 'gothic'-type wimp-out feel. We were still learning."

Continues Sumner: "I shouldn't speak ill of the dead, but I always felt that, after Martin got his hands on it [Movement], it was even worse. I think he was very broken up by Ian's death. But he was also a complete fucking drug monster, and he was well into smack at that point, so he kept disappearing, or he would be extremely restless. I'm not saying it’s his fault - it wasn't.

“You know, a lot of people say depression is a good trigger for writing, but for us, I don’t think it was. It was funny, really. The music of Joy Division is very down and depressed, but we were very up in Joy Division, very into having a good time, having fun. But around the time of Movement, I just couldn’t write anything. I felt like the flame had burnt out.”

IF MOVEMENT WAS OVERBURDENED BY EVENTS FROM New Order's past, it did contain the seeds for their future. There, on side one’s closing track, "Chosen Time", was everything New Order would need to start their electronic pop revolution: the crude yet exhilarating metronomic pulse chased along by a liquid baseline, the jagged guitar pattern illuminated by shades of synth, some pre-Acid squelches, and mood-shattering Moog FX.

Joy Division's Year Zero was 1976/7: the birth of punk, but also the dawn of the digi-pop age. Ian Curtis would regularly turn up to recording sessions with Kraftwerk albums under his arm, while his love of Iggy Pop's Bowie-produced The Idiot - with its slow but relentless "motorik"beat - is well documented (he was listening to it the night he died). During the recording of "Love Will Tear Us Apart” the band would listen to Sparks' “Number One Song In Heaven”, a collaboration with Giorgio Moroder (whose E=MC2 solo album became a huge inspiration). Joy Division's “As You Said’ (B-side of the “Komakino" flexidisc) was a trans-European homage to Kraftwerk, while the 12-inch mix of “She's Lost Control” features a crisp and pristine piston hiss-rhythm that is quite astonishing for its time (July, 1979).

Bernard Sumner had built his first synthesiser while in Joy Division from a kit, learning about circuitry and components from manuals. As the Eighties began, he developed an interest in the robo-melodies of the Munich-based Moroder (co-writer of Donna Summer's “I Feel Love", arguably a more useful 1977 benchmark than The Sex Pistols' “God Save The Queen’), as well as in early Italian disco and Chic's urban symphonies.

Meanwhile, over in Sheffield, Cabaret Voltaire (who had appeared alongside New Order at Hacienda precursor. The Factory Club, and Sumner believes “were probably more pioneers than us") were experimenting with analogue tape (an early form of sampling) and sequencers, and The Human League were hatching their plans for global synthesiser domination. New Order - as they would for the duration of the decade - had their aerial antennae up. They were picking up on what was happening, from Dusseldorf to New York to South Yorkshire

Bernard Sumner had built his first synthesiser while in Joy Division from a kit, learning about circuitry and components from manuals. As the Eighties began, he developed an interest in the robo-melodies of the Munich-based Moroder (co-writer of Donna Summer's “I Feel Love", arguably a more useful 1977 benchmark than The Sex Pistols' “God Save The Queen’), as well as in early Italian disco and Chic's urban symphonies.

Meanwhile, over in Sheffield, Cabaret Voltaire (who had appeared alongside New Order at Hacienda precursor. The Factory Club, and Sumner believes “were probably more pioneers than us") were experimenting with analogue tape (an early form of sampling) and sequencers, and The Human League were hatching their plans for global synthesiser domination. New Order - as they would for the duration of the decade - had their aerial antennae up. They were picking up on what was happening, from Dusseldorf to New York to South Yorkshire

They just knew the future should be synthesized.

“It was Bernard," says Peter Hook, “his love of experimenting with electronics. It’s like he’s always looking for something else ... he had so much of it, he was like a kid at Christmas. Spoilt for choice. He wanted to get into that dancey thing that Ian had introduced him to - that Kraftwerk, machine-type beat.

“I think what Bernard really wanted,” he hints at some of the darker urges pushing the band forward,

"was to be able to write without talking to us. He wanted to write drums without having to talk to a drummer and he wanted to be able to write bass parts without talking to the bass player. As technology moved on, he achieved that.

“There was a lot of being written out. It was quite easy to write me out. I’d be playing acoustic and he’d be trying to programme sequencers. And I’d come up with something and he’d go, ‘Can you hang on a minute, I've just got to programme this little bit here, can you just wait?’ And then sometimes it would sound like what you’d been playing, and other times exactly like something else. But then he’d go, ‘Oh, we don’t need that bit there because we’ve got this bit on the keyboards.’

“It’s quite easy to be written out. It’s just taste, isn’t it? It’s the way taste evolves. His taste changed. He didn’t like writing in the group format. It’s only taste; it’s not personal.

“I wrote keyboard lines for ‘Confusion’, I wrote Touched By The Hand Of God’, I wrote ‘Death Rattle’, so I do write keyboards, but it isn’t my love, it isn’t my lust. My lust in music is playing bass guitar. When I get a shit-hot bassline, that’s what makes me happy. I can do keyboard lines till they're coming out of my arse; I'm not interested in them.

“I think Bernard felt very frustrated by my resistance to change, and the more he wanted me to change, ” says Hook, imagining himself back in the studio in 1981/2, confronting a gadget-hungry Sumner, “the less I was going to fuckin’ change, right?’

New Order's frictional relationship produced groundbreaking music, and great art. Following an appearance at that summer’s Glastonbury festival - which saw Bernard Sumner, nervous at having to sing before such a huge audience, literally keel over and collapse onstage, blind drunk - the band released “Everything's Gone Green’’.

