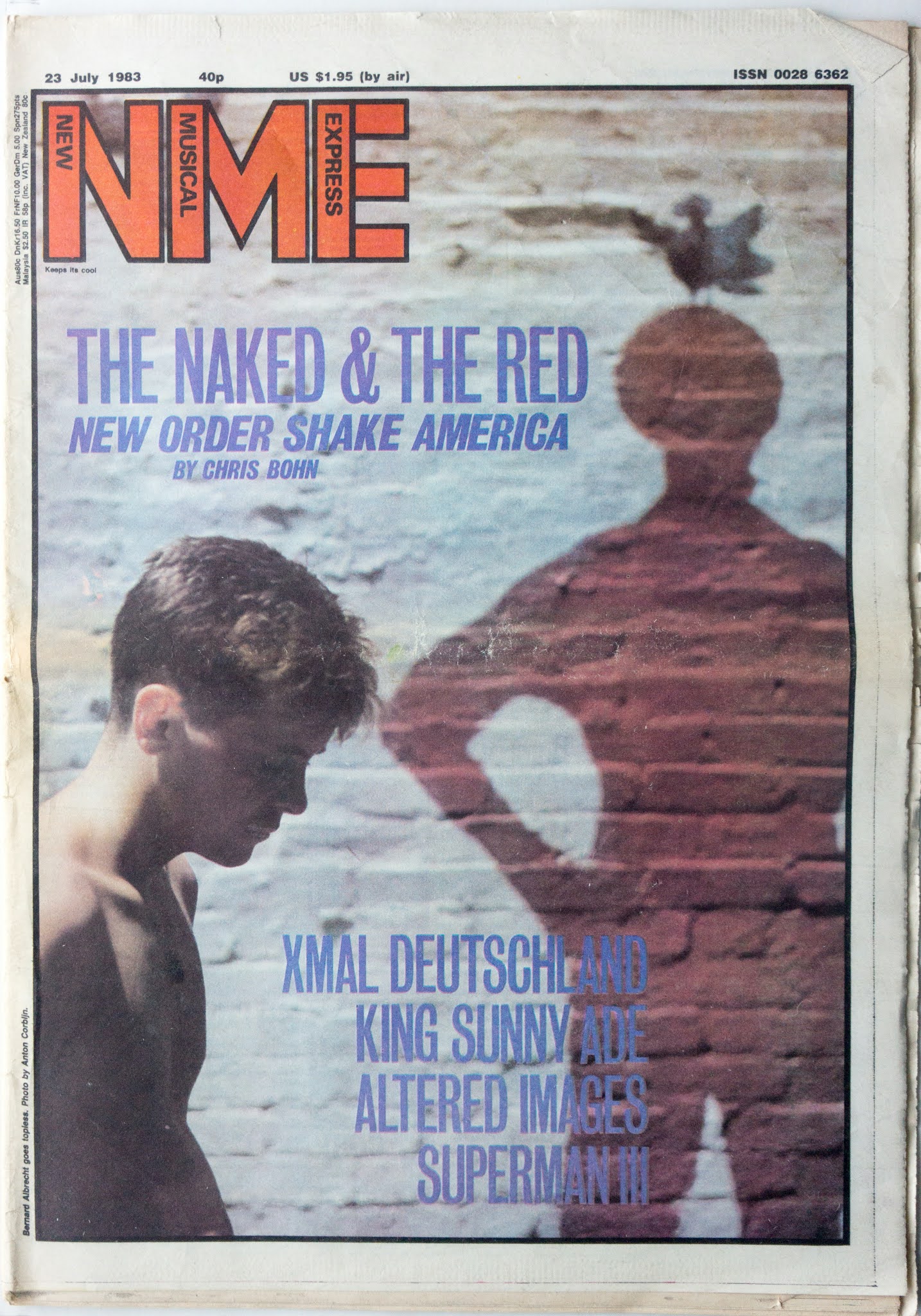

1983 07 23 NME New Order feature

WHEN THERE'S NO MORE ROOM IN HELL

NEW ORDER PROWL THE NEW YORK STREETS

New Musical Express 23rd July, 1983

In the three years since they emerged from the shadow of Joy Division, New Order have become the world’s leading and most wilfully independent group. All without the help of Media “friends”. Now they don’t have to talk to anyone, they’ve perversely decided to open up. This story follows them from The Hellhole of Trenton, New Jersey to The Funhouse of New York, where they’re making a video to accompany their Arthur Baker collaboration.

