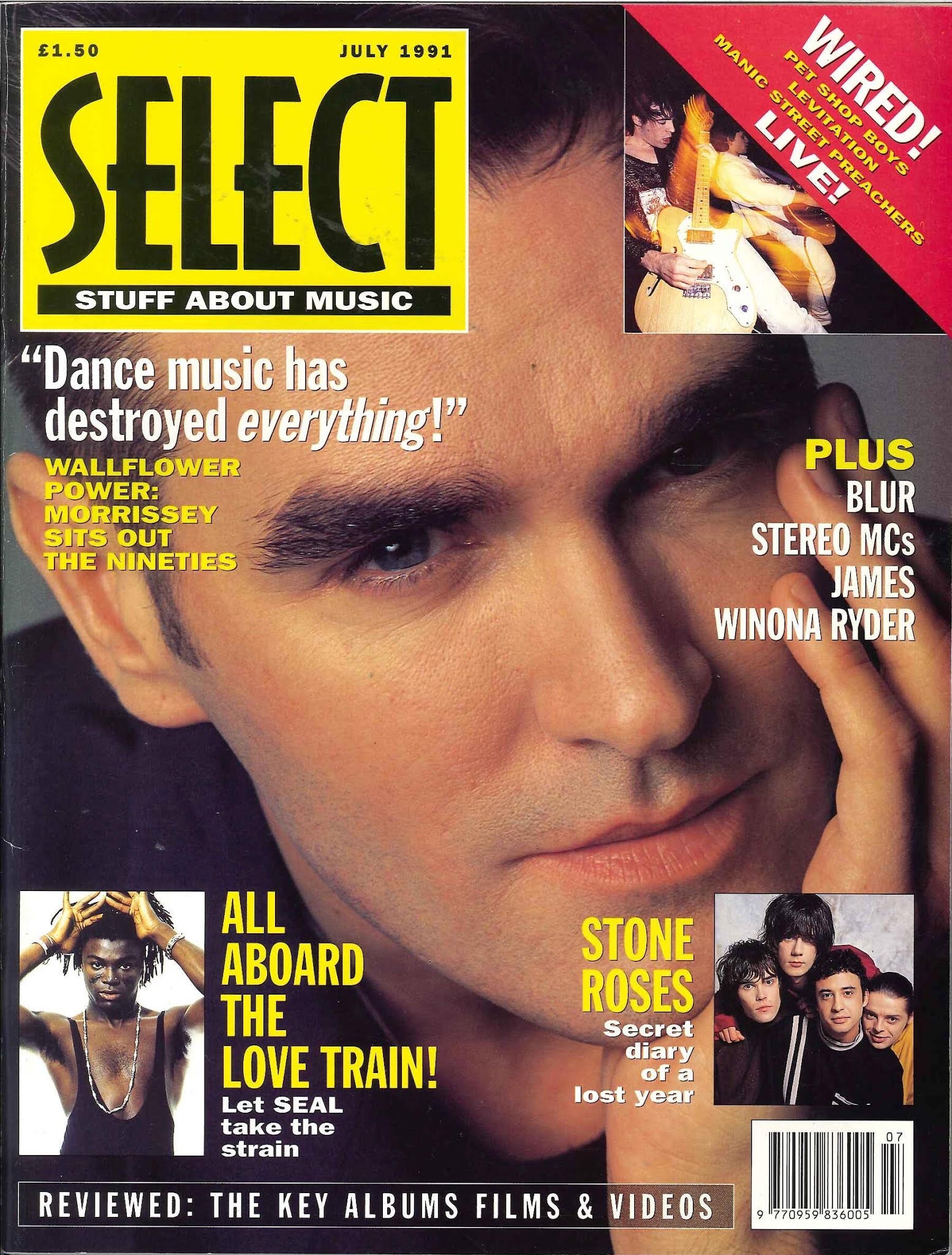

1991 07 Morrissey, Select

The Manchester scene is press-created, shallow, turgid, "a shuddering disappointment". Dance music has destroyed everything, it's "totally shocking and revolting". You are Morrissey and 1991 is becoming a nightmare...

Sitting at a table in the lobby of Manchester's famed Midland Hotel, a stately red-brick building on Mosley Street where C S Rolls and Henry Royce first met in 1904 to talk luxury automobiles, Morrissey is sipping herbal tea and feeling just miserable.

That's nothing new, of course, except that today he has a physical, tangible reason for it.

"Today?" he asks, raising his prominent eyebrows, dubious of the initial line of questioning. "Well, let's see. Today I've been suffering slightly because I've had a terrible bout of flu, which can't be of any interest to anyone at all."