Originally the B-side of second sing|e "Procession” in September, 1981, the track had a far greater

impact when it mysteriously reappeared on 12-inch on Factory’s Belgian imprint, Factory Benelux,

three months later. Extended to almost six minutes, “Everything's Gone Green” was, as Stephen and

Gillian explain, the result of Martin Hannett finally setting his proteges free: he set the band up with the right equipment, then stood back and watched them go. Sumner mixed it. “Martin was happy with that," says Morris.

"Everything’s Gone Green’ was the first step in the new direction,” agrees Bernard, who employed a "boffin guy, like a top scientist, a real genius” called Martin Usher to design circuit diagrams and generally help New Order realise their electric dreams. Usher, “an old hippy”, was rewarded for his efforts with tabs of acid.

===========================

INSET:

POWER, CORRUPTION & LIES (1983)

Then there was light. Featured alternative “Blue Monday" in “586”, the trad-NO sound of “Leave Me Alone" (formerly “Only The Lonely"), the atonal “Ultraviolence” (a nod to A Clockwork Orange), the heavily-vocodered “Ecstasy" and the - no other word - jaunty "The Village”. The studio name for track one, side two - "Your Silent Face" - was “KW1”, ie, "the Kraftwerk One", a homage to the Germans whom Sumner believed epitomised everything he wanted pop to be: “rhythmic, abstract, aesthetic, arty, fucked-up and with a sense of humour.” The lyric bore this out: "You’ve caught me at a bad time/So why don't you piss off?"

Bernard Sumner: "I like dropping bombshells in my lyrics. You can't be serious and weighty all the

time. We are all deeply shallow people."

Stephen Morris: "The lyrics said what we wanted to say."

Gillian Gilbert: “What could we say? ‘Wrong direction, darling'? ‘Well, you come up with something better, then!’”

===========================

“We didn’t own any sequencers,” furthers Sumner, “but I’d heard some going to clubs - music done with tape loops like disco, where they’d looped the drums, the way people now use samplers. I found the precision very interesting. That was what I really wanted to do: find a new kind of music.”

Using a variety of modified gadgetry and customised, purpose-built synths which allowed Gillian’s

keyboards to pick up electronic pulses from Stephen’s drum machines or Pete’s bass, they were able to trigger mechanically precise rhythms or sequence patterns from each member’s instrument.

“We just made it up as we went along," posits Gilbert. “I suppose it was kind of state of the art,"

grants her husband. “It didn’t get any flashier at the time.”

"Temptation” (performed as "Taboo Number 7” on BBC2’s Riverside in January 1982) evinced New Order’s rapidly advancing techniques, and was their first experiment with digital recording. Their most popular song to date, too: released in June, the 33rpm seven-inch of “Temptation" b/w "Hurt” (with its equally perverse, impossible-to-decipher Peter Saville sleeve) reached the Top 30.

They weren’t just experimenting with electronics, though. There was some chemical exploration

going on as well. Bernard’s lyric ("Up, down, turn around, please don't let me hit the ground... Oh,

you’ve got green eyes, oh, you've got blue eyes, oh, you've got grey eyes”) was about as far removed

from the dolorous introspection of Movement as it was possible to get without the aid of pharmaceuticals. Actually, it was achieved with the aid of pharmaceuticals.

“I was on acid when I recorded the vocal to ‘Temptation’," he says, revealing that it was virtually

improvised on the spot, part of the reluctant lyricist’s policy of “freaking out my conscious mind to send a signal to my subconscious” to galvanise his brain into summoning forth words of wisdom - or, in the case of “Temptation”, a vision of romantic love seen through a psychedelic prism.

“I just made ft up in the studio,” he recalls New Order’s burgeoning sense of adventure - and fun. “I’d

been doing acid all night with a mate over in Blackpool. Not organic stuff, no - tabs. I was actually on acid when I sang it. I remember we were in this studio called Advision near the Telecom tower in London, and it started snowing, and we looked out the glass windows, and if you listen to it carefully you can hear Rob Gretton come in while I’m doing the vocal and shove a snowball down the back of my shirt. We kept it on the record.

“He was tripping off his box. We were all tripping."

THEN THEY RECORDED THE BIGGEST-SELLING 12-inch single of all time.

“Blue Monday” is an accountant’s dream and a statistician’s nightmare. It has sold three million copies worldwide. Since records began in 1952, only five acts have spent longer on the charts than New Order’s 52-week run with their fifth single (for the record, they are: Frank Sinatra with “My Way”, Judy Collins’ “Amazing Grace”, Bill Haley’s “Rock Around The Clock”, Englebert Humperdinck’s “Release Me” and Acker Bilk’s “Stranger On The Shore”. Frankie Goes To

Hollywood’s “Relax” ties with “Blue Monday”).

It reached Number 12 in the UK Top 30 in March 1983, re-entered at Number 9 in August after it

became the summer’s Eurodisco anthem, peaked as high as Number 3 when Quincy Thriller Jones reworked it in the capacity of “production supervisor” in 1988, and stalled at Number 17 after being overhauled for a third time in 1995.

There had been electro-pop records before, and “club culture” - essentially, the white British media, having got bored with rock, picking up on black music, its attendant nightlife and lifestyle - had been a buzz-phrase since 1981. But “Blue Monday” was arguably the first point of access to this strange new world of pleasure for the general public.

Overnight, New Order acquired a massive fanbase, including, not just Joy Division’s stereotypical great-coat-clad student miserabilists (“Thank God,” says Stephen Morris), but high-street fashion victims, secretaries and football thugs. “Blue Monday” was credited as the first true crossover record since “Anarchy In The UK”, the one that rebuilt the musical landscape shattered into numerous tiny fragments (genres) by punk. It probably inspired a thousand bedsit technocrats to buy some cheap equipment and create their own DIY dance as well. And if you want to locate the source of 1988's Second Summer Of Love, that shortlived Ecstasy-fuelled Utopia where "luv’d-up" casuals and college kids surrendered to the machine delirium, look no further than “Blue Monday”.