BY CHRIS BOHN PHOTOGRAPHY: ANTON CORBIJN

SOME PEOPLE try to pick up girls and get called assholes. This never happened to Pablo Picasso. Not In New York.

Visitors to The Funhouse, a Puerto Rican club on 28th Street between 10 and 11, would do well to heed Jonathan Richman's advice.

Pablo's Spanish is the loving tongue here, but really it is physique that talks big with the locals.

Bohn enters through the hideously mocking grin of the giant Joker mask that forms one of its doorways, stumbles through the carny bric-a-brac, feeling like the circus geek, and tries his strength on the test-your-punch ball in club's amusement arcade.

He gives it the best he’s got, yet it barely registers wimp. Fortunately nobody's looking.

So while his luck's holding he passes on the arm wrestling machine and slips back into the crowd. He is hardly less conspicuous among the Puerto Ricans, whose gleaming muscles bulge through T-shirts cut off directly below the chest and shorts slashed at the groin.

"If you're English you don't stand a chance," Simon Topping - ex of A Certain Ratio and presently in NYC studying timbales - has already informed his Mancunian colleagues in New Order. “Ask a girl to dance, they hear your accent, look over you and laugh in your face!“

Anyway, dancing in The Funhouse is largely a solitary pleasure. The most company people ask for is their own reflection in one of the hall's many mirrors. The sound system is more than enough to keep them occupied. The DJ spins fabulously disjointed funk tracks. The nuttier the breaks the better the dancers like them, responding to each echoed rimshot with delighted jerks, throwing their heads back and squealing their heels across the floor to stuttering sequencers.

It is a matter of pride to the dancers that they stay abreast of the mercurial changes.

The Funhouse is where Planet Rocker Arthur Baker comes to test his latest mixes. "He reckons if he can get through to these meatheads he must be onto a winner," goes the local logic.

These early hours he's onto his sixth version of New Order’s 'Confusion' which, when he's finally satisfied with the audience's response to it, will be their next Factory US 12".

As it plays the three boys and one girl of New Order mingle with the crowd unnoticed, checking the reaction for themselves. It is enthusiastic, as indeed it should be.

‘Confusion’ is the result of an extraordinary collaboration bringing together the opposing temperaments represented by New Order's methodical pursue of excellence and Baker’s poltergeist spirit. Though it began as an uneasy experiment New Order rose to the challenge of working at speeds and in conditions unknown to them.

“It's the only time we ever sat down to write," recalls bassist Peter Hook with a shudder. “And God, was it hard! Arthur Baker just stood there staring at us, sort of going, go on go on, write something, and we were walking around in circles thinking, fucking hell, isn't it time to go home yet? We don't normally work well under pressure."

"He’d start a drum machine off and send one of us in saying, have a go on that synthesiser," expands guitarist Bernard Albrecht, nee Dicken. "See what you can come up with. So you're standing there thinking what the fucking hell am I doing? You'd do something and he'd go, that's alright, turn off the drum machine, start the tape rolling and say, right play it again. And even though there'd be a minute's worth of mistakes in it, he'd just say, fuck it. It's alright.

"The one thing he doesn't like about English records, he told us, is they're too neat and clean. And I agree."

It is not out of vanity that New Order are listening to themselves in a New York club at 4.30 am. Having just played the final date of a gruelling American tour in Trenton, New Jersey a few hours earlier, they would rather be back at their hotel celebrating the fact with some sleep.

But even at this hour duty calls. They must film the video for ’Confusion' before returning to Britain, specially as Charles Sturridge, whose previous credits include Brideshead Revisited, had been flown out to make it. Don't let it be said that Factory don't do things in style. (Sturridge was brought in, incidentally, on the instigation of Factory's Tony Wilson. They met at Granada TV, where Tony holds down a day job and for whom Sturridge completed Brideshead.)

At the point of filming, the group still weren't sure of the storyline outside the fact that a Puerto Rican dancer fitted into it somewhere.

Echoes of Fame? Not unless it's at New Order's price...

THE ROCK of America is riddled with bores. It has become such a commonplace activity that talking music here is about as exciting as discussing the weather.

Bohn would be the last person to bring it up, but at every stopping point on his odyssey down Broadway to the Parodise Garage, where New Order are playing their NY concert, he is earholed by a weevil wiv' an anecdote.

The hotel bellhop recalls every blow struck at a Talking Heads concert; a soda jerk gets frothy about all the new English bubblegum groups he's had the pleasure of serving; a cab driver hands him a thesis on how Richie Blackmore revolutionised America.

