1987 09 26 Morrissey Melody Maker

HOW SOON IS NOW?

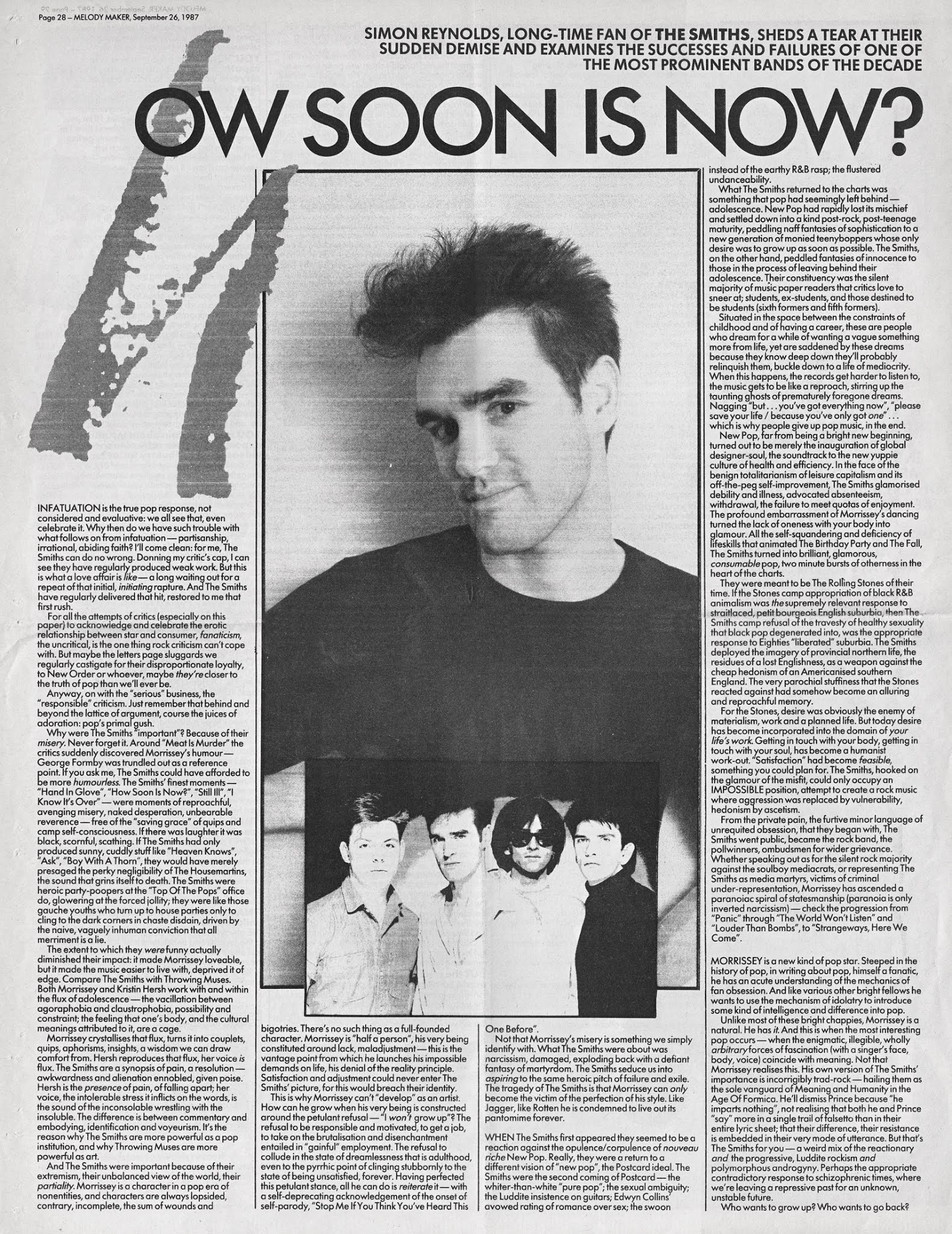

SIMON REYNOLDS, LONG-TIME FAN OF THE SMITHS, SHEDS A TEAR AT THEIR SUDDEN DEMISE AND EXAMINES THE SUCCESSES AND FAILURES OF ONE OF THE MOST PROMINENT BANDS OF THE DECADE

INFATUATION is the true pop response, not considered and evaluative: we all see that, even celebrate it. Why then do we have such trouble with what follows on from infatuation — partisanship, irrational, abiding faith? I'll come clean: for me, The Smiths can do no wrong. Donning my critic's cap, I can see they have regularly produced weak work. But this is what a love affair is like—a long waiting out for a repeat of that initial, initiating rapture. And The Smiths have regularly delivered that hit, restored to me that first rush.

