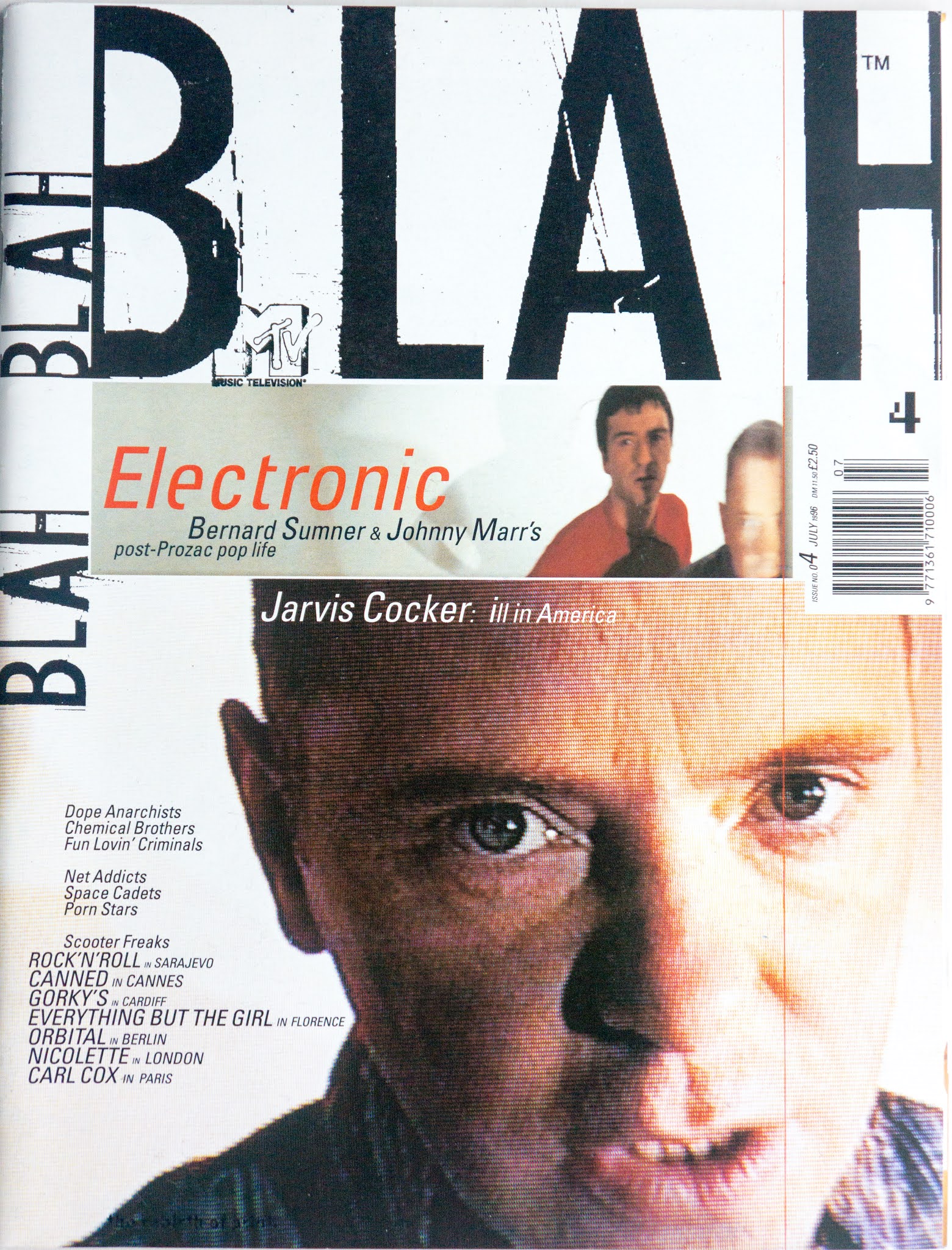

1996 07 Electronic Blah Blah Blah

Johnny Marr

Bernard Sumner

Brothers of invention

Separately, they were the architects of some of the greatest British music ever made.

Together, they’re trying to do a bit more than that. Ladeez and gennelmun, cleaned-up, wised-up and trussed-up in some nice Safeways pants, the supersonic duophonlc Johnny Marr and Bernard Sumner.

On the first faintly warm evening of the summer a spacious, snow-white, chauffeur-driven Mercedes sweeps through the streets of central London. Inside are Electronic, Manchester's coolest dance duo, en route to Holland Park's upmarket celebrity diner, Daphne’s. Lounging in the back seat, Johnny Marr, former Smiths guitarist and one half of the band, recalls how, the last time he ate in Daphne's, he sat next to Al Pacino.

