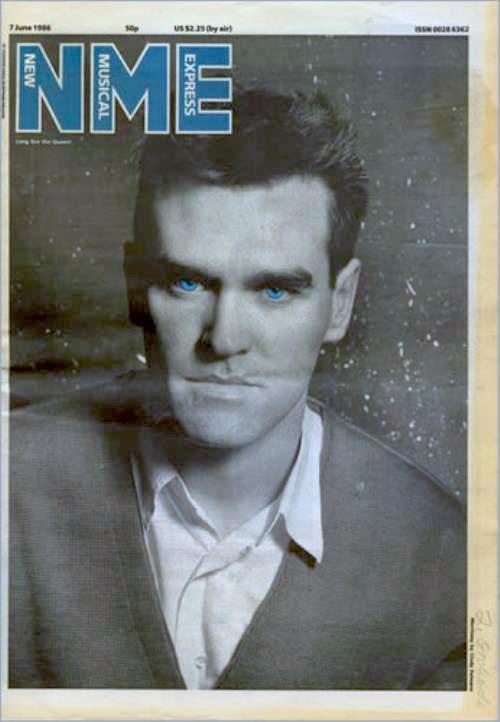

1986 06 07 The Smiths, NME

SOME MOTHERS DO 'AVE 'EM

A Gentleman At Leisure: the NME enters the Chelsea mews of one MORRISSEY, and what an accommodating fellow he is. How is life? One enquires, and receives in return impudence, tales of ordinary madness and insults to the Crown! And where pray, is that damn Smiths LP?

Interview: IAN PYE.

Photograph: LAWRENCE WATSON.

THE DOOR was ajar. Why not, I thought, and walked in. The flat appeared to be arranged on more than one floor and finding nobody on the first I climbed the stairs to the second.In the distance I could hear the maddeningly addictive chorus of a song that had recently become a personal favourite. "Some girls are bigger than others, some girls' mothers are bigger than other girls' mothers." The words, hypnotically, repeated over and over.

Making my way down a long corridor discreetly decorated with oatmeal-carpet and gilt framed oil paintings, I became aware of another noise, equally consistent, but cruder. The sound of rhythmic jumping perhaps.

It was obvious which room it was all coming from, but once at the threshold I hesitated . . .trying to weigh up the impact of such an intrusion. Really it was too late for second thoughts because by now I could see flailing shadows on the walls and the pounding seemed irresistible.

That reflection, caught in a huge, ornate mirror bordered either side by rich velvet curtains, was mesmeric. A mad whirl of florid material swishing out like a spinning umbrella. The figure turned dementedly on the spot and with each full revolution the toes of one foot hit the beat in time to the music.

Though the arms were both held high and arched, halfway between a ballerina and the highland fling one could clearly make out the flesh coloured wire of a hearing aid. I'd never seen Morrissey having such a wonderful time before. I'd never seen him grin like that.

I made one of those silly coughs you make to announce your presence . . .and your surprise.

"You're early!" he said, faintly put out. I calmed him with a flattering comment about his pearly white legs and as we both looked down remarked that he was wearing a tu-tu.

"Having some fun at last?" I ventured. Morrissey in "fun sensation" I thought to myself.

"If this ever gets out I'll kill you!" he snapped uncharacteristically. "Okay, okay," I replied, "as far as I'm concerned you wouldn't be caught embalmed in a tu-tu."

"That is neither here nor there," he assured me. "What matters . . . what matters is that I would never, ever, do anything as vulgar as having fun."

I decided to come back another time.

MORRISSEY'S ELEGANT retreat in one of Chelsea's most sought after lilac-scented squares is every bit the English gentleman's home. Admittedly the huge matt black ghetto blaster and the naked star-is-born lightbulbs round the bathroom mirror rupture the atmosphere somewhat, but the feel is decidedly classic. Sherlock Holmes might have taken up residence here, indulged himself with a little opium and a silk smoking jacket, solved a few cases.

"I could never really exist in any place unless it pleased me in every single aspect — which this almost practically does," he tells me while pouring tea into some fine china cups. "If I couldn't have really beautiful furniture I'd sleep in a shoe box" and, anticipating the response, adds "I was always like that really."