For all the attempts of critics (especially on this paper) to acknowiedge and celebrate the erotic relationship between star and consumer, fanaticism, the uncritical, is the one thing rock criticism can't cope with. But maybe the letters page sluggards we regularly castigate for their disproportionate loyalty, to New Order or whoever, maybe they're closer to the truth of pop than we'll ever be.

Anyway, on with the "serious" business, the "responsible" criticism. Just remember that behind and beyond the lattice of argument, course the juices of adoration: pop's primal gush.

Why were The Smiths important"? Because of their misery. Never forget it. Around "Meat Is Murder" the critics suddenly discovered Morrissey's humour— George Formby was trundled out as a reference point. If you ask me, The Smiths could have afforded to be more humourless. The Smiths' finest moments— "Hand In Glove", "How Soon Is Now?", "Still Ill", "I Know It's Over" — were moments of reproachful, avenging misery, naked desperation, unbearable reverence—free of the "saving grace" of quips and camp self-consciousness. If there was laughter it was black, scornful, scathing. If The Smiths had only produced sunny, cuddly stuff like "Heaven Knows", "Ask", "Boy Witn A Thorn", they would have merely presaged the perky negligibility of The Housemartins, the sound that grins itself to death. The Smiths were heroic party-poopers at the "Top Of The Pops" office do, glowering at the forced jollity; they were like those gauche youths who turn up to house parties only to cling to the dark corners in chaste disdain, driven by the naive, vaguely inhuman conviction that all merriment is a lie.

The extent to which they were funny actually diminished their impact: it made Morrissey loveable, but it made the music easier to live with, deprived it of edge. Compare The Smiths with Throwing Muses. Both Morrissey and Kristin Hersh work with and within the flux of adolescence—the vacillation between agoraphobia and claustrophobia, possibility and constraint; the feeling that one's body, and the cultural meanings attributed to it, are a cage.

Morrissey crystallises that flux, turns it into couplets, quips, aphorisms, insights, a wisdom we can draw comfort from. Hersh reproduces that flux, her voice is flux. The Smiths are a synopsis of pain, a resolution — awkwardness and alienation ennobled, given poise. Hersh is the presence of pain, of falling apart; her voice, the intolerable stress it inflicts on the words, is the sound of the inconsolable wrestling with the insoluble. The difference is between commentary and embodying, identification and voyeurism. It's the reason why The Smiths are more powerful as a pop institution, and why Throwing Muses are more powerful as art.

And The Smiths were important because of their extremism, their unbalanced view of the world, their partiality. Morrissey is a character in a pop era of nonentities, and characters are always lopsided, contrary, incomplete, the sum of wounds and bigotries. There's no such thing as a full-founded character. Morrissey is "half a person", his very being constituted around lack, maladjustment—this is the vantage point from which he launches his impossible demands on life, his denial of the reality principle. Satisfaction and adjustment could never enter The Smiths' picture, for this would breach their identity.

This is why Morrissey can't "develop" as an artist. How can he grow when his very being is constructed around the petulant refusal — "I won't grow up"? The refusal to be responsible and motivated, to get a job, to take on the brutalisation and disenchantment entailed in "gainful" employment. The refusal to collude in the state of dreamlessness that is adulthood, even to the pyrrhic point of clinging stubbornly to the state of being unsatisfied, forever. Having perfected this petulant stance, all he can do is reiterate it—with a self-deprecating acknowledgement of the onset of self-parody, "Stop Me If You Think You've Heard This One Before".

Not that Morrissey's misery is something we simply identify with. What The Smiths were about was narcissism, damaged, exploding back with a defiant fantasy of martyrdom. The Smiths seduce us into aspiring to the same heroic pitch of failure and exile. The tragedy of The Smiths is that Morrissey can only become the victim of the perfection of his style. Like Jagger, like Rotten he is condemned to live out its pantomime forever.

WHEN The Smiths first appeared they seemed to be a reaction against the opulence/corpulence of nouveau riche New Pop. Really, they were a return to a different vision of "new pop", the Postcard ideal. The Smiths were the second coming of Postcard — the whiter-than-white "pure pop"; the sexual ambiguity; the Luddite insistence on guitars; Edwyn Collins' avowed rating of romance over sex; the swoon instead of the earthy R&B rasp; the flustered undanceability.