Marr recounts how he eventually persuaded an anxious Pacino to give him his autograph out in the street. Sitting in the front seat, meanwhile, sometime New Order singer Bernard Sumner reckons his current musical partner left with the actor's style as well. Or is it Ian Broudie's? Sumner isn't sure.

“Try on your shades, Johnny," he urges, "then I'll know for certain."

Despite a distinctly muso media image, Electronic take themselves far from seriously. Sumner declares that he'd rather discuss his underpants than the band's new album.

“I never wear under underpants, you see, ” he reveals. "Why not? Because the ladies don't like it. Now that we're doing photo shoots, though, it has become a bit embarrassing. You know, when I'm hanging out in the changing room. So I bought a red pair at the weekend. Except I got them in Safeway and Johnny's absolutely disgusted that I didn't go to Calvin Klein. You're appalled by my underpants, aren't you Johnny? But now I've found out that I should have bought a string pair, because apparently the holes in them keep you warm."

"Oh my God!" exclaims Marr, “don't you bloody dare."

Would you rather he didn't wear underpants at all?

“Yes. I mean, I don't care what he wears, as long as he keeps them well away from me. ”

"Ah, that's it isn't it Johnny? It's not that you're disgusted by my choice of underpants, you're actually upset because I've started wearing them..."

It’s hard to know what to expect from either of Electronic. So much has been written, rumoured and assumed about both since their respective bands became the two hippest British guitar acts of the ’80s. Sumner has tended to be portrayed alternatively as a pissed-up party animal or a shy and sensitive poet. Likewise, Marr has come across as both a big-headed guitar obsessive and a moody cocaine monster. Together, they could prove to be either a pair of self-important rock stars or, worse, lads.

In fact, this evening at least, none of the above apply. Both are relaxed, easy-going and good fun. They take the piss incessantly out of each other, and recount a series of entertaining rock’n'roll stories with a dry, down-to-earth sense of humour.

Tonight Electronic are set for a quiet meal out in London, before heading off to the countryside early in the morning to shoot the video for 'Forbidden City’, the first single from their second album, Raise The Pressure. Since the release of New Order's Republic in 1994 and the subsequent tour, the pair have spent two years together, ensconced in Marr's studio in Manchester, recording the follow-up to their self-titled debut. Released in 1991, Electronic, a slick and seamless mix of muscular dance rhythms, effortless melodies, Balaeric beats and Sumner's trademark laconic vocals, not only provided Marr with his first solid writing partner since his acrimonious split from Morrissey, but also offered Sumner an easy escape from his long-term commitment to Factory's finest. A slew of singles — 'Getting Away With It’ [featuring the Pet Shop Boys], 'Get The Message', 'Disappointed' and 'Feel Every Beat' — eased their way into the charts over a 12 month period, while the album itself went down as one of the best British pop LPs of all time.

Five years on, Electronic have learnt how to infuse their minimalist sound with soul [thanks to collaborative help from the likes of former Kraftwerk keyboard player Karl Bartos, Black Grape cohort Ged Lynch and Primal Scream singer Denise Johnson], how to handle personal relationships and, most importantly they insist, how to make music without the aid of artificial stimulants.

“Apart from using different equipment to update our sound,” begins Sumner, "the biggest difference with the new album is that we recorded it during the daytime. For the last one we'd start at four in the afternoon, work through to six in the morning, and get completely fucked-up every night. This time, we were barely fucked-up at all.

“When I'm out of it I write on my instincts. I drown my conscious brain in substances and let my subconscious do all of the work. It's so much easier. Everything flows and you always end up with something good. But it made our lives a misery. It was impossible to integrate with the outside world. Plus, we wouldn't see any daylight so we'd end up wigging out.

"I had to re-educate myself to write when I was straight. That's basically why this album took so long to make. It's a completely different process writing lyrics at one in the afternoon than at two in the morning.

If I've ever managed to write at that time of the day before, I was well fuckin' off it! When I tried to write sober for the first time, it literally felt like someone had dropped me in a vat of cold water. It was a total shock, but I wanted to rely on my intellect instead of my instinct for a change. I felt like throwing away the crutches would be a way of growth."

If Sumner, almost as well known for his rock'n'roll excess as his ambiguous lyrics, sounds as though he may be getting old, bear in mind his recent, well-publicised stint on Prozac, the fact that he remains a regular at his local club, The Hacienda, and that, by all accounts, he still drinks Pernod by the bottle. He has, however, decided to slow down. It was at the tail-end of New Order's Technique tour of the States in the late '80s that Sumner first became conscious of his health.