This rented mansion flat is his second home. He also owns a house in Manchester looked after for him by his mother, but his considerable book collection, spread either side of the marble fireplace, implies that at least half his soul has come down to London. I cannot find anything on these shelves that surprises me. Wilde, Dean, Beaton, Kael, Delaney... an unashamed shrine to his most revered icons.

Obsessed as he is by English culture, I ask him whether he's read any of the country's more contemporary writers. Ian McEwan, Graham Swift, Martin Amis even? He looks at me as if I'm clinically insane. "Not even on a wet day. One reads the name Leslie Thomas and thinks nobody with a name like that could possibly write an interesting book."

When I point out that he's been responsible for popularising a group with the blandest name in the history of pop, he says, feigning weariness, "Yes I know . . . it's been a great strain. You see before you a mere cast of a man," and bursts out laughing.

On the contrary he looks the picture of health compared to the days when only his quif seemed well-fed, so perhaps there's something to be said for clinging to one's familiar obsessions. It seems extraordinary that he's still reading the latest books on the Moors Murderers and James Dean. It's all meticulously deliberate. "I'm restrictive," he notes with the hint of a smirk. "I can lapse into Jane Austen, never quite Dickens, but nothing outrageously modern really."

A request to peruse the record collection is declined. "I keep mine in Manchester. That's the sort of thing I do in private. They're little bathroom activities playing records. I mean I could despise a person if I came across a particular record in their possession however kind that person had been to me in the past. One rancid LP and I'd be lashing out at their shins!" I make a mental note to bury that first Madonna LP should he ever return the visit.

Further conversation only confirms that Morrissey is diligently chiselling away at the same granite image that was first unveiled when The Smiths released their debut single 'Hand In Glove' in May of 1983. Except the statue's almost finished now. It's more a question of polishing, of honing a creation that's almost Luddite in its refusal to accept the present let alone the future.

With his gods in a glass case, the litany also embraces George Formby, British films of the '60's especially A Taste Of Honey, stock tragedies like Monroe, a mind virtually closed to most contemporary music... "not another hip hop record or whatever they're called"... artwork for the new Smiths LP 'The Queen Is Dead' that borders on parody, and an archetypal film still of a serene Alain Delon, it's easy to wonder how The Smiths could ever do anything fresh.

The singles have kept coming though and, with the possible exception of 'Shakespeare's Sister,' all have been worth treasuring. But close observers have seen the stumbles. A long and acrimonious kitchen sink to court room row with their label Rough Trade (once an alliance between indie and great white hope that was depicted as some kind of political statement) delaying the release of the new LP by eight months - very rock biz, that - whingeing in the camp about low chart placings and, worse still, the debilitating curse of pop groups throughout the known universe that is euphemistically known as "personal problems".

That said, for their supremely dedicated followers The Smiths remain the only group worth bothering with, and for once these fans aren't far wrong. On first hearing, 'The Queen Is Dead' might be assumed another exercise in consummate Smithdom. After all, nothing much has changed on the surface. The same line-up, guitars and drums, no horns or keyboards, no fanciful departures. Yet further listening reveals a record touched by a musical and lyrical vision that dwarves most around them.

Its pleasures are all the more heightened for their rarity. The Smiths' breakthrough in '83 was sudden and exhilarating. Three LPs and countless singles later and nobody's followed them. The indie scene isn't so much a ghetto anymore, it's a shantytown from which there's no escape. And the majors preserve their tidy and mostly vacuous domain with a fervent sense of what is right and wrong for mass consumption.

While championing Easterhouse and at one stage The Woodentops (who he now insists on calling The Sudden Flops, a comment that reflects not just the dashed expectations but their campaign against him which culminated with a bomb 'threat' - such serious young boys!) Morrissey has now adopted a posture of extreme pessimism, placing his group as the full stop at the end of Rock Babylon.

"But what else can happen," he says matter of factly. "Is there anything else to happen? No there isn't, because the industry is dying, and the music is dying. It's like if you look at the film industry, there's really nothing else that can happen. All the stories of human life have been told.

"I felt there was one last vein untapped and we tapped it. Now that source has been used there's really only cultural desert in front of us, nothing but cultural desert.

"Even if you detest The Smiths you have to admit they have their own corner, but it's not really possible to build one's own corner anymore. That The Smiths have their own corner is in itself quite remarkable.