If in Britain forming a group is - as Julien Temple has said - about as rebellious as joining the army, in America being into rock is on a par with being in the civil service. Being into rock is being part of a non-productive, non reactive glorified fan club there to service the needs of an idol elite.

Anyone tenuously linked with rock - and that can mean as little as having the right haircut and an English accent - has the sort of credit rating that will earn him a free cup of coffee at Bleecker Bob's Greenwich Village record store, so long as he's prepared to put with the world's loudest and oldest juvenile shooting off his latest Weltanschauung.

The clubs provide some sort of refuge from all this mundanity partly because the music is too loud to talkover, but mostly the clubs themselves are so gaudy and great, and the music they play so expertly functional and supremely anonymous that people gratefully use them - the clubs and the music - and move on. Unlike those people who've immersed themselves in the rockpool, they're not overcome with the need to talk about it all the time.

Tonight, however, is not a typical one for the Paradise Garage. Normally a gay black disco, it has been leased at great expense to New Order for the concert. Few of the regulars are evident in the audience, even though the same group is responsible for a stateside - indeed worldwide - club hit in 'Blue Monday'.

The slyest, most perfect, driest and most sexual of dance records, 'Blue Monday' is a model of anonymous functionalism, the work of a group who assert quality above novel identity.

And you can't believe how refreshing that is until you've heard any one of a strewn of British hits screaming "love me, love me, love me!" from every Anglophile store, radio station or club.

Nevertheless, despite themselves, New Order's concert draws an audience in awe of the group's name and reputation, based on the impressions they got from reading the British music press. They are at once given a lot to live up to and even more to live down ...

"What people write about us is usually five miles wrong!" mutters Bernard ruefully.

"All these Americans know all the stuff, but all they do is stare," says Peter Hook at once flattered, frustrated and flabbergasted by their American experience.

"It's really weird. The first half dozen gigs before we got to New York we went down pretty well - a bit too well. It was like they were just waiting for us, we didn't have to win them over or anything. We'd already won. All we had to do was play. They were all shouting 'Dreams Never End'! 'Ceremony' - just like they do in Britain. At least we've had some lively over the top audiences there, but here the only lively audience we've had was in Austin, Texas. Otherwise we haven't had to struggle, meaning there's no point to doing it really.

"Preaching to the converted isn't any fun is it?"

That's as maybe, but it doesn't take long before American audiences become slightly unsettled by what they're seeing.

Brought up on the New Order mystique as fostered by the British music press, their reverence is duly shattered by the group's offhand and nonchalant stage manner, the long pauses between songs and maybe even the summery sight of Bernard Albrecht in grey shorts, looking like nothing if not a devilish choirboy. Once the music starts sinking in, it is obvious, too, that this isn't the same group who made the heavy emotional demands of their first LP 'Movement' and their early singles.

It is as if they've digested the darkness and rigour that informed those great, albeit gloomy records and no longer feel the need to bludgeon people with their seriousness. That period still informs the present New Order, but in the interim they've become tighter, freer and extraordinarily playful; which isn't to say they're any the less affecting, just that they now touch a broader spectrum of feeling and experience.

New Order have become a truly fearless group, one that refuses to be intimidated either by their peers' trends or the desires of the audience. They will take you - if you're prepared to let yourself go - from the swollen heartbleed of 'In A Lonely Place', through the impishly turbulent 'Temptation' and slamdance of 'Confusion' and onto the entirely different joyous plane of most of 'Power, Corruption And Lies'.

Within the framework of one song — such as ‘Your Silent Face' — they’ll couple the banal and comic with moments of true beauty. The song is hooked into a stunningly simple and subliminal sequencer pattern that serves as both rhythm and melody; it is topped with a ridiculously insipid OMD type synth tuna, which would have spoilt it, had it not been rescued by Bernard'a gently spiralling ocarina. The words follow a similar trajectory - one moment reflective, the next hilarious. Could you imagine the old New Order so carefully drawing the listener into a tissue thin web of sensitivity only to abruptly eject him with the kiss off lines: ‘The sign that leads the way/The path you cannot take/You've caught me at a bad time... So why don't you piss off!"?

If any song marks the lucid New Order, it is that one. Where the early records were written under the shadow of Joy Division the songs from 'Temptation' onwards feel looser, more natural.