He puckers his lips to one side, forming an understated - and presumably unintended - Billy Idol like snarl.

"I spent the entire morning covered from head to foot in phlegm," he goes on. "Which is not terribly romantic."

Morrissey's hibernation, however, seems to be over. He's out playing gigs again to a rabidly enthusiastic flock - the first gig of his tour, at Dublin's Stadium, sold out in three quarters of an hour - and talks of happiness, peace and friendship in a way that would have seemed ludicrous in 1986.

It took him long enough. A disastrous 1990 saw his projected second album collapse in doubt and mediocrity, his chart profile slump to its lowest ever and - that most cruelly symbolic of gestures - a stop-gap cheapo compilation album released to give its maker time to think.

'Bona Drag', the album in question, got a bemused thumbs up from the critics, but where, everyone asked, was the follow-up to 'Viva Hate'? Could Morrissey deliver another album? Had he run out of things to say?

'Kill Uncle' divided the critics in halcyon Morrissey fashion. Select gave it four out of five, declaring it "a success, dammit, a success"; one of the weeklies ended their review with the prosaic rationale "Morrissey doesn't matter".

The man in question seems, in classic Mozz fashion, ever so slightly above these controversies. He awaits interrogation with amused, saintly patience...

Are you any happier these days, Morrissey?

The older I get - and I'm now stumbling towards my 32nd year - I do feel happier. There's something about life that's slightly easier. There are fewer expectations to be entirely and insufferably hip.

There's a song on 'Kill Uncle' called 'Found Found Found' which goes, "Found, found, found/Someone who's worth it in this murkiness/Someone who's never seeming scheming". It suggest you may finally have found someone to have a sexual relationship with.

It's not necessarily sexual. I don't think I mention sexuality in the song at all. But even in the limited capacity of finding a real friend and realising that it actually does take a lifetime to find one, I'm always slightly exalted by coming across someone with whom one has an instant rapport, an instant harmony...

You've become a friend of Michael Stipe, haven't you?

Michael has written to me for a while and I was not quite sure what to think of his letters. Then we met several times in London and went on these extensive walks in which we would just keep walking in huge circles around London and through Hyde Park. We just walked and talked and... that's always been very difficult for me. Michael is a very generous, very kind person.

Do you think you'll work together?

It isn't decided yet what we'll do, but it would be nice to do something unusual. Some Righteous Brothers type thing. I'd like to lead the way, actually. I think it could be one of those funny historic bits of pop television that's so rare these days, especially in England.

What was the first record you ever bought?

'Come And Stay With Me,' by Marianne Faithfull. When I was six.

I lost myself to music at a very early age, and I remained there.

It's so easy to throw that old word 'obsession' around. We often hear about, Oh, I'm obsessed with that, I'm obsessed with music, I'm obsessed with theorising about music. All of us secretly think we're musicologists and that only we know what's good and what's bad. But the word 'obsession' - which is frequently applied to me - is a pretty dangerous one, really.

I did fall in love with the voices I heard, whether they were male or female. I loved those people. I really, really did love those people. For what it was worth, I gave them my life... my youth. Beyond the perimeter of pop music there was a drop at the edge of the world.

You wrote a book about the New York Dolls...

The New York Dolls were my private 'Heartbreak Hotel,' in the sense that they were as important to me as Elvis Presley was important to the entire language of rock 'n' roll. They were my only friends. I firmly believed that. I knew those people intimately. I knew everything about their lives. Of course, I really didn't, but in my own sheltered way I certainly thought I did.

To me, the New York Dolls were the best group ever to come out of America, and they were loathed by America at that time. Sadly, they were reasonably appreciated only after it was too late. The New York Dolls were an early version of the Sex Pistols, and if Americans and the American music industry had only been alert enough in 1972 and 1973, the New York Dolls could have changed so much. But, not to be.

What was it like being in Manchester during punk?

It was a terribly exciting time. I was at all the right places at all the right times, and I saw all the right groups at all the right times. The Sex Pistols played their first show just three yards away from where we're sitting right now, at the Free Trade Hall. It was a fantastic night. Nobody moved. People sat in awe.

It was a very historic night, although I know it's quite standard to look back upon rock history and say, Oh, yes, that was historic, it was moving, it was such a great night. And now that I think about it, it actually wasn't. It was a dank night that only history has given a bit of color to.

But those early appearances in Manchester by the Sex Pistols and the Buzzcocks, were truly... er, I hate the word 'magical', but I have to use it, I suppose.