"I mean I was ill and I said I was ill. Nobody had ever said that they were ill before. Within this beautiful sexy syndrome I popularised NHS spectacles! I didn't popularise the hearing aid, thank God that didn't catch on, but that again was one of my statements. Not a prop because that sounds like marshmallow shoes or a polka dot suit. I mean I really maintain to this day that even the whole flowers element was remarkably creative, never whacky or stupid.

"We can say yes Morrissey that silly old eccentric, but I think it's nice if somebody who is eccentric can break through. Everybody follows the same rules and does exactly what they're told. All modern groups state the expected - fluently, but who cares?"

Let's talk about the new LP.

"Why, for heaven's sake?"

The Smiths new LP begins with the title track and a few verses of Cicely Courtneidge's shambling but defiant version of 'Take Me Back To Dear Old Blighty' from The L Shaped Room. The song, as it did in the film, speaks for a certain Englishness, indeed for Morrissey a priceless Englishness that has vanished forever.

In the original scene, Courtneidge plays a forgotten war time performer living out her last days in a shabby flat in Fulham. She revives the half-remembered singalong one Christmas surrounded by the new cosmopolitan Londoners. It's a scene heavy with pathos and one that conjures up an England perhaps more gentle and certainly more simple in its charms. A place which eulogised witty conversation, well turned letters, corner shops and theatrical hams.

'The Queen Is Dead' isn't just a straight lament however. It uses the Queen as a double edged metaphor for a world we have lost and the meaningless heritage of the monarchy in 1986. It's also one of the most exciting rock songs The Smiths have ever made, Johnny Marr's music pulling the listener into a giddying black farce.

"I didn't want to attack the monarchy in a sort of beer monster way," he explains in that ever more seductive Manchester brogue. "But I find as time goes by this happiness we had slowly slips away and is replaced by something that is wholly grey and wholly saddening. The very idea of the monarchy and the Queen of England is being reinforced and made to seem more useful than it really is."

I suggest that the hardest thing to stomach about the monarchy these days is the way they're increasingly used as political camouflage. Five million unemployed? Have another Royal Wedding, chaps.

"Oh yes it's disgusting. When you consider what minimal contribution they make in helping people. They never under any circumstances make a useful statement about the world or people's lives. The whole thing seems like a joke, a hideous joke. We don't believe in leprachauns so why should we believe in the Queen?

"And when one looks at all the individuals within the Royal Family they're so magnificently, unaccountably and unpardonably boring! I mean Diana herself has never in her lifetime uttered one statement that has been of any use to any member of the human race. If we have to put up with these ugly individuals why can't they at least do something off the mark!"

But if the Royal Family do achieve something it's to bring American tourists to this country which as you might expect is hardly a source of joy for dear Morrissey. It goes deeper than that though. His disgust for our new England is fuelled by its steady Americanisation. The missiles, the burger bars, the one-dimensional me generation lust for gold-plated, designer-stamped success.

Unwillingly dragged screaming into the 20th century Morrissey seems in so many ways closer to his previous generation than his successors. In fact, he doesn't mind saying so. For him the future is an encroaching nightmare.

"These people may have no sense of the social," he says of the '80s survivalists, "but more importantly they also have no sense of taste. They have such bad taste in every area and that's the main thing that worries me."

Which all begins to make Morrissey sound like a sentimental old nostalgic. This he would deny to the death and while it's easy to sympathise with his loathing for Yuppie culture and the loss of English gentility he does spend an enormous amount of time looking over his shoulder.

I always thought he was a bit long in the tooth to be singing about school days on 'The Headmaster Ritual,' and the song 'Meat Is Murder' has a worryingly sixth form quality to it as well. Now, on 'The Queen Is Dead,' and having just turned 27, he presents us with songs about leaving home!

"Yes, yes, but..." he says in his most engaging purr, which roughly translated means have an opinion but for Oscar's sake pull yourself together and see some sense. "Don't you find that even now certain memories of school still cling and then suddenly you remember the day in 1963 when somebody did something wholly insignificant to you?"

To be honest, I don't, there's always more recent memories ready to haunt you.

