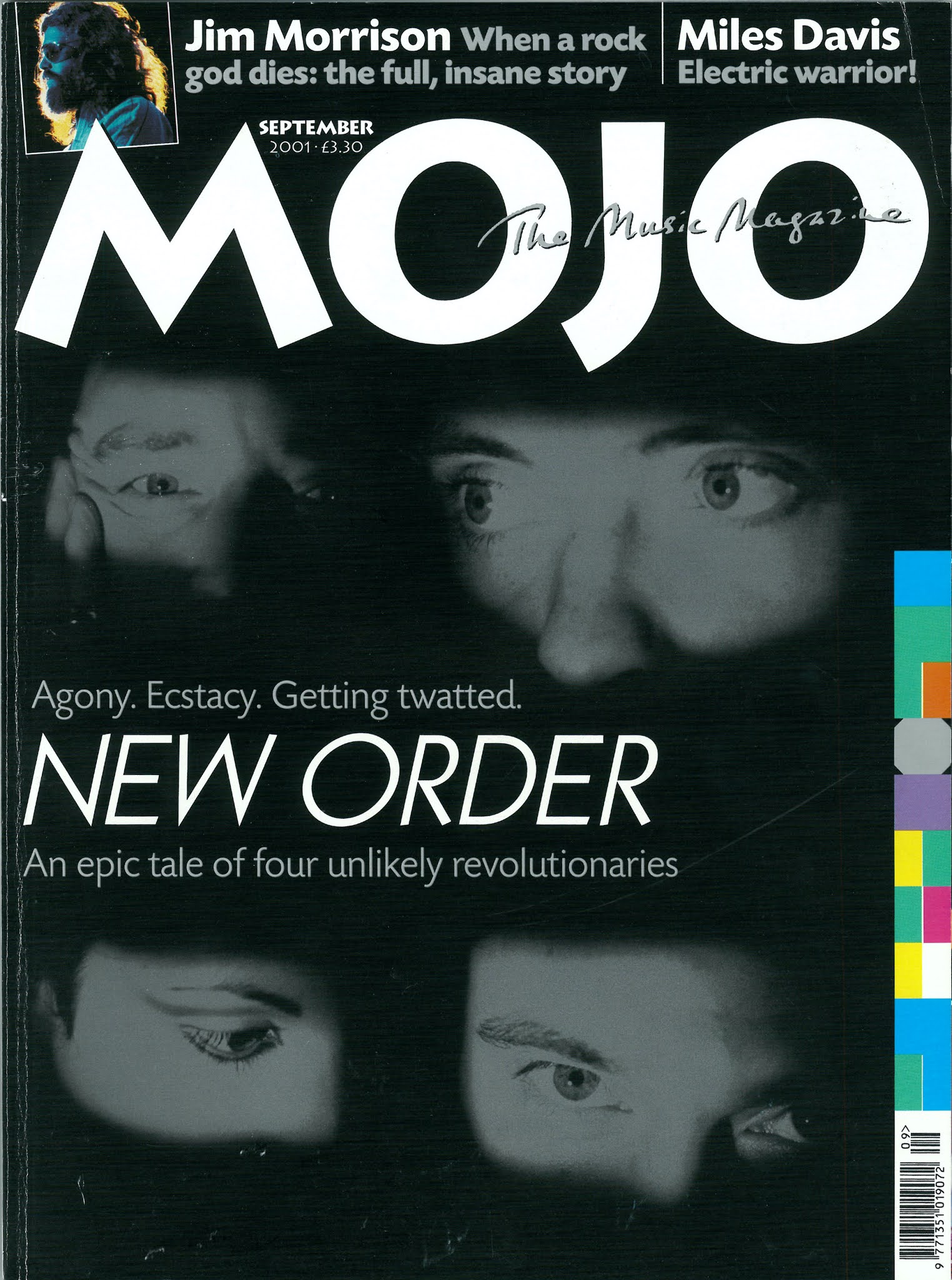

2001 09 New Order, Mojo

VORSPRUNG DURCH TECHNIK

For Joy Division's three surviving members, the suicide of Ian Curtis should have marked the end. Then came a new dawn of technology, Ecstasy and redemption. The incredible fall and heroic rise of New Order, by Roy Wilkinson.

High in the rolling Cheshire greenery, a familiar bass line sounds out. The location is a farm-cum-studio just outside Macclesfield - a sturdy, stone-built construction sitting close to both the village of Pott Shrigley and Tegg’s Nose Country Park. To admirers of contemporary popular music, the title of the song that’s echoing out over the hillside is even as distinguished as such piquant north-country place names, “love,” goes the song, “love will tear us apart again.”