Typically intransigent and wilful, they performed it live - unheard of at the time - on Top Of The Pops and The Human League and U2’s Bono (who would later pay tribute to the band on neworderstory) came over afterwards to apologise for miming. Neil Tennant, former editor of Smash Hits and, later, one half of the Pet Shop Boys, broke down in tears when he heard “Blue Monday" and saw the sleeve's facsimile of a computer floppy disc. This was exactly the future he and partner Chris Lowe had envisioned. How dare New Order beat him to it?

Fairly impressive for a song that evolved out of a comical misunderstanding between Bernard Sumner and Stephen Morris.

“It’s meant to go, ‘De de de.'”

“‘De de de’?”

“No, ‘De de de.’”

“‘De de de’?”

“No, that’s not it. But it’ll do."

“How does it feel, to treat me like you do?" A masterpiece of impromptu invention, “Blue Monday" was, maintains Sumner, a riposte to critics who had, as he saw it, callously dismissed their debut.

“The press had turned on us by that point. The sympathy angle had gone and they were sticking the knife in and twisting it. It was our ‘fuck you’ to them. Movement hadn’t been very well received and that personally made me a bit angry. I thought we should have been given a bit of breathing space. Not only had we had this great catastrophe, but now all the - no offence - parasites had turned on us.”

If New Order had their detractors in the music press, they were few and far between. From “Blue Monday" onwards, the band were regarded with almost religious awe, each of their releases seen as signposts for pop's future. “Confusion”, the next single, was produced by Arthur Baker, the Manhattan-based technician responsible for the slice of Teutonic Americana - the Rap goes to the Rhineland of Afrika Bambaataa And The Soul Sonic Force’s “Planet Rock” from 1982 -that spawned an entire movement.

The result of Baker locking the four in the studio and forcing them to write a track on the spot,

“Confusion” was effortlessly contemporary. Journalists were fascinated by New Order's absorption of the aesthetics of dance, sending eyewitness reports home from the States of the band dressed in casual beachwear - shorts, T-shirts, sneakers - as they flitted from one hi-tech danceteria to another. They were especially intrigued by Puerto Rican hip hop joints like The Funhouse, where local

breakdancers would contort their bodies to the latest streetbeat: the mutation of rap into electro. Although it would prove crippling and contribute to escalating tensions within the band later on, New Order's financial support for Manchester’s Hacienda - that dazzling example of industrial futurism which opened in June, 1982 - emphasised their commitment to, and synonymlty with, the new club culture.

THEIR SECOND LONGPLAYER, Power. Corruption & Lies, featured a still-life of some roses on the front by Henri Fantin-Latour and another faux-floppy disc design on the rear. Subdued, anonymous (minimal information, no band photos) and stylish. Simple yet sophisticated. Arty,

Intelligent. Modern. Released in May, 1983 it was actually recorded five months earlier. Provisionally

titled, variously, Fuck, Piss Off You Lot and How Does It Feel?, those sessions down at Pink Floyd’s

Britannia Row studios were unusual to say the least.

For a start, it was, as Stephen Morris recalls, “bleedin' freezing", which meant the band had to wear

overcoats in the studio. Or rather, Morris, Peter Hook and Gillian Gilbert wore overcoats. Bernard

Sumner’s choice for bodywarming outerwear was a white lab coat, as worn by nuclear scientists. That wasn’t all. On one bizarre occasion, the increasingly mercurial, wayward Sumner decided, for some unfathomable reason, to purchase the soul of their soundmixer, programmer and tour manager, Andy Robinson.

Then Bernard unveiled a brand new method of getting connected to his muse and generating lyrics: picking up New Order fans' thoughts and dreams about the group by way of an invisible radar system wired up to his brain and converting them into songwords. Oh, and the taskmaster had, as far as Stephen and Gillian can remember, taken to lashing his three bandmates with a stick.

“It was this woodcracking thing, they both laugh, “There he was in his white coat, holding a stick with a sort of belt attached. ‘Oh, you bastard. Ow!’ That had us in stitches. ”

Self-produced for the first time, Power, Corruption & Lies was different to Movement - almost the sound of a different band. Exuberant. Confident. Audacious. Joyous, even. The sound of a band coming to terms with their past and fired up by all the possibilities - technological, instrumental, emotional - before them. Power, Corruption & Lies offered a seamless blend of the acoustic and the automated, the real and the virtual, where computer wires and guitar strings were afforded equal priority.

Whatever had been going down between the four musicians in the studio - and, like any band, there

were disagreements, points of disorder, moments where the proverbial creative differences gave away to genuine discontent - to the listener it was the soul a band high on life.

It was also the sound of a band pumped full of drugs.

“That was the influence of a certain Mr A M Phetamine," says a droll Morris, referring in particular

to Sumner's frenetic rhythm guitar playing on opening track “Age Of Consent” that would become as much a signal New Order sound as Peter Hook’s plaintive topend bass notes, Stephen Morris' immaculate clatter and Gillian Gilbert’s overwhelming waves of synth.

Sumner backs up Morris’ account, although he recalls a different stimulant being at hand during recording.

“We were out of our heads on acid the whole fucking time," he says, although, for the sake of accuracy, Stephen was strictly on alcohol (Pernod and Asti Spumante cocktails were a band favourite) since, as he told me, “I’d done all that [ie, acid] when l was 12.”

Bernard will not be swayed, however. “We used to do it every single day. Not enough to give you hallucinations. A full block would give you hallucinations, but just a bit would be enough to give you a change of perspective. We'd get a razor blade and cut off a little slice every day. That’s when we wrote ‘Ecstasy’ [the penultimate track on the LP], which is funny because, when people got into E later, they wrote tracks about acid.