“Well when we first started, I tried writing serious lyrics and I was just shit at it,” remarks Bernard candidly. “So for the second LP I just wrote down whatever I felt like. I didn't really care whether the lyrics were good or bad on the second one so I was more relaxed.

“On the first one I felt so selfconscious because I was coming after Ian, who was such a great writer. I wanted the lyrics I wrote to be good. They were alright, but they were not wonderful. After I'd said, fuck it, I started to enjoy writing a lot more. Ironically, the songs on the second LP mean a lot more to me. And because they re less selfconscious, they're more truthful to myself.

“With ‘Your Silent Face', well we wrote that one in the studio. Because we wrote this very beautiful emotional music, we thought to put a beautiful very emotional vocal line over the top was a bit obvious. So we put down a quite nice vocal line and some nice lyrics, but by the end we got stuck for a couple of lines.

“Everyone was thinking of really beautiful, poetic, meaningless lyrics. Then I thought, instead of having something beautiful, poetic and meaningless, we might as well have something dumb, idiotic coarse and meaningless. An absolute contrast to the rest. Even roses have thorns...”

THE FOUNDATIONS of America's Rock, based on a fake bonhomie, Boy Howdy beer and cheesy McDonald's grins, are easily undermined.

The New Order Way of doing things makes them quake a little, not because it's calculated to, but because their genuinely casual approach, often at odds with the highly disciplined music they're playing, constantly disrupts the mood of the night. Some interpret their laconic, incommunicative stage demeanour as arrogance. Others think it’s funny. A worldwide complaint seems to be that

their sets - at around 45 minutes - are too short.

“Usually we're not contracted to play a specific time, so we come over here and play a set which we think is long enough, but not so long that we get bored," explains Peter Hook. “But everybody seems to think it is too short, I don’t know whether that's a compliment or not!"

“We play 45-50 minutes because it feels right to us. We almost caused a riot in Rotterdam once. The promoter gave out notices warning that this band only plays 45 minutes, so if you don't like it don't come in!

“That we don't play encores is another big beef with people. Once, just as an experiment, we played seven numbers, went off, came back on and played three more. We played our usual ten numbers, but because everyone thought we'd done an encore they weren't bothered!”

Not everybody’s so easily pleased, as Bernard recalls with a smile.

“One kid in Sheffield a couple of years back said, you didn't play such and such a song tonight and you only played for 45 minutes. You've shattered all my dreams. Give me my money back! Fucking hell, I almost bottled the bastard! And he said, me three other mates would like their money back aa well!

“I dunno,” he expands, “we shouldn't really categorize people I suppose, but I know the type. We have the studious type with glasses and a fringe and we have the nasty little men with chips on their shoulder type who do that sort of thing. And the kind of people who have just read about you and expect you to be exactly what they've read.”

"There's a lot of nutcases who buy our records I can tell ya,” says drummer Stephen Morris, “who come backstage after a gig.

You know: why didn’t your play any Joy Division songs? Why did Ian Curtis kill himself? Some get really worked up about it.”

Or they come in and tell you, you’re a load of rubbish, you are,” chips in synth operator and second guitarist Gillian Gilbert. "Imagine! It’s like if you were in a pub and somebody said, you’re a load of rubbish you! You’d flippin’ hit them round the ear’ole. But you’re supposed to just sit there...”

"Or go, oh yeah, you're right," mocks Steve. “Soddin' hell. Fucking hell, I should give it up now”

Later Bernard tells Bohn the biggest mistake people make about them: “Thinking we’re serious. Because we’re serious about the music they think we take everything seriously. Like, the other night a kid came backstage after the gig and asked us to sign an LP. Hookey told him to shove it up his arse. We were only Joking, but because it’s us he took it serious and went away hurt.

“I dunno,” he sighs. “They take everything you say so seriously, as if you mean everything..

BERNARD BREEZES in to the breakfast room of the Holiday Inn, tired yet affable as always. He takes a long sigh, “fooKINell!” by way of morning greeting and proceeds in his quiet spoken Lancashire burr of a voice and with a gleam in his soft eyes to relate various anecdotes and pranks that have occurred during the tour.

The most unlikely concerned a 65 year-old stringer for a German teen magazine based in LA. He wanted the group pictured in Micky Mouse ears! Surprisingly, only Bernard refused.

“Then I made the mistake of sitting in the pram we use to push around the video equipment,” he laughs, “and while I was jammed there he rammed the ears on me head and took the photograph!”

Another night the group’s highly unconventional manager Rob Gretton tempted the lighting man with 100 dollars to join New Order onstage and sing for one number.