There are further unmistakable clues to today's music-makers. In the driveway sits a Mitsubishi Shogun 4X4 jeep. The number plate features bold, personalised lettering: H100 KYS. And, as the bass player’s brazenly self-referential registration glints in the morning sun, here comes the drummer and co-owner of this property. We are, in fact, at the home of' New Order drummer Stephen Morris and keyboardist / guitarist Gillian Gilbert. New Order are rehearsing for live dates, their first since playing London’s Alexandra Palace on New Year’s Eve 1998.

Over on the neighbouring hilltop shines White Nancy, a 19th century folly that, every Christmas, local merrymakers re-paint as Father Christmas or a plum pudding. Stephen and Gillian's farm is the place where New Order first assembled, back in the autumn of 1999, to begin collective work on what would become their seventh studio album, Get Ready. But the farm also holds other surprising and fascinating dimensions.

Stephen beckons us into a barn. Peter Hook has his bespoke number plates, but it seems his rhythm section partner easily outdoes him for automotive intrigue. Inside this ramshackle outbuilding sit the hulking, green forms of four tanks.

On the far side of the barn sits a Ferret armoured car, a dashing post-war development of the earlier Daimler Dingo. Nearby is parked a Samson, a bijou representative of the Scorpion family of ‘light’ tanks.

“That one has a nice little trick," says Steve. “If you jam on one brake, it just spins in a circle. Excellent doughnuts.”

Most ominous of the four metal juggernauts is an FV 433 Abbot self-propelled gun, complete with huge, looming cannon. Then, completing the quartet is an FV434. the RAC van of the tank world, a recovery vehicle.

“It’s pretty vital, this one," informs Steve. “You need it to get the engine out of the Abbot. Can you take them on the road? ’Yeah, course you can. In fact, you don’t even need an MOT. You just stick on some L-platcs and you’re away"

Astonishing stuff. However, the impudent soul might suggest that Steve has made a fundamental error with his particular choice of battlefield runarounds. Given Steve’s musical heritage, given the fact he once played drums for Joy Division - a band who would occasionally stick pictures of the Hitler Youth on their single sleeves — shouldn't Stev e have gone lor a nice Panzer Mk IV or Tiger tank?

“Nah,” he grins. “They’re very rare, I couldn’t afford them."

Perhaps even more remarkable than Steve’s barn full of tanks is the fact that New Order are here at all. Today, this group glow with artistic contentment, but if you cut back eight years to the last New Order album, the picture was very different. The making of 1993’s Republic was a black and blighted period. While that album was being recorded, both the band’s then label, Factory Records, and a nightclub called the Hacienda entered terminal financial meltdown. There was also the breakdown in the band’s personal relationships, and a lot of cocaine. At this time, bags of money were being rushed around the country in desperate, finger-in-the dyke attempts to keep the Hacienda open and feed New Order's recording costs.

Republic was recorded at Real World, Peter Gabriel’s studio, near Bath. One New Order associate recalls a drive he made down from Manchester to see how the record was going. He was, he says, also asked to deliver some cocaine. As he pulled into the studio’s driveway he found a member of New Order, apparently, waiting for him. “Christ,” our emergency drug mule thought. “How long has he been standing there?"

“Yeah...” Peter Hook sighs wearily, taking a break from today’s rehearsal. “I suppose there was quite a bit of that [cocaine] around. Those were awful times — you needed something to hide the pain. We were having meetings every day about how Factory was going bankrupt. It wasn’t the greatest atmosphere in which to try and create joyous music. Pottsy [David Potts, Hook’s partner in his other band, Monaco] used to say to me after Republic, ‘You’ll do another album.’ I just said, There is no way on fucking earth that we will do another album. Not a fucking chance...”

Gillian: "We were left in the dark and treated like a hamster on a wheel. It was all, ’Get the LP done! Get the LP done!’ We knew something fishy was going on but we were told nothing. There were interminable bloody meetings — arguing about getting the bloody settee recovered in Dry [Factory’s Manchester bar].”

“Our business affairs were a mess,” says New Order’s singer and guitarist Bernard Sumner. “Factory was going under and the Hacienda became a black hole for all the cash we’d been earning on tour. The studio hills were going unpaid and we weren’t getting on as individuals. I was off working by myself in the studio — just me and [producer and co-writer] Stephen Hague - and going a bit mad. The rest of the kind thought I’d turned into this megalomaniac. 1 wanted them to come and help me out, but they thought I just didn’t want them there. It was horrible.”