"It was very much an experimental thing,” he goes on. “We’ve found something new and interesting, let's experiment with our psyches, let's experiment with this new form of music, let’s experiment with all these drugs.’ We realised it was more fun to be up all night when you were off it than to be up all night when you weren’t. It was just basic need, really."

Sumner lays the blame for this quirky new regime at the door of their former mentor. “ It was Martin Hannett’s fault. He’d got us into this thing where you'd arrive at the studio at about five pm, lock the studio door, wait until the staff had gone, and then get as fucked-up as possible and see what the end result was the day after. That kind of mentality carried over when we started producing ourselves.

Although Peter Hook says he has “no reservations" about the music they were making - and he describes Power, Corruption & Lies as the last album that they actually “sat down and worked on together, until it was finished; we used to write together a lot more then” he does have mixed feelings about the period as a whole, the problems within the group, with Factory Records and the Hacienda, all of which were bound up together in one potentially explosive package.

On the one hand, they were “having fun, going out partying all the time”. On the other, there was Sumner’s emergent facility with the new technology, which tended to ostracise the rest of the band.

“He was wearing his white lab coat; he used to go into his other persona. Bernard likes, or he used to like, to write on his own. I think he used to feel that everyone

===========================

INSET:

LOW-LIFE (1985)

Gruelling 36-hour recording sessions yielded album of fabulous electro love/hate songs. Title swiped from Spectator columnist Jeffrey Bernard, who sued for the removal of his voice on “This Time Of Night”. Their first album to feature the band on the (tracing paper-effect) sleeve (Morris: “What was it trying to say? ‘Hey, this is what we look like.’”). Contained actual single releases: “Sub-Culture” (“One of these days when you sit by yourself/You’ll realise you can ’t shaft without someone else") and “The Perfect Kiss”, the latter either a revenge fantasy, an AIDS parable or a celebration of masturbation (“Tonight I should have stayed at home/Playing with my pleasure zone"). Love Vigilantes” was, of all things, a country’n’techno song about a Vietnam soldier returning home to his wife.

Bernard Sumner: “It was a pastiche; a pisstake. People are so pious about lyrics. The first single I ever bought was ‘Ride A White Swan’ by T-Rex. Absolute gibberish. But I didn't give a fuck. Bow down before the tune. The tune is God.”

===========================

Hook was frustrated by the fixed roles of the New Order players. “It was like, “We're in a group, right, that's it, we don't do anything else. That's what we do. We're punky. No, I play the bass. You fuckin' shut up and play the guitar, c* ** .' It was like that.

“It was always very difficult. It was prejudiced by Rob's attitude to the group and Factory. It was prejudice by Rob's involvement in Factory. It was prejudiced by everybody being unhappy with each other, the business side of it. The Hacienda was crippling you, Dry [the Manchester city centre bar New Order acquired, and had a stake in, later on] was crippling you. It made you not want to see people."

Hook is keen to stress that he is “only talking from my point of view. The others might have enjoyed it immensely," adding: ”Basically, we had a big falling out because I didn't like the way he [Sumner] was changing, which is a purely selfish attitude, I know. Musically or personally? Both. I mean, there’s a lot of stress and strain. You don't realise how much fucking pressure singing is until you do it yourself [Hook provided the vocals for two Movement tracks and, later on, sang with Revenge and Monaco].

“But then, unfortunately, it's too bleedin’ late. You can’t go back and say, ‘Sorry about that 15 years of being a twat, I’ve only just realised what it’s like.' It's like realising what your mother or father did for you 15 years later. It comes to you and it's like, ‘Oh, my God, I’ve been a complete arsehole and it’s too late.'”

POWER, CORRUPTION & LIES ENTERED THE ALBUM charts at Number Four. “Confusion” reached Number 12 in September. The band toured Australia, New Zealand and Japan (where the technophile Stephen Morris was singled out for special attention). They were huge across Europe and had an enormous cult following in the States. Over the next few years, via a series of increasingly successful records, they would find themselves, simply, the biggest independent band the world had ever seen. The more they eschewed conventional music business practices (no record company promotion or advertising; non-album tracks as singles; a nonexistent “image"; few, if any, interviews; refusing to leave Manchester for the capital), the more popular they became.

When they began as Joy Division, their peers were the Pistols and The Clash, then Public Image Limited and Wire. In the early days of New Order, they were part of - yet remained supremely aloof from - a scene that included the likes of ABC and Heaven 17. By the mid Eighties, only Echo & The Bunnymen, The Cure, Siouxsie & The Banshees, The Smiths and The Cocteau Twins combined credibility and commercial appeal to anything like the same degree (U2 were only begrudgingly acknowledged by the music press). Even the Pet Shop Boys' microchip-off-the-old-block electro-pop wasn’t in the same league.

Eventually, they would see them all off. It was not deliberate; it was certainly nothing personal. New Order couldn't help themselves. They were just . . . better.

"Thieves Like Us", in spite of its stately 150-second intro, became a Top 20 hit in May, 1984. Dating back to the Arthur Baker sessions (who received a credit on the record as co-writer), and reputedly based around the hookline from Hot Chocolate‘s “Emma", it was a level above their previous efforts. All the usual elements were present and correct - Hook's bass, Gilbert's synth, that Morris pitter-patter, Sumner's lost-naif vocals - only the chemistry (as opposed to the chemicals) kicked in like never before. Majestic yet melancholic, with a melody that seemed to meander for ages, “Thieves Like Us" confirmed, if proof were needed, that New Order's examination of emotional decay and the destructive nature of love was every bit as profound and powerful as Joy Division's,

Less cryptic than Ian Curtis, though; more candid (more trite, say detractors of such disarming honesty), “It was quite a personal song," says Bernard Sumner of a lyric that includes the lines, "I’ve lived my life in the valleys/I've lived my life on the hills/I've lived my life on alcohol/I've lived my life on pills." He corrects the assumption that it is somehow upbeat. “It wasn’t optimistic at all,” he says of this deceptively pretty song “It was very pessimistic. It’s the sound of a person down on his knees, hoping and praying that things would get better. There's hope in it, but really it's . . . I don't really want to go any further into it; it's really quite personal. It’s a down song with a lot of hope in it."