“It sounds ridiculous," he says, “but that turned out to be something like the fourth highest-grossing US tour of the year. New Order had literally become this great big money-making machine, and once you're on that roll, no one wants it to stop. Not even when it was obvious that my health was suffering. I ended up in hospital in Chicago and a gig had to be cancelled — the only New Order or Joy Division gig that ever happened to. I was incredibly ill and it suddenly made me realise how important health is. My whole family—parents and grandparents — suffer from very bad health, so I've seen what it can do to people when they get older. All the money in the world isn’t worth fucking yourself up for."

Subsequently, Sumner returned to Manchester, decided to take a break from New Order, and invited Johnny Marr to join him in Electronic.

"For me," says Sumner, "Electronic was about taking time out to assess myself as a musician. Ever since 1977 and Joy Division, I had been writing and gigging non-stop. Just for a change, I wanted to drive the bus instead of being dragged along by it.

Sumner first worked with Marr, albeit briefly, way back in the early '80s, when the pair helped out DJ Mike Pickering [now the "M" in M People] on his obscure jazz-funk Factory act Quando Quango. Later, The Smiths and New Order would occasionally play on the same bill, both bands shared several crew members and, inevitably, met each other out and about in Manchester.

Marr, who, since splitting The Smiths in August 1987, had played sessions with Bryan Ferry, Talking Heads and The Pretenders, not to mention becoming a semi-permanent member of The The, agreed almost immediately to Sumner's offer. Exactly 200 days later, with a little help from Neil Tennant, 808 State and assorted Mancunian clubbing mates, the first Electronic record was written and recorded.

After almost two years of promotion, some American stadium gigs supporting Depeche Mode, and a brief British tour, the party was over. Bernard Sumner returned to New Order to make the ill-fated Republic, while Johnny Marr went back to The The to record Dusk.

’There was never a shadow of a doubt that we would do another Electronic album, though,’ insists Sumner. “Had we not both been tied to previous commitments, we would have started on it straight away. “

Unlike Sumner, however, Marr decided not to tour with his project.

“I got to the stage after the last Electronic album where I realised I had literally been on a quest from the age of 14," says Marr. “I have an insane drive for music which is vary useful, but I needed time off to find out why I had that drive. Luckily, that coincided with my two kids being born and Bernard recording Republic. I'm so glad that I took time out before this album. I love making music, but it’s easy to forget why you're doing it and what you enjoy about it."

Marr attributes his new-found ability to handle being a band to his relationship with Sumner and experience with Electronic.

“I'm still totally obsessive about what I do.' he says, ‘but now I've found the best way to work is to switch off sometimes. Other people I've been in bands with would grumble if I wanted to do that but Bernard encouraged me. We spent 12, sometimes 15 hours a day, every day for two years working on the new album. But whereas before, all I would have been concerned with was the music, this time I also considered my family. I could still go three or four days without seeing my kids, but at least now I've moved a mile down the road from the studio, instead of actually living in the same building. “

Just months later, it was Sumner looking to Marr for support when the recording of Republic started to go horribly wrong.

"Republic was a very hard album to make," recalls Sumner. "The financial situation when Factory went bust became very complicated and working with a producer for the first time since Martin Hannett was also quite hard. There were numerous internal political differences, too. Every member of the group was pulling in a different direction. I said at the time that it was like pushing a car with the handbrake on and I stand by that statement. Johnny was nothing but encouraging throughout that entire period. He used to come to the studio regularly. It made me feel that at least somebody was on my side.

"Then we went and did lots of gigs. Well, 13 gigs, actually. The idea was to do one gig for every track on the album but the bastards tricked me. The rest of the band—the cads — never let on that there were actually only 12 tracks on Republic. After that tour, I had to go on holiday to recover. It's not that they weren't good gigs, apart from the last one in Boston, but I ended up really sick again."

Sick from what?

“What do you think? Overindulging at the gig before, which was in New York. Actually, it wasn't just that. At the same time I had this weird virus in my stomach that occasionally flared up — basically if I drunk too much Pernod — which made me terribly ill for 12 hours at a time. I couldn't sit up or anything. I'm completely cured of it now, but it was always a real problem when we were on tour. The thing is, I can't be phony. If I feel shit I'll play shit. I can't pretend anything I don't feel. I'm afraid I never went to drama school. ’

“Bernard," interrupts Marr, “feels like he has to be in a shamanistic-type trance to play in front of an audience. It's true. It's also very noble. I'm sure it's because most frontmen in bands have always wanted to act it up and be in the limelight whereas he's in the unusual position of ending up as a frontman almost by default. He doesn't have that deep-seated desire to perform that most singers do. The vast majority of frontmen only really come alive in front of an audience. “

The combination of both Sumner and Marr's experiences since the first Electronic album has clearly brought them much closer together, personally and professionally. Sitting side by side in the restaurant—their casual, dressed-down clothes starkly marking them out from Daphne's regular cocktail crowd — they are incredibly comfortable as best friends. They eat food from the other's plates and each quietly praises the other whenever one is away from the table.