Didn't he realise that most people of his age had been through their lads-smoking-behind-the-bike-shed stage, the romance and marriage stage, and were now on to the divorce and mark-two lover stage?

"And I'm still waiting to be chosen for the swimming team!"

"But I do feel in an absolute way that I've been sleepwalking for 26 years. On the bleak moments when I came to consciousness I was reading the New Statesman. You see I never did all those trivial pursuits. I did read all those music magazines. I mean, I can remember when NME was 12 pence! I can remember when Disc was six pence. I can remember when you could buy all four weekly magazines for under 50 pence!"

One thing Morrissey has learnt to do is to feel burdened by the pressures of success. The vehicle for his complaint is 'Frankly Mr Shankly,' a brilliant piece of modern music hall that carefully offsets the poverty of the privileged with an ironical jauntiness. It's one of the LP's landmarks and defines new ground for The Smiths, but those lyrics? It forces the question aren't you just moaning about fame like they always do?

"Yes! Like they always do!" he replies with an extravagant sweep of his arm. "Yes I'm moaning about fame," he repeats caressing his brow with the most melodramatic hands in the history of the stage. "I was reaching for the rubber but I thought, well no, I do want to complain, I do want to moan. Complaining is so unmanly, which is why I do it so well!"

As the laughter trails away, he continues. "Yes... fame, fame, fatal fame can play hideous tricks on the brain. It really is so odd, and I think I've said this before - God I suddenly sounded like Roy Hattersly - when one reaches so painfully for something and suddenly it's flooding over one's body, there is pain in the pleasure. Don't get me wrong, I still want it, and I still need it but...

"Even though you can receive 500 letters from people who will say that the record made me feel completely alive - suddenly doing something remarkably simple like making a candle can seem more intriguing in a perverted sense than writing another song. But what is anything without pain?"

In the past much has been made of Morrissey's stock heroes, the spectres of Wilde and Dean not just hovering in the background but actually there, embodied in his flamboyant and frequently self-deprecating humour and the exquisitely tousled quiff set off against the eternal faded blue jeans. His absorption of those characters has played tricks with both time and image, yet much of it, particularly the rugged Dean connotations, is a smokescreen.

The lyrics of the new LP, littered as they are with notions of home and leaving home, put you in no doubt as to who Morrissey's real hero, or heroine is... his mother. But this isn't easy to talk about. Not that he doesn't agree with my suggestion - it's just that for once this is one subject he would prefer to avoid in print.

"Mentally I don't believe I've ever left home," he concedes. "You always think that as life progresses you're going to open different doors. But the shock to me is that you actually don't... But who will accept describing one's life as a really bad dream, Ian? Millions of people will just because it's never stated, it's not implausible and it's not dramatic."

For every song exploring the special pain of loneliness on "The Queen Is Dead" - "if you're so clever why are you on your own tonight?" he croons magnificently on the chilling "I Know It's Over" - there's a comic equivalent to balance things out. It's refreshing to know that even the prince of misery likes to have a good laugh now and again.

Quite purposefully a record of extremes, it jumps with wild abandon from the tragic to the humorous. The title song manages to combine both at the same time. Having invaded The Palace he confronts The Queen with a rhyme more outrageous than the original crime - "And so, I broke into the Palace with a sponge and rusty spanner, she said: Eh, I know you and you cannot sing, I said: That's nothing - you should hear me play pianer".

He also dares to suggest that Charles might brighten all our lives with a dash of transvestism and that the clergy have been doing it for years anyway which proves that cheek isn't just the province of journalists and market traders.

Taking on the guise of the agony aunt - he worships every dribble from the lips of Claire Rayner and wilts with envy every time she reveals another chintzy outfit - he says "Sometimes I think, well Morrissey, you've got them sitting by the bed with their pills you'd better do something quick!"

Those who like to picture him as the last of the great bedroom angst merchants might be enlightened to discover that the apogee of English nudge 'n' wink humour, the Carry On saga, gets his selective approval.

"There were 27 films made in all," he notes authoritatively, "and at least six of them are high art. They finished artistically in '68 but it went on, I think, to '76 or '78. When you think of Charles Hawtrey, Kenneth Williams, Hattie Jacques, Barbara Windsor, Joan Sims, Sid James... the wealth of talent!