Sumner, born in 1956 (the same year as Hook, a year before Morris, and five before Gilbert), grew up in Lower Broughton in Salford in a neighbourhood that was “completely decimated in the mid-Sixties" in a “Coronation Street terraced house" with a chemical factory at one end and 100 yards from the highly polluted River Irwell. Still just a boy, his entire neighbourhood was uprooted to a tower block over the river. Joy Division, for him, was “about the death of my community and my childhood. It was absolutely irretrievable."

This was undoubtedly the case for Ian Curtis, too, whose lyrics expressed the sense of dismay at the collapse of traditional family virtues and, later, the devastation of the North as a whole as it fell victim to late Seventies Thatcherite economic policy. On a more global level, apocalyptic dread informed his words, while a less specific existential despair couldn‘t help seeping into his troubled consciousness.

As for Sumner, he had in his background enough raw material for a dozen albums' worth of soul-searching lyrics. An only child and something of a dreamer. he lived with his grandparents and divorced mother until she re-married when he was 12. He used to hang out with a gang of evil local delinquents whose chosen form of evening entertainment was tormenting dogs, going on the rob, and breaking into people's cars. Bernard describes it as “a fairly difficult upbringing", his relationship with his mother - like that of many sons, to be fair - quite turbulent, although he insists that he “didn’t have bad parents or anything like that; they were good parents.

“But," he continues, filling in the gaps of this vivid portrait of his adolescence, “there was a lot of severe illness in my family which I won't go into in too much detail, some very severe illness which occurred round about the age of 16 and went on for quite a few years.

“Physical or mental? Physical. I had family members dying and . . . I don't want to go into it too much because it's too personal and too painful and I don't want people to feel sorry for me, but there was a lot of severe illness and death of family members.

“That," he concludes, “made me a bit black inside, because it was difficult to deal with. Basically. my family disintegrated through ill health. They're all dead now. It's quite a tragic story. What happened fucked me up really badly and that was the driving force in my life and my attitude."

The struggle to overcome misfortune and poverty, together with the sort of mundane or distressing problems that most of us have to face (his first marriage didn't last the Eighties) . . . none of these may be explicit in his lyrics for New Order. but they're all there, the events from his past, haunting those happy-sad words like so many spectres.

BY CONTRAST, THERE WAS “MY COCK'S AS BIG AS The M1". This was Sumner‘s original title for New Order's first single of 1985 (in the interim. there had been grisly Factory Benelux instrumental “Murder”, which was "thrown together one night in the studio" and contained a sample from the film, Caligula, which went “Crawl! Crawl! Crawl! I hate them!" and another from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey). it was promptly dropped (Bernard: “the B3293 is probably closer to the truth”) for the rather more poetic “The Perfect Kiss", a suitable title for such an awesome piece of Euro-romanticism.

Described by Stephen Morris as “a movie for the ears”, “The Perfect Kiss” was an orgasmotronic epic of quicksilver guitar and slivers of synth onto which were placed layer upon layer of keyboard-strings, complex bass and drum cross-rhythms and ricocheting, gizmo-triggered vocals.

Pure sonic architecture (and you should hear the 12-inch). The climax. a triumph of disco artifice, featured a Firepower pinball machine and a frog chorus - “flown in,” jokes Gillian Gilbert, “from the rain forests” - because the band couldn’t afford to pay Warner Brothers the phenomenal sum of money they were demanding for what they really wanted to close the show: Elmer J Fudd's “Th-th-th-that's all. folks!”

“The Perfect Kiss” was released simultaneously with New Order’s third album, Low-Life, one of the standout LPs of the year along with Propaganda's A Secret Wish, Scrlttl Politti's Cupid & Psyche, Prefab Sprout's Steve McQueen and Kate Bush's Hounds Of Love. “Elegia“ was a Philip Glass-inspired, atmospheric piece of modern classical music commissioned for an ID magazine film night. “Sunrise" was an intense rocker while the cinematic “Sooner Than You Think" was written by Sumner “in a pretty bloody unglamorous hotel in Ramsgate. like a boarding house" following a “pissed-up fight between some roadies . . , I wasn't a very happy chappy in those days."

That September, Factory - notorious for their ad hoc arrangements - reportedly drew up its first formal recording contracts, New Order's deal stipulating that the band only had to give six months' notice if they wished to leave the label. Two below-par singles followed in 1986: “State Of The Nation” and “Shell Shock", the letter written for John Hughes' Bratpack vehicle, Pretty In Pink. At the film's premiere in LA, remembers Morris, a gaggle of excited photographers and TV reporters mistook the road crew for New Order themselves, allowing the band to stroll in unrecognised amid a galaxy of stars.

Also in 1986. they performed alongside The Smiths, A Certain Ratio, The Fall and Echo & The Bunnymen at Manchester’s G-Mex for the Festival Of The 10th Summer (i.e. since punk) and appeared, again with The Smiths, at a benefit concert m Liverpool for the city’s councillors, then facing a legal dispute over rate-capping. Bernard, ill with flu, lost consciousness backstage in a chair, virtually sleep-walked onstage before the others by mistake and was assailed by flying beer cans from a crowd wrongly assuming he was a member of a much-loathed local act.