“I see Bernard more than anyone else outside my family,' says Marr. “When one of us is going through something in their life, usually the other is, too. I mean, when I got into running and working out, Bernard did too. When Bernard got into going away sailing, I did as well. We're definitely friends before anything else.

"Plus, we're both obsessive about making music, but we've also both been in this business long enough to be objective. Unlike most musicians, we realise that a problem with a song is not the end of the world. That's why we've never fallen out in the studio. We've even started to think in unison."

The pair claim they now work so well together that, for their next album, they may abandon their original intention of always bringing in new musicians.

"Electronic was conceived as a trio," explains Sumner, "with the third member constantly changing. We felt that a strict group structure always comes up against a brick wall eventually. Our way, each time we made a record, the entire chemistry of the group would be different.’

On Raise The Pressure, Karl Bartos — whom Sumner met through a mutual friend — is credited with co-writing six of the 13 tracks, including ’Forbidden City' and the scheduled follow-up single, 'For You'. Sumner, however, maintains that—bar the absence of stimulants—his [un]usual writing process remained unchanged.

'To write lyrics,’ he explains, "all I’ve ever done is listen to the music, which immediately inspires me. I'm a very visual person. Even as a kid, I thought in pictures, never words. When I listen to a song, scenes come into my head and I start coming up with characters.

"As soon as I heard 'Forbidden City', I pictured a father and son. The father is a drunkard who beats up his family, but the son can't shake his instinctive, emotional tie to him, simply because they're family. I didn't know that's what the lyrics were about when I was writing them. It wasn't until I read them afterwards that I realised. To be honest I've no idea how I do it. I don't want to know either. That way, every time I write a song, it'll be something fresh.

"The track 'Second Nature' is totally autobiographical. It's about where I come from, where I am now, and the attitude that has left me with — which is, that no matter what you do, the world will keep on turning and if you don't do anything, it'll just carry on without you. I've realised that if you don't grab the world by the bollocks, the world will grab you by the bollocks — underpants or no underpants. ’

On the first Electronic album, Sumner claimed that several of the tracks were, unusually for him, about social issues — whether gang violence in Manchester or the unstable political situation in Russia. Are there tracks like that on Raise The Pressure?

“I'm an only child, ’ he says, "so I grew up looking at myself because there was no-one else to look at I used to lie in bed at night for hours, just thinking about myself. That's why most of my songs are about me, me, me. Very occasionally I realise that could be a problem, so I purposely look at what’s

happening around me. Although I’m rather wary of that in case it looks like I've just picked up a newspaper and ripped off a story. Of the new songs. 'Visit Me’ isn’t about my life. It's about a murderer. I attempt to get inside their mind, to study their conscience after they've killed someone. ’

While both Marr and Sumner insist that they meticulously attempted to erase any ideas which surfaced on their debut album, Raise The Pressure — despite boasting far more of Marr's innovative guitar — clearly shares Electronic's sparse electro and softcore American rap influences.

'When we started recording, ’ remembers Marr, "both Bernard and I were heavily into an album called One by Me Phi Me. It's a very melodic American rap record, set against acoustic guitars. As time went on, we listened a lot to MC Lyte's last album, as well as EPMD, Funkdoobiest and Queen Latifah. I really got into women rappers. They're much more melodic than a lot of the men who just shout in your face.

‘We were also influenced by the records we were hearing at the club Flesh at The Hacienda. The tracks ’Dark Angel' and 'Until The End Of Time' came directly from those nights. Towards the end of the album I got really into Inner City's last single, 'Your Love', and Ennio Morricone's Usual Suspects. Most of all though, I became obsessed with the first Mantronix album. I wanted to do some tracks that were in the style of early New York electro. Really pure, but not at all muso.

"It doesn't matter to me that a lot of that stuff is quite old. Anyway, midway through making the album, there was this movement in some of the clubs where all those electro records became quite hip. Not that I care what's hip. I'll happily hold up my hand and admit that I still listen to old Mantronix records. It's sure better than digging out the fuckin' Kinks and calling it your own."