“He stood there with the lyrics to ‘Cries And Whispers’ shivering like crazy. You could hardly hear him!”

The best and cruellest prank, however, took place at London Brixton and involved Joy Division biographer Mark Johnson, an American who dogs New Order’s every move. At their recent Ace concert, they got the number of his ’bike announced over the PA, saying it was blocking an entry. When he rushed out to move it, he saw New Order’s roadie van hurtling up the road with his ’bike lashed to the top.

And there you were thinking that The Stranglers were the bad boys of British pop.

PERHAPS BEFORE New Order depart NYC for Washington DC, we should brief the President about the group.

New Order are the phoenix who rose from the ashes of Joy Division, from Manchester, who were the last popular group from Britain to probe heart and soul with stark candour. They never attempted anything so conceitful or deceitful as writing anthems for doomed youth, but the rigorous explorations of self, as personified by vocalist Ian Curtis’s words, were uncannily right for the moment.

After Ian killed himself and Joy Division as such no longer existed, popular music took fright and for the large part regressed into its present state of mercantile infantilism, as if nobody wanted to take the risk of running so deep again. Thus phun became the dictate of the day, a pervasive cynicism gnawed away at any ideals that survived punk - to an extent a necessary stage in pop’s sweet growth - and business acumen became the ruling aesthetic.

The greyly unimaginative post punk Indie boom wasn't particularly encouraging to the independent cause; and because the media is only capable of operating in terms of epic sweeps, they swept out the imaginative and inspired along with the rest

The three surviving members of Joy Division, meanwhile, auditioned a new singer but, finding no one suitable, brought in untutored musician Gillian Gilbert - Steve Morris' friend - and renamed themselves New Order.

How about an introduction to yourself, Gillian? She is, incidentally, an attractively down to earth and funny Mancunian who has the sort of accent that explains John Cooper Clarke's popularity.

“I vaguely knew Joy Division,” she whispers. “I used to rehearse next door to them in Manchester when I was in a punk group, just before their hit I used to go and see them and then I got to know Stephen - I sat next to his sister In geography, which is a coincidence really. Ha ha. I think it was one night at Liverpool Erics and Ian had hurt his hand on a bottle or something, so he couldn't play the guitar for one number. It wasn’t a very big bit, so as I could play guitar a bit, I played that one number.

“Then, some months later the others called me. I think they wanted someone without any knowledge of guitar whatsoever to remind them of when they started and couldn't play. I think they were also looking for somebody who didn’t have any particular style, so they could work them better into the band.”

“We didn't really want anybody who could play,” Stephen concurs. “If we got someone who could he might not fit in with the way we write songs and stuff, so we decided the best thing to do was get someone in fresh. Gillian was the only person we knew who couldn't play. We’d seen her play before and she definitely couldn’t!”

They spent a year writing and rehearsing a completely new set retaining only two unrecorded Joy Division songs - ’Ceremony’ and ’In a Lonely Place’ - which they released as their first single.

Anticipating the intense media interest focused on their return, they sensibly avoided its glare. With admirable perseverance they stuck to their own way. Being a sensitive collective beast the media took New Order's unwillingness to cooperate personally and thus had them and Factory - the Mancunian independent they’d allied themselves to - figured as hostile, sullen and incommunicative.

The lack of exposure hasn’t harmed them any. Through a series of infrequent international tours and the odd date at home, they’ve become the best selling independent group in the world, racking up club and radio hits in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Europe and America.

That they’ve done It their way - that is, with a minimum of fuss and the emphasis on quality, not personality - is something they quietly cherish. Even if it has meant odd interpretations of the New Order silence.

"I just don’t think the group should be at the forefront,” asserts Peter with some authority. “I don’t think we’re that important. If we’ve got something to say, we say it. If we haven’t got anything to say it doesn't mean we're dumb. It just means we don’t fancy shouting our mouths off, or something like that. But I consider the music very important because it affects me, so I don't see why it shouldn’t affect other people as well. I find it exhilarating, depressing, happy, sad or whatever. I just don’t think our personalities need to be pushed.”

The seeds of their mistrust of the media were sown when they were still Joy Division.

“In the very early days before ‘Unknown Pleasures' the music press detested us and that was a kind of driving force to go on,” says Bernard. “When ’Unknown Pleasures’ came out we were suddenly wonderful. We went from being the most unpopular group in the world to the most popular. Fucking ridiculous!