New Order’s fourth album, Brotherhood, came out in October, 1986. Admittedly a quiet time for

British rock, It was still unrivalled by anything that year bar The Smiths’ The Queen Is Dead. Recorded in Dublin, Liverpool and London, Sumner vaguely recalls “having a good time making it”.

Morris and Gilbert are noncommittal about the sessions. Hook is adamant: “It was like all the albums. We were so fucked off we couldn't wait to get home. I couldn't, anyway. But then, I fucking hate recording. I hate being in a studio. I hate it with a vengeance. It’s unbearable. Unfortunately, it’s essential for my job.”

Densely produced and overdubbed to the max, Brotherhood alternated between jangling guitars and juggernaut rhythms, punky thrashing and flawless electronics. “As It Is When It Was” was about as startling as hearing Kraftwerk strumming a folk song. "Bizarre Love Triangle”, the obvious single, was consummate synthpop with a killer chorus. The mighty "Angel Dust" concerned the fatal allure of narcotics.

“Rob, our manager, hated that," says Bernard. “It freaked him out. There’s another version of it called

‘Evil Dust'. 'Angel Dust' is 'angel dust' - a drug, like elephant tranquilliser; PCP I think It’s also

called. 'Evil dust’ is what they used to call cocaine.

"I don't want to get too specific about drugs because I don't want to start sounding like Shaun [Ryder, ex-Happy Mondays and Black Grape], and I don't want to be responsible for anyone getting into them, but yes, they can be a creative tool. ” Indeed, Sumner appeared on a BBC TV programme in 1996 discussing the creative potential of Prozac. “I’d never touch heroin, though. Not after seeing what it did to Martin [Hannett]. ”

There was a member of Happy Mondays (whose excellent second single, “Freaky Dancin'”, was produced by Sumner in 1986) present in the studio when New Order worked on five tracks - available to this day only on rare copies of the vinyl soundtrack - for a little-known US movie satire of televangelists called Salvation!, which starred Exene Cervenka of LA punk band, X, Cabaret

Voltaire and Arthur Baker also contributed music, but it

===========================

INSET:

BROTHERHOOD (1986)

Crystalline pop meets electroid rock. With its throbbing bass and sensuous pulse, “Paradise” was simply groovy. “All Day Long” tackled child abuse. “Every Little Counts” doffed its cap to Lou Reed’s “Walk On The Wild Side” while its lyric scaled new heights/plumbed new depths of

perversity (“Every second counts when I am with you/l think you are a pig, you should be in a zoo. ”)

Stephen Morris: “It was a bit higgledy-piggledy.”

Gillian Gilbert: “One side was acoustic, the other electronic. I don’t like the songs as much as our others. I don't like the sleeve. I don’t like the name."

Peter Hook: “There are some really good songs on it. Some of the best music is made when you're desperately unhappy or desperately fighting, isn’t it?”

Bernard Sumner: “It’s not as good as Low-Life. I remember going on holiday to Corfu, playing it on a

Walkman and thinking, 'Fucking hell, that’s shit.' What songs are on it? [Uncut reels off tracklisting].

Really? Well, fuck that, then. It sounds like a good album.”

===========================

Bernard still can’t quite believe some of those song titles. “‘Skullcrusher’! What a splendidly bad title that is! Fucking great. Maybe we should do it at one of our gigs. Trouble is, I can’t remember what it sounds like... I do remember Bez from the Mondays coming down to the studio. He was fast asleep on the couch behind me while I was singing the vocals, snoring his fucking head off. If you get the master tapes, I’m sure you’ll be able to hear him.”

Both Happy Mondays and New Order would be immediately receptive to the latest development in British music, which began when a group of south Londoners who spent the summer in Ibiza held reunion parties at the Project Club in Streatham and then relocated to Danny and Jenni Rampling’s celebrated Shoom nights: Acid House.

FIRST, NEW ORDER RELEASED the best double A-side of the Eighties. Side one: the unofficial national anthem of 1987, “True Faith" (with accompanying BRIT Award-winning video). Side two: the sublime electro murder ballad, “1963", with a gorgeous vocal from Sumner and a sick lyric about a jilted lover who shoots his girlfriend between the eyes - what the singer calls his “anti-sugar element". Factory also compiled Substance, a double CD featuring all of New Order’s singles and flipsides to date (sole omission: “Cries And Whispers”, from the “Everything's Gone Green" 12-inch). Substance is responsible for six million of New Order's 20 million total worldwide album sales to date. Not bad for an LP put together because Tony Wilson wanted to be able to play all of his favourite tracks by his favourite band in the car.

Then they went to Ibiza to see what all the fuss was about. On their return, they made Technique. regarded by many as their best album, one apparently imbued with the spirit of smiley culture, full of the joys of Ecstasy and nights spent clubbing and carousing.

Not so. Of the narcotic du jour, Stephen and Gillian say they “never touched the stuff", insisting that they stayed on the quiet part of the island. Peter Hook maintains that the band “hated each other in Ibiza", that they “went out separately", and that all they had to show for their interminable sojourn in the party capital of Europe were “12 drum tracks".

“Basically," he shakes his head, “we lost sight of each other. We stopped functioning as a group. It was really sad."

Bernard's view of their extended working holiday is only slightly more rosy, not least because he was there with new partner Sarah, very probably his muse for “True Faith" (opening line: “I feel so extraordinary‘) and “Touched By The Hand Of God".

“The DJs were fucking crap, because they kept switching records after 20 seconds. I preferred the more hardcore Acid House music they played at Spectrum and the warehouse parties in London. It was great staying up all night in the open air, but in the whole time we were there, all we recorded were the hi-hats for the album. And a guitar solo for ‘Guilty Partner’.