"They've tried to recreate those things again in The Comic Strip or whatever and those awful, offensive Nine O'Clock News things. They tried to recreate that clannishness of comedians and it doesn't work. It's not just a matter of talent, or getting people together. It's something else."

And if you're still in doubt over Morrissey's comic sensibility let me just tell you that currently his favourite TV show is Cagney And Lacey.

"You don't watch it? My, you're crumbling before me!"

He's always complained that people have failed to notice the humour so perhaps that explains the generous helping. Much of it may be disturbingly black, the gallows jests of a condemned man, but most importantly it works. 'Cemetry Gates' delves into more mirth and morbidity.

"It's like famous last words. So many people's last words were so riotously memorable. Howard Devoto was telling me about - we were in a cemetery because we've decided to do a tour of London cemeteries, cheerful little buggers that we are, you know get the Guinness and cheese butties out and head down to Brompton Cemetery - some old corporal dying, smothered in blood, having a very artistic coronary arrest and his right-hand man was saying 'Don't be silly Charles, cheer up, cheer up, we're going to Bognor this weekend'. And he turned round to his friend and said 'Bugger Bognor!' and 'Bugger Bognor!' actually appeared on his tombstone as his famous last words. I think that should be an LP title... 'Bugger Bognor!'."

'Cemetery Gates' doesn't just make jokes about grave humour though. It's concerned with the prickly matter of plagiarisation. He says he's always been happy to admit he's borrowed a few lines or two, most of them from movies. A Taste Of Honey, Rebel Without A Cause, and Sleuth have all aided the Morrissey muse.

What he objects to are those smug anal retentives who think they've found you out and denounce your entire canon of work as tainted by theft. "Obviously most people who write do borrow from other sources," he contends. "They steal from other's clothes lines. I mentioned the line 'I dreamt about you last night and I fell out of bed twice' in 'Reel Around The Fountain,' which comes directly from A Taste Of Honey, and to this day I'm whipped persistently for the use of that line.

"I've never made any secret of the fact that at least 50 percent of my reason for writing can be blamed on Shelagh Delaney who wrote A Taste Of Honey. And 'This Night Has Opened My Eyes' is a Taste Of Honey song - putting the entire play to words. But I have never in my life made any secrets of my reference points.

"Just because there's one line that's a direct lift people will now say to me that 'Reel Around The Fountain' is worthless, ignoringthe rest of it which almost certainly comes from my brain. Oscar Wilde... I've found so many instances where he has directly lifted from others. To me that's fine. But because I'm so serious about writing, people are so serious about tripping me up."

I'm sure that many will find the undercurrent of death and depression on 'The Queen Is Dead' difficult to cope with. This time round Morrissey's special brand of terminal humour may lighten the load but much of the material is gloriously doomy. What's more, it seems hard to square with the relatively cheerful young man I see before me.

And when I tell him that he certainly looks better and laughs more than he used to, he shakes his head as if I was trying to attack the whole foundations of his career. I need glasses, he splutters, I need to look again.

"I'm not happy, I'm not," he cries. "I know a lot of people at this stage will throw down the magazine and say, well Morrissey, this is your platform, this is our proud badge that you wear, that you gladly cycle on the edge of a cliff and you're ready to throw your handlebars to the wind.

"But almost every aspect of human life really quite seriously depresses me... I do feel that all those tags, the depressive, the monotony, all tags I've dodged or denied are probably absolutely accurate. When you put me next to Five Star and judge the whole thing against the bouncingly moronic attitude that is so useful if one wants a job in the music industry, then yes I am a depressive. If I wasn't doing this I don't honestly believe that I would want to live. And one hesitates about making such statements because however one makes them it never seems useful."

That somebody of his nature exists within the British pop industry at all is intriguing to say the least but methinks he does exaggerate the case. The Smiths sheer output for a start, they can release singles with a rapidity that seems to spray the charts like a machine gun compared to their weary rivals; and their music, only a handful can make pop as beautiful as theirs; all argue against the leaden weight of a true depressive.

What Morrissey does appear to suffer from is a state of permanent adolescence. Just as he refuses to leave the 19th Century he refuses to leave home. "I know," he remarks with a kind of blissful resignation. "It's a national disgrace! We know there's a shame attached to it. If you're still living with your parents at 19 you're considered some club-footed bespectacled monster of repressed sexuality - which is in every case absolutely true!"