I remember reading one live review of a gig at the Moonlight Club. We played three nights there and got wonderful reviews from all of them, even though one night we were shit, really bad. And the review from that night said, this group was so good they made me want to piss in the face of God! And we were fucking appalling! When I read that I just thought the whole press thing with Joy Division had gone completely over the top.”

Shy and conscious of their own privacy, they stopped doing interviews three years ago. Most importantly they didn’t want to get sucked into the music industry mainstream.

Says Bernard: “We were worried in case once you started you would begin to do things the way everybody else does and that would have been boring. So to keep our noses clean ... It’s been pretty enjoyable the way we got where we are today. It’s been realty good the way we’ve done it because we've not gone through the system and I, for one, feel better for it. I don’t mean because I've done things honestly. I mean, each to his own.”

From the distance they’ve so admirably maintained from the pop maelstrom, its absurd manifestations must appear ridiculous. From the other side, the constancy of New Order and its Factory allies might be mistaken as old fashioned or slowwitted.

“I think this idea of being hip or not being hip is a fucking load of shit,” Bernard forcefully states. “It’s a trap that music has got into. If you see the progress of music as a maze, well now it has arrived at a dead end. The idea of hip has stopped people expressing themselves as much as they should do, because they're afraid of not being hip. Like, you can only be hip if you’ve got this rhythm or these instruments, otherwise people will stop listening to you!

“I think it’s terrible because it's stopped people producing music unselfconsciously. They're too conscious of whether what they’re doing will fit into the mould or not. Hip is making a lot of people very narrow minded. Hip is like a chain reaction. A music paper gets very narrow minded in its approach, the people who read it get that way and eventually it works its way into music. Then everything starts going in one direction. The music scene In England now doesn’t allow for any kind of fringe to be successful.”

THE ONTARIO cinema, located in one of Washington’s black districts, specialises in lurid Spanish pictures. But tonight they’re featuring New Order. That is, if they arrive.

Bohn and Corbijn travelled down from New York in the relative splendour of an Amtrak train, passing through the Baltimore of Diner, Philadephia and across the Delaware. Shortly before Wilmington the train pulls up outside a plant called Destruction Of Confidential Records. Bohn ponders whether he should throw in his notebook, but decides that no guilty secrets are contained therein.

So much of what New Order says is good sense and the way they've ploughed their money back into Manchester by way of The Hacienda club is exemplary. Their attitude ought to serve as as a strong example in these times when popstars would sell their soul for a line - preferably on a mirror but otherwise in a teenzine. Not to mention the nobility of their art; he is pleased to publish it.

The group travel down by air shuttle, arriving at Dulles (“’sDullesfuck!” sneers Simon Topping, who is guesting with the opening act Quando Quango) Airport. Half an hour before the show is due to begin Steve Morris, Peter Hook and manager Rob Gretton are still missing. Quando Quango, also a Factory act, are sent out to appease the restless audience with their stylishly aloof and bemused funk.

It works fine, but the four songs they’ve brought with them don’t last long. In the meantime the three have arrived “ratarsed pissed” on melon ball cocktails. Hookey immediately falls asleep under a dressing room table and later melts into the night.

He’s still playing hookey when the group, already hours late, must go on. They start without him and try to pass off Rob Gretton as the Third Man, but even from the back it is obvious that this figure in drooping tracksuit vest and shorts flailing away at the cymbals, often as not missing them, is not the right man.

Midway through the second song, Hookey shows. “Ah, the black sheep returns,” mutters Bernard, while shooting Hookey a rueful glance. Hookey straps on his bass, looks out into the audience and apologises: “Hi shitheads!”

A new order: being pissed means never having to say your sorry.

TO COMPENSATE a new, healthy Hookey arrives first in in Trenton, New Jersey. Hardly a prestigious finale to the tour, it is a godforsaken, rundown place, the equivalent of a northern milltown after the mills have closed down. The venue is once again in the black quarter.

Next door parents are holding a carnival to raise money for the baseball Little League. It is here New Order go for a photo session, gathering in front of something called The Hellhole.

What's on the other side?

“A vision of what’s to come for them's that misbehave,” pronounces the ticket collector.

Duly warned, New Order stop squabbling over who should wear the funny glasses and line up for their portraits.

Bergmanesque visions of the grim reaper no longer hover behind the music of New Order. Cries and whispers have transmuted into smiles on a summer night.

New Order have struggled with the Meaning of Life and come out winning.

Comments

Post a Comment