“We were about 15 miles from the centre. God, what a time that was. We used to drive over to San Antonio where all the English football fans were, get something to eat, then get shit-faced from that point onwards. We’d go to Amnesia 10km outside San Antonio and get really fucked-up there and stay until it closed at 6.30am, then we’d go back to San Antonio and go to a club called Manhattan which stayed open till 12.30pm. Then, stupidly, one of us would drive home about 25km.

“One night - no, morning; actually, it was probably the afternoon, to be honest - I was driving home and we got about half way and I saw this farmer ploughing his field, or doing something with a pitchfork, and I stopped the car, went over to him, gave him the car keys and told him to take us to another club. This poor farmer is standing there holding our car keys, staring at us sitting in the car. Steve [Morris] and Sarah said, ‘What the fuck are you doing?’ So Steve took the keys off the farmer, started the car, then crashed into a ditch."

New Order spent the remainder of their stay in Ibiza reluctantly entertaining gangs of marauding 18-30 types because their roadies fancied the women and wanted to impress them with their famous rock star employers.

“They were horrible," Bernard shudders. “They used to throw up all over the studio."

Notwithstanding the circumstances behind the recording, Technique, their first Number One LP, was unimpeachable. It had nothing to do, as many have claimed, with the plodding indie-dance of the “Madchester” scene. On Technique, the joins between rock and rhythm were airbrushed to the point of invisibility. It was superlative New Order.

To paraphrase a Melody Maker review, this was the state of the embers of the dying art of shimmering white funk.

Bernard Sumner had come into his own as a writer of been-through-the-mill, sensitive, adult confessional songwords. “I’ve seen what a man can do/l’ve seen all the hate of a woman, too, ” he sang on “Vanishing Point", while on “Dream Attack" the boy loner was finally ready to commit: “I can't be owned by no one/But I want to be with you. " As he asserts, “With Technique, the cycle from the total pessimism of Joy Division and the early New Order stuff to total optimism was complete. When I met Sarah, my whole life changed."

MIND YOU, THE TECHNIQUE TOUR ALMOST KILLED HIM. New Order had already circled the globe several times, including one memorable occasion in Bangkok where illegal drugs such as morphine were on sale in sweet shops.

Gillian Gilbert’s dyed red hair caused local pandemonium and the hotel porters carried sub-machine guns. Success, on whatever level or whatever form it took, just didn't faze them.

===========================

INSET:

A high point in a career full of peaks. Sheer automanik autobiography, this was Sumner’s Blood On The Tracks, at last. “Fine Time", complete with daft sheep bleats and a lyric addressed to a younger woman, saw an Aciiieeed-crazed Top Of The Pops performance almost as surreal as Kathyryn Bigelow’s heavy metal video parody for “Touched By The Hand Of God".

“Love Less” was aimed at an ex-lover who “won 't even talk to me" despite the singer having “spent a lifetime working on you. " “Round & Round" was sequenced in heaven and spiteful as hell (“If you mess with me, I’ll get rid of you"). “Run" got them sued by John Denver due to its apparent similarity to “Leaving On A Jet Plane”. The closing trio of “Mr Disco", “Vanishing Point" and “Dream Attack" threw down the gauntlet for electro-pop bands the world over. None of them dared to pick it up.

Bernard Sumner: “I wrote ‘Mr Disco' for the chicken-in-a-basket set. Sometimes I think it would be fun to write a load of crap. But that’s just my warped sense of humour. I like cheesy things and really bad jokes that aren't funny."

===========================

"I thought more about was my corn beef hash n the place was like than how successful we'd become," says Bernard.

The Monsters of Alternative Rock triple-header with PiL and The Sugarcubes was different, however: more dates, more extreme behaviour, just more.

"New Order," rock’s erstwhile hell-raiser told MTV reporters, “take more drugs than The Grateful Dead."

Peter Hook loved being on the road.

"It's a way of life," he told me. The others were less keen on being away from home for so long, staying in one strange city after another, surrounded by ghouls and groupies, dealers and hangers-on, quite apart from the inevitable pressures of performing and constantly having to re-programme their material every time a new piece of equipment arrived. Says Gillian. "We were sick of touring." In

her husband's opinion, rock groups should call it a day when they hit 30 (he was 32 in 1989).

After one exhausting night on the tiles in Chicago, Sumner - prone to nausea - was hospitalised.

“What happened was," he picks up the story, “I burned the lining off my stomach. See, I used to drink Pernod and orange juice. Now, at the start of the tour, I would have an inch of Pernod and five inches of orange juice. By the middle of the tour, it was one inch of orange juice and five inches of Pernod.

“So me and Sarah went out one night to this club in Chicago, and we were in this limo and we got to the club and I started coughing. I didn’t make it into the club; I just wanted to go back to the hotel - which isn't like me at all. I just started coughing and coughing and eventually I began to throw up at 3am and at four the next afternoon I was still being sick. I was just delirious - only this time I had not

had a drink. Maybe one drink.

“Anyway, we were due in Detroit the following evening and we were meant to have this big party with Kevin Saunderson and all those Detroit house guys, but I just couldn't get out of bed. I was sick for 12, 13 hours. That was the bad news. The good news was there was a hospital right across from the hotel; I could see it from my room. So all it meant doing was getting in a lift, going down, walking across the road, going in another lift and getting into the hospital bed. It was one of those Touched By The Hand Of God moments.

“It wasn’t just me, though. Hooky, Steve and Gillian used to drink a lot as well. But it was always me that ended up on the floor of the airport the next morning, throwing up.

“You know, I sometimes wonder if we hadn’t been so extreme, whether New Order would have disintegrated sooner."

===========================

INSET:

The difficult sixth album. You could almost smell the decay: the demise of Factory, the downfall of the Hacienda and the subsequent deterioration of the band’s relationships.