So your life up until then hadn't been that magical?

I'm hard pressed to think of any pleasantries at all.

But it obviously had a huge influence on the way that you write?

I think that our lives are so indelibly, irreversibly shaped at a young age that there is very little we can do - although we always want to think that change is possible and that perhaps we'll go through some magical transformation, especially with the arrival of 30 and then 40. But it doesn't happen.

How does it feel to be playing to people half your age?

It's so abstract to me when I get letters from people who buy my records who weren't even alive when I was watching David Bowie onstage. It's that peculiar march of time.

There's a famous quote which goes something like, 'You are what you are, having secretly become what you wanted to be'. Maybe there's some truth to that. We like to think that society shapes us, but I don't think that that's the way it happens.

Do you insist on your fans being as obsessive about you as you were about your heroes?

When I was young, I instantly excluded the human race in favour of pop music, and you can't live a fulfilled existence like that. People are invariably there. You have to go to school; you have to try to communicate with those around you.

But when you've sealed up your bedroom doors and you've blackened your windows, and all you want in the world are those tiny crackles that are about to introduce that record - and you love the crackles that you hear from the needle on the vinyl as much as you love what will follow - then I don't think you will turn out to be a very level-headed human being. Music is like a drug, but there are no rehabiliation centres.

Are you still an addict?

Tonight, on this very day that you and I are speaking, I will go home and I will play music very, very, very loudly, and I will be absolutely transported to a delightful new planet. I will listen to a record which I can't stop playing at the moment, a single called 'Good Timin'' by Jimmy Jones - an old American MGM yellow label record.

It's just simple, straight, boring, dull, floppy old pop music, but to me it's... (he lowers his voice to a whisper) it's like skin against skin. It's better than fine cuisine. It's better than sex! There, now, that's how I feel.

Do you still hunt for obscure singles?

I do. The 7-inch was, and still is, my reason for being. I still collect old 7-inch records, although that’s obviously passing now.

The death of vinyl is one of the saddest moments in pop history. It hasn’t happened here yet, but it’s happened in America, and I firmly believe that CDs are being forced upon us by money moguls who want consumers to have no choice but to buy them because they’re five times the price. But the pop single...

There was just something about the pop single. The two-minute-ten, the cramming of so much emotion into so little time - verses, chorus and fade out. All of the great Elvis Presley singles were under two minutes, and in those two minutes you just felt this tumultuous, massive human sexual emotion.

What about ‘Late Night, Maudlin Street’ on ‘Viva Hate’? That lasted nearly eight minutes.

Not all of them are long. I recall that The Smiths made a record called ‘William, It Was Really Nothing’, which was only two minutes nine. And we were heavily chastised by the record company for doing such a short song because Bronski Beat had released a record that same week which was 13 minutes long. There’s so much to fight against. It’s a terrible, terrible business. I have the bruises...

What do you think of your really obsessive 2 fans - the ones who carry the gladioli about and wear hearing aids and so on?

It makes me feel honoured that anybody would commit so much of their time thinking about what you see sitting before you.

Their fantasies are largely inaccurate, but I obviously can’t visit them all personally, one by one, and straighten things out, as it were. Let’s face it, we all have our fantasies. Most people fantasise about the programmes they see on television, or about sports fixations. There are probably a lot of people who quite like Dan Quayle.

You’ve got no time for the current Manchester bands, have you?

I still do believe that The Smiths were the best. I mean, in the general overview of contemporary Manchester music, examine the success of the Happy Mondays and, well, as far as I know, they’re not successful at all in America. Look at the hysteria that surrounds The Stone Roses and, compared with The Smiths, they don’t have the songs.

None of those groups have the songs or the spirit that The Smiths had, and they don’t present themselves in a new way.

The Smiths were like nothing that had ever occurred before, and that’s a hard thing to do.

What was the secret?

It was a special musical relationship. And those are few and far between. For Johnny (Marr) and I, it won’t come again. I think he knows that and I know it. The Smiths had the best of Johnny and me. Those were definitely the days. Luckily, there’s still more on his part and more on my part to contribute.

It was sad when The Smiths ended, but I don’t think there’s much that...(he laughs) I’m babbling, aren’t I? I’m swallowing my own teeth. It’s interesting to choke on your own words. It must be very gratifying for a journalist to see somebody choke on his own words.

Try again.

I guess, I feel a complete sense of hopelessness about the demise of The Smiths. I think Johnny was very unhappy that he didn’t get an overwhelming degree of attention in the general assessment of The Smiths during their existence. There would be many, many album reviews which scarcely mentioned his name. And I feel that he wanted - that he needed - a stronger platform. He needed to be seen, and that’s been his aim since the demise of The Smiths.