The hysterical fit of giggling that follows is a sight for sore eyes.

He's not been slow before to criticise Joy Division for their supposed suicide chic and who would deny that group gained another vital dimension in the aftermath of Ian Curtis's death. Any image has its price and The Smiths excuse theirs through artistic integrity. But the fact remains that some of these songs aren't far short of aesthetic Exit manuals.

Discovering that six people "who were alarmingly dedicated to The Smiths" have taken their lives over the last two years suggests that this isn't simply melodrama. "Their friends and parents wrote to me after they'd died," he explains. "It's something that shouldn't really be as hard to speak about as it is because if people are basically unhappy and people basically want to die then they will.

"Although it's very hard for many people to accept, I do actually respect suicide because it is having control over one's life. It's the strongest statement anyone can make and people aren't really strong. You could say it was negative leaving the world but if people's lives are so enriched in the first place then ideas of suicide would never occur. Most people as we know lead desperate and hollow lives.

"I can't feel responsible... totally. I know that in most instances that for the last sad period of these people's lives at least having The Smiths was useful to them."

Had he ever considered suicide himself?

"About 183 times, yes. I think you reach the point where you can no longer think of your parents and the people you'll leave behind. You go beyond that stage and you can only think of yourself.

"It's a situation people can so easily toy with and find very romantic. All the great pop stars which nobody ever cared about when they existed - their deaths throw a magnificently alluring colouration on to their total existence as human beings. Whereas if most of these people had lived, nobody would have cared a lot.

"I think suicide intrigues everybody. And yet it's one of those things that nobody can ever really talk about in an interesting way. You always have the usual, Oh it's so negative, it's so wrong attitude."

Isn't your fascination with death, I argue, a convenient way of giving your life meaning when you should be looking elsewhere?

"No, I don't think so. So many of the people that I admire took their lives... Stevie Smith, Sylvia Plath, James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Rachael Roberts... there are many..."

One new song, the delicious 'Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others,' must be the most evocative verse about nothing ever written. For some reason all kinds of permutations go through your mind when it's playing, a hilarious send up of Page Three amongst others, and one can't help be reminded that Morrissey doesn't write songs about women - unless they happen to be his mother.

"Well there are songs about women," he claims before collapsing into laughter again. "You just have to dig for them. You have to dig very deep for them. I do want to write about women. The whole idea of womanhood is something that to me is largely unexplored. I'm realising things about women that I never realised before and 'Some Girls' is just taking it down to the basic absurdity of recognizing the contours to one's body. The fact that I've scuttled through 26 years of life without ever noticing that the contours of the body are different is an outrageous farce!"

Yet there are signs that he may one day grow up, though I'm certainly not implying that this is something to be encouraged. The longest period of celibacy outside of a Buddhist monastery has been broken. "I lapsed slightly," he admits. "I was caught off guard as it were. But I return of course as triumphant as ever to the most implausible, unbelievable, necessary absurd situation that could befall any intelligent person."

Ever fallen in love.

"Yes, no, yes, no, yes, no... and that's about as clear as I can be!"

In an arena inhabited by the most ridiculous macho monsters, The Smiths present an image that is absolutely non-phallic. What sexuality the group do possess is of a far more natural kind than that presented by the crotch fixated bimbos of MTV world. Not everybody can accept this. When Smash Hits set Morrissey up with friend Peter Burns for a predictable queen bitch stand off they apparently wrote what they wanted.

"It was a completely civil and honest interview with Pete and I," he recalls, "and they turned us into Hinge And Bracket. I was supposed to have called him Joan Collins and... it was completely laced with camp symbolism - which never occurred. I was really upset... they made us look like a couple of dippy queens."

I wonder what he thought of the sexual models on offer at the moment. Madonna, Prince, Boy George?

"Obviously Madonna reinforces everything absurd and offensive. Desperate womanhood. Madonna is closer to organised prostitution than anything else. I mean the music industry is obviously prostitution anyway but there are degrees.

"For me Prince conveys nothing. The fact that he's successful in America is interesting simply because he's mildly fey and that hasn't happened before there. Boy George, again I think he really doesn't say anything either."