"To be honest" interrupts Sumner, 'we're not really influenced by any new records because after we've been making our own music for 12 hours a day, the last thing we want to do is go home and listen to someone else's. I'll either watch TV or go to a club. But even in a club, I don't really listen to the songs. I'm usually off it which means I'll dance to anything with a 4/4 beat.

'I go to clubs for the atmosphere or to hang out with my friends. I want my concentration blown away. I want to forget everything. Oh God, it sounds like Saturday Night Fever! No, really, if I hear a record I like, I want to enjoy it as a punter, not as a trainspotter or a musician. I certainly have no desire to start noting down what's on the turntable."

'Karl was useful for that though,’ adds Marr. 'I have to admit, I'd occasionally get him to note down a beat at Flesh. Karl is incredible, he just whips out his pen and we've got it. Honestly, he can write any tune down in musical notation, then go back to the studio and programme it into the computer. ’

Can't either of you do that?

Electronic look bemused.

"What?" asks Marr. “Us, write down music? Can we fuck."

Despite their position as two pop-cultural heroes, steeped in the traditions of British electronic and guitar music, Johnny Marr reckons that neither he nor Bernard Sumner "fit the cultural stereotypes associated with contemporary rock or dance. We're certainly not Britpop lads, nor are we pretentious types. I'd call us lads who are interested in artistic endeavour — whether that would be something in graphics or a Phil Spector sound.

When I was a teenager, I'd be listening to serious, intellectual rock records one day, then something like Chic or early 12-inch disco singles the next.

'There's a lyric in ‘Dark Angel' that goes, 'Don't think about it, let me take you out'. Bernard describes it as being about nothing but I think that line is fantastic for exactly that reason. It's a million miles from muso but probably a lot harder to get just right. Madonna writes lines like that brilliantly. That direct message of having a good time without being inane about it is the whole essence of dance to me. All the flirtation in nightclubs, even the getting ready to go out or buying good clothes. It's as far removed as you can get from sitting about at home, getting stoned in front of the telly."

"Of all the new British bands," butts in Sumner, “I'd rate The Prodigy over any of the Britpop lot. I reckon the popularity of retro-rock at the moment is simply people reviewing the millennium. Whether we like it or not, the success of Oasis is a fact of life. There's no point getting depressed about it because you can't do anything about it. It's like the weather. I mean, we've just had a terrible couple of months thanks to freak weather conditions. But I can’t control that—just like I can’t control what records the public want to buy. All I can hope is that the climate changes bloody soon, 'cos we’ve had really shit summer so far."

"The biggest problem," says Marr, “is that we really go out of our way not to be anally retentive about the music — believe it or not — and we certainly don't make records for other musicians. Suddenly we found that a lot of the people around us were doing exactly that. The video directors we've worked with were trying to make clever pieces of art to impress other directors. Most of them were total wankers.

“Sleeve designers tend to be exactly the same. One guy we didn't end up using came up with a design for the new album that was just plain black. How crap is that? All we could see was Spinal Tap, but he had this whole pompous, intellectual design theory worked out. He told us that it wasn't just a black sleeve — it meant something more. We said, 'We don't like it'. He said, 'Oh, you just don't understand. You don't get the joke.'

“It's not as bad as what Bernard said about the Oasis sleeve, though. We were in this studio in Manchester with Oasis when the guy who does all their artwork came in with the finished design for [What's The Story] Morning Glory? It was the first time anyone had seen it and he was really nervous about Noel's reaction, but also really proud of what he'd done. Bernard, who had been out of the room for a second, came in, took one look at it and said to Noel, 'Oh my God, that looks like something you've knocked up yourself.' The guy was devastated!"

They're having dinner and having fun. Even before they embark on the round of video shoots and promotional chores, even after such a long lay-off from the rock-celeb hoopla, Bernard Sumner and Johnny Marr are even talking about taking Electronic out on tour.

“I'm quite up for doing some gigs again," says Sumner, “mainly because I'm so proud of what we've done as Electronic. If we do play though, I'm going to do every concert straight and not get fucked up, the same way we did the album. It'll be the most nerve-wracking thing I've ever done. But getting fucked up on tour became a way of life that almost took my life, and I know now that it's too valuable to destroy like that.

“I'm not going out on any mega tours, though. Those huge tours even got to The Beatles — and Jim Davidson. Sorry, not Jim Davidson, Jim Morrison. I'm a composer, not an orchestra. I like doing things that are creative, like writing music, not things that are reproductive, like playing the same songs over and over again.

“Wait a minute!" The old New Order boy looks at Johnny. “I've just thought of one reproductive thing I quite like."

“Yeah?" says Marr.

"Well," nods Sumner, “let's just say it involves Safeway's underpants..."

Comments

Post a Comment