As rehearsals move on at the farm, a distinctive keyboard line sounds across the patio. However, this melody isn’t being played by New Order’s keyboard player. Having contributed to Get Ready, Gillian Gilbert will not he taking part in New Order's forthcoming schedule — neither playing live nor involved in any promotional or press activity. Instead, she’s taking time out to look after her and Stephen’s youngest daughter, who is recovering from serious illness. Today, the keyboards arc being played by Gillian’s replacement Phil Cunningham, formerly of Macclesfield band Marion. But, as one figure from the New Order story moves out of the immediate picture, other links with the past will he maintained via New Order’s imminent live shows. The keyboard line that Phil is practising and perfecting is the haunting motif from Joy Division’s Isolation.

TWO MONTHS PRIOR TO MEETING New Order at Gillian and Stephen’s farm, MOJO takes a place at the baronial supper table at Hook End Studios in Berkshire. Former owners of this studio have included David Gilmour and Alvin Lee (the studio currently belongs to Trevor Horn and his wife and partner Jill Sinclair). Tonight, however, sees its own pan-generational rock moot. Hooky (as everyone bar his three children knows the New Order bassist) and Bernard are at the head of the table, tucking into their beefy tranches. Bobby Gillespie and Andrew Innes are both enjoying the vegetarian option. Also in attendance is Alan Wise, long-term New Order acquaintance and former manager of Nico (anyone who has read James Young’s Nico-themed memoir Songs They Never Play On The Radio will know Alan as that book's shaky, silver-tongued voluptuary Dr Demetrius).

One character notably absent, however, is Rob Grctton, long-time manager of both Joy Division and New Order. Rob died from a heart attack in 1999, meaning that Get Ready is the first New Order album created without his input. According to Tony Wilson, it’s taken three people to replace Gretton. New Order are now managed by former Gretton assistant Rebecca Boulton, former New Order tour manager Andy Robinson and, for America, Tom Atencio. And, as with Republic, the new album has been A&R’d by Pete Tong.

Just before dinner, the Primal Scream duo completed their contribution to a track for New Order’s new album. The track is called Rock The Shack and bears close kinship to Shoot Speed, Kill Light, the song that Bernard Sumner played guitar for on last year’s Primal Scream album, XTRMNTR.

After Bernard has discussed the sexual proclivities of the studio dogs (“They’re all related — the father and son dogs take turns shagging each other up the arse”), table talk turns to the particular advantages of Harry Ramsden’s 32-ounce cod special (“It’s brilliant,” proclaims Hooky. “If you finish it, you get a certificate"). Then matters alight on the previous evening’s post-recording booze-up. "One thing led to another,” says Bernard. "The last thing I remember is Bobby walking around with a bottle of white wine in one hand and a bottle of red in the other.”

Bobby Gillespie is a particularly illuminating fellow traveller. In the early ’80s, before he drummed for an early version of The Jesus And Mary Chain, Gillespie played bass in a New Order inspired band called The Wake. The Wake's very name summons a deeply different time in New Order’s history. New Order played their first British concert on July 29, 1980 at a small Manchester club called The Beach. It was around 10 weeks after lan Curtis, Joy Division's frontman, had hanged himself.

Curtis’s increasingly severe epilepsy and the meditation he was taking for it have been posited as one factor behind his suicide. There was also his complicated private live, with the singer involved in an uneven love triangle with his wife Deborah and his Belgian mistress Annik Honorc.

“Ian wasn’t a depressed person,” says Bernard today; now sitting in a lay-by in his Mercedes jeep for the formal MOJO interview. “He wasn’t a depressed person or a heavy person until he got ill and his life got into a mess. The tablets he was on for epilepsy really affected his mood. Then he got depressed. Before that he was just like the rest of us.”

Clearly, this loss of a young life had a profound effect on those around lan. But it’s a measure of New Order’s honesty and unaffectedness that they can admit that their grief also shaded into worries about themselves.

“We were very distraught about what had happened to Ian," says Bernard. “He was a great friend of ours. But, on a professional level, we’d lost our singer. It came at that time when you were just moving from the end of adolescence to becoming a young man. At that time you’re questioning your place in the world. We thought we’d found it - we'd found our holy grail. Then Ian died and it was like, Oh... There was nothing left... But we’d burnt our bridges, we had to carry on.”

With the remaining three-quarters of Joy Division determined to keep on making music, it did cross their mind to seek a singer outside the band.

“We did think about getting in a singer,” says Bernard. “I remember this guy coming up to me in St