In their unique position as successful outsiders The Smiths have escaped the kind of coverage most pop stars have to enjoy or endure in the national press. There have been other attempts to dig the dirt. The latest is a book by Mick Middles which mixes anecdote with the kind of trainspotter mentality only the most fervent fan could lap up. For Morrissey it proved a fascinating read.

"I don't really expect his book to be found anywhere other than the fiction section! It was so riddled with inaccuracies that to me it was a thrilling commodity. I learnt so much. If I have any doubt about the future I need only glance at this book to know what to do, so in that sense Mick Muddled has been of religious assistance in more ways than one. I had no idea for instance that at one point I was going to manage Theatre Of Hate. I don't even know who Theatre Of Hate are. So to me it was an illuminating collection of gossip."

That the Smiths wish to do more than serenade the world in its twilight hours is born out by a constant theme that might be summed up as a plea for care and compassion. With this in mind and allowing for the fact that they embody the sensibilities of a vast section of young people across the world it seems amazing they weren't asked to take part in Band Aid. Or does it?

According to Morrissey, "nobody younger than Bob Geldof was allowed near that stage because otherwise The Boomtown Rats would have seemed like a collection of Brontasaurasi. And nobody who had not sold a million was allowed near the stage. Have the Boomtown Rats sold a million? Remarkable group if they have!"

Not even the broadening out of the appeal to include the likes of Fashion Aid and Sports Aid has done anything to change his original attitude of scorn. We've been blinded by the money raised, he argues, fooled by a show biz sham.

"If it had dealt with a domestic issue I don't believe it would have received any attention whatsoever. I'm sure the organisers would have been kicked to death. If we talk about unemployment in England we're slapped across the face. I think there was something almost glamorous about the whole Ethiopian epic. In the first instance it was far away, overseas. Pop stars, film stars, it was and still is escapism.

"The glamour veils a more serious question, knowing the world is controlled why are such things allowed to happen. But I'm also appalled that the guilt of such an occurrence should be placed upon the shoulders of the British public. It's absurd. How many people in England live below the poverty line?

"I got a foul scent when it first occurred and I still get the same smell. It's an inch away from Hollywood. When will the film appear, the solo LP is on the horizon, the book is here. It's bully tactics and dining out with royalty. It's not shaking Margaret Thatcher by the lapels when he had the chance. No... and hearing Bob talk so lovingly about Prince Charles! To me it's so unreal. I never mentioned the word greed!"

The Smiths did, however, play the last date of the Red Wedge tour, but not without reservations.

"Without wishing to sound pugnaciously ponsified I wasn't terribly impassioned by the gesture," he says with a smile. "I thought the overall presentaion was pretty middle-aged. And I can't really see anything especially useful in Neil Kinnock. I don't feel any alliance with him but if one must vote this is where I feel the black X should go. So that was why we made a very brief, but stormy appearance.

"When we took to the stage the audience reeled back in horror. They took their walkmans off and threw down their cardigans. Suddenly the place was alight, aflame with passion!"

Together we talk about the future, the dreaded beast of Morrissey's worst dreams. We both agree Margaret Thatcher will probably kill us all. Rough Trade won't be insisiting on any more videos and The Smiths won't be making them. Andy Rourke has rejoined the group. Craig Gannon is the new fifth member but they aren't turning into The Rolling Stones, just playing with them; Johnny Marr is working on two off-shoot projects, one with Keith Richards and the other with Bryan Ferry. There's a British and American tour to come and a new single, 'Panic'.

You could almost say everything looks rosy. His head tilted to one side, enjoying the comfort of a favourite armchair, Morrissey is relaxed. The world's favourite misery goat seems radiant for a man in torment. He's left school, left home (almost), what next... a relationship, I suggest as a parting thought.

"I wanted to say this to you," he says slowly in a tone of confidentiality. "I always thought my genitals were the result of some crude practical joke. I remember an NME interview in the very early 1970s - it was Gary Glitter. It concluded with the remark 'the constant reminder that there's something between his legs'. And I thought it might be quite fitting to end this with... the constant reminder that there's absolutely nothing between his legs!"

"I'm sure you're disappointing millions!"

"Ian... I doubt it... which is very disappointing to me."

Comments

Post a Comment