Still, for all that, some of New Order’s best music is here, spoiled only by Stephen Hague’s insufficiently hardcore production and the glutinous “soulful” warbling of the female backing singers. The first four tracks were singles: on “Regret”, Bernard yearns for normality; “World (The Price Of Love)” was curiously passionless commercial house; “Ruined In A Day” dealt in betrayal, although Sumner insists it wasn’t about current events; and “Spooky” was peerless techno-pop.

“Liar” was a poison dart aimed at a certain “King of Nothing", for which no prizes for guessing. “Everyone Everywhere” was magnificently moody. The too-glossy topcoat smothered the colossal sorrow of “Young Offender”. Near-instrumental “Avalanche” was Gillian’s own “Decades”.

Stephen Morris: “Strangely enough, I don’t mind it.”

Gillian Gilbert: “We listen to it a lot.”

Peter Hook: “We weren’t writing together. If we had, it might have turned out more like Technique."

Bernard Sumner.:“I was crawling up the walls in a room on my own, wondering why the others weren’t coming in.”

===========================

purveyors of digital existentialism did convene in 1990 to record a football song with England’s World Cup squad and comedian Keith Allen. Based on a rhythm track Morris and Gilbert had come up with while writing for TV series Making Out and credited to EnglandNeworder, “World In

Motion” became the group’s first Number One single that summer.

Over the next few years, the band undertook separate projects (Bernard; “I hate that word”), each one demonstrating, if nothing else, that New Order was in each member’s DNA. Electronic, Revenge and The Other Two all provided variations on a theme - electro-melancholia - with varying degrees of artistic and commercial success. Despite trying their damndest to express their differences, what heightened the poignancy of each venture were the essential similarities. When they decided to get

back together in 1993, it wasn’t easy. The cause of the friction was obvious: they were sick of the sight of each other, but they didn’t want to be apart.

Melodramatic as it sounded, Paul Morley’s assessment on neworderstory wasn’t far wrong: “They

seemed to love each other and hate each other.”

So they reunited for one more LP - Republic, their first for London Records - and it nearly split them up for good.

"Things started going pear-shaped with Factory," says master of understatement Stephen Morris.

Peter Hook is more specific. “The Hacienda was going downhill full tilt,” he says of an enterprise

allegedly costing each member of New Order £10,000 a month, “and Dry was as well. And we had a producer [Stephen Hague] for the first time [since Movement] which I actually agreed with because the four of us hated each other so much. He encouraged Bernard to write away from us, and that’s what it sounds like.

“Things reached a head all the time. It was all really, really difficult. The fact that you didn’t earn any money for a long, long time - until you were 32 or whatever - even though you’d been a successful group for 10 years, well, that’s something you wouldn’t put up with now. You’d just go fucking bonkers. But you didn't know anything about it then. So you’d say, ‘Rob, look, I can't pay the gas bill,’ and it would be like, ‘Oh, we’d better do another fucking tour, then.’ The only time we were

given something to do was when they’d run out of money. And you’d be like, ‘What? What? WHAT?’ It was like that for seven fucking years. We were so pissed off.

“I’m no businessman. I’ve got papers on my desk, but I’m naive when it comes to business matters. We all flirted with unsuccessful ventures. It was ego, mainly. My ego was really gratified by being part of the Hacienda. I used to lord it up. The bouncers would walk me through the door, all that crap. Free drinks all night. Brilliant. Absolutely wonderful. And then suddenly you wake up and it’s like, ‘Fucking hell, I lost how much?' I could have bought drinks for everybody in Manchester and still made a profit.

“It was heartwrenching. Heartbreaking. You had personal guarantees everywhere. The business side of it was dragging you down. Steve and Gillian in particular were almost destroyed by it. And they quit, leaving me, Bernard and Rob. But you just couldn’t crawl out of it. It was a shame. And it affected the music.”

Sumner corroborates Hook’s frank account of the Fall Of Factory and the breakdown of relations within the band. “We had tremendous business problems around the time of Republic. We were having weekly meetings with Rob and Tony Wilson; meanwhile, we’d be trying to write an album. And it was like, ‘If Factory goes down and the bankers pull out of the Hacienda, will you guarantee all the bank loans’ - which were hundreds of thousands of pounds - ‘with New Order’s assets?’

“Storm clouds were gathering on the horizon; everything seemed to be going wrong. The whole business side of the band was about to collapse, and really, we were making this album for nothing, because we were going to lose every penny.

“We’re probably very proud of the fact that we actually finished the LP, because we did talk at one point about going on strike, which is what we should have done. Factory didn’t just owe the banks loads of money, they owed us- and other bands - money. It was demoralising.

“On the other hand, we still liked Tony. It was a very confusing situation. Because it wasn’t like a normal business relationship where your boss fucks up and you say, ‘You twat, you fucking arsehole.’ I mean, I’m sure those words did pass our lips, but in our hearts we thought his intentions were good. It’s just that we felt the business side of things had been managed irresponsibly, whereas we had busted a gut delivering the goods - ie, enormous record sales.

"Suddenly, it seemed as though all those moments where I'd woken up on the floor of an airport being sick trying to catch an 8am flight had all been for nothing. I felt like a bomb was about to explode.

“There was a strange tension within the group. I was off working with Stephen Hague, or writing in a room on my own. I’d be crawling up the walls, thinking, ‘Why is no one coming in the room to see me?’ And the others thought I was being some kind of megalomaniac. I wanted them to come in and hang out with me. But they thought I didn’t want them in there.

“There had been too much getting out of it, too much talking behind people’s backs and not enough saying to people’s faces what you really thought and what the problems were that had created such a vile situation.

"It was a chain that had to be broken.”

AFTER THE RECRIMINATIONS, SUPPRESSED RAGE AND thwarted ambition - silence. New Order headlined 1993’s Reading Festival, after which performance they put down their instruments,