What The Smiths returned to the charts was something that pop had seemingly left behind — adolescence. New Pop had rapidly lost its mischief and settled down into a kind post-rock, post-teenage maturity, peddling naff fantasies of sophistication to a new generation of monied teenyboppers whose only desire was to grow up as soon as possible. The Smiths, on the other hand, peddled fantasies of innocence to those in the process of leaving behind their adolescence. Their constituency was the silent majority of music paper readers that critics love to sneer at; students, ex-students, and those destined to be students (sixth formers and fifth formers).

Situated in the space between the constraints of childhood and of having a career, these are people who dream for a while of wanting a vague something more from life, yet are saddened oy these dreams because they know deep down they'll probably relinquish them, buckle down to a lire of mediocrity. When this happens, the records get harder to listen to, the music gets to be like a reproach, stirring up the taunting ghosts of prematurely foregone dreams. Nagging "but... you've got everything now", "please save your life / because you've only got one"... which is why people give up pop music, in the end.

New Pop, far from being a bright new beginning, turned out to be merely the inauguration of global designer-soul, the soundtrack to the new yuppie culture of health and efficiency. In the face of the benign totalitarianism of leisure capitalism and its off-the-peg self-improvement, The Smiths glamorised debility and illness, advocated absenteeism, withdrawal, the failure to meet quotas of enjoyment. The profound embarrassment of Morrissey's dancing turned the lack of oneness with your body into glamour. All the self-squandering and deficiency of lifeskills that animated The Birthday Party and The Fall, The Smiths turned into brilliant, glamorous, consumable pop, two minute bursts of otherness in the heart of the charts.

They were meant to be The Rolling Stones of their time. If the Stones camp appropriation of black R&B animalism was the supremely relevant response to straitlaced, petit bourgeois English suburbia, then The Smiths camp refusal of the travesty of healthy sexuality that black pop degenerated into, was the appropriate response to Eighties "liberated" suburbia. Tne Smiths deployed the imagery of provincial northern life, the residues of a lost Englishness, as a weapon against the cheap hedonism of an Americanised southern England. The very parochial stuffiness that the Stones reacted against had somehow become an alluring and reproachful memory.

For the Stones, desire was obviously the enemy of materialism, work and a planned life. But today desire has become incorporated into the domain of your life's work. Getting in touch with your body, getting in touch with your soul, has become a humanist work-out. "Satisfaction" had become feasible, something you could plan for. The Smiths, hooked on the glamour of the misfit, could only occupy an IMPOSSIBLE position, attempt to create a rock music where aggression was replaced by vulnerability, hedonism by ascetism.

From the private pain, the furtive minor language of unrequited obsession, that they began with, Tne Smiths went public, became the rock band, the pollwinners, ombudsmen for wider grievance. Whether speaking out as for the silent rock majority against the soulboy mediacrats, or representing The Smiths as media martyrs, victims of criminal under-representation, Morrissey has ascended a paranoiac spiral of statesmanship (paranoia is only inverted narcissism) — check the progression from "Panic" through "The World Won't Listen" and "Louder Than Bombs", to "Strangeways, Here We Come".

MORRISSEY is a new kind of pop star. Steeped in the history of pop, in writing about pop, himselr a fanatic, he has an acute understanding of the mechanics of fan obsession. And like various other bright fellows he wants to use the mechanism of idolatry to introduce some kind of intelligence and difference into pop.

Unlike most of these bright chappies, Morrissey is a natural. He has it. And this is when the most interesting pop occurs — when the enigmatic, illegible, wholly arbitrary forces of fascination (with a singer's face, body, voice) coincide with meaning. Not that Morrissey realises this. His own version of The Smiths' importance is incorrigibly trad-rock — hailing them as the sole vanguard of Meaning and Humanity in the Age Of Formica. He'll dismiss Prince because "he imparts nothing", not realising that both he and Prince "say" more in a single trail of falsetto than in their entire lyric sheet; that their difference, their resistance is embedded in their very mode of utterance. But that's The Smiths for you — a weird mix of the reactionary and the progressive, Luddite rockism and polymorphous androgyny. Perhaps the appropriate contradictory response to schizophrenic times, where we're leaving a repressive past for an unknown, unstable future.

Who wants to grow up? Who wants to go back?

Comments

Post a Comment