But that’s only one facet. I also think that The Smiths evolved too quickly, too constantly - it just never stopped. It was all very emotional. Constant recording, constant observation, no guiding light at all, no managerial figures, nobody around the group who could offer a really useful, guiding - almost parental-hand.

Johnny, even at the end of The Smiths, was very young. Apart from myself, all of The Smiths were very young. When I first met them they were teenagers and I was 22 going on 23. You know how vast a difference there is between being a teenager and being 22 going on 23? It’s a vast difference. I think The Smiths just snapped due to that kind of pressure, that boring old rock ’n’ roll pressure.

Manchester's changed so much in the last few years - have you anything left to say about the place?

The Manchester landscape has been so overdocumented by me in the past. It’s just so much a part of me and The Smiths’ foundation that I don’t feel I can repeatedly be photographed standing in front of warped signs. I live on the outskirts now. I’m no longer a familiar figure on the backstreets of Manchester. That part of me had moved on, moved away - and happily so.

You really hate dance music, don’t you? Which makes you a real outsider these days...

I’m not so blind as to not be aware of that, but, believe me. I’m happy to be in that category. I could never ever begin to explain to you the utter loathing I feel for, as you say, dance music. I think dance music has destroyed everything. It certainly killed the pop star. It is bought by audiences who do not care about the personalities involved in music making.

I despise the advent of the 12-inch remix, the multi mix, the dance mix, the etcetera mix. It’s all just another nail in the pop coffin.

For people such as I, who don’t take drugs, there’s no way that you could ever become involved in that scene, that you could even understand it.

The structure of the song just doesn’t exist. It’s the basic line of the groove, and that’s all that’s required - along with the high voltage of drug intake. That’s the only experience.

Dance records are generally made by people who are not sensitive, who don’t care about the history of music. And to me that’s the most important element. They don’t care at all about the past. They don’t care about what has gone before.

You don’t see any creativity there at all?

There was an opinion about four years ago that. Oh, isn’t it wonderful that two people can sit in their bedroom in Detroit with a little bit of machinery and come out with this huge wall of sound? To me, that is sterility at its utmost.

I want to see real people onstage playing real instruments - playing them hard and feeling it. I despise the backbone of that dance beat which doesn’t alter at all in the American Top 20. I find it totally shocking and revolting.

What about The Stone Roses? They've cited The Smiths as a key influence and yet you’ve damned the band as a “press creation”.

The Stone Roses are just so press created. The jingly jangly Roger McGuinn-ness of The Smiths was only one aspect of a lifestyle which was multifaceted. And The Smiths made it on their own terms in their own way. Nobody helped us, nobody promoted us, and we didn’t even use video until our ninth single, which was a complete disaster. Up until then it was a private club that, in spite of everything and everybody, became successful.

Do you feel let down by the new Manchester scene?

I feel shuddering disappointment. It’s been entirely embraced by the nation as being the true and real face of-Manchester music, and I can’t recall anything that’s made me feel sadder. Mainly because (a) there are no singers involved, no vocalists with strong tones, and (b) there are no useful lyrical constructions.

It comes down to that boring, turgid, tired, desperate old hat called ‘attitude’. It is pure fashion and pure trend. Sadly, during The Smiths’ existence the music establishment in this country never, ever, ever, under any circumstances, accepted The Smiths. Then, finally, at the time of The Smiths’ death, the country began to look at Manchester as being this hotbed of pulverising new talent. Therefore, all the wrong groups found it very easy to slip through the net and become successful.

Do you ever worry that it could all shrivel away?

I’ve always felt, at each moment, that it could shrivel away. In making 'Viva Hate’, compiling ‘Bona Drag’ and recording ‘Kill Uncle’, there was always a feeling that this could be the final moment.

I think that's something that stays with you forever. You always feel that you’re on the edge - that public taste could go just like that - and then posting letters for a living.

It’s like Ringo Starr making that statement very early on with The Beatles, that if he could buy himself a little shop, he’d be the happiest person alive. And John Lennon saying if it lasted two years he’d be happy.

What would you do if it all ended?

I would absolutely mind my own business. I’d live in a crumbling cottage somewhere in Somerset, out of the way. I would not try to claw my way back. I would not try to reinvent a pop persona. I’m too saddled with dignity to do such a thing. I’m persecuted by a sense of pride and dogged by cunning foresight. It's a shame, I guess - sometimes I wish I was just a simple drunkard.

Comments

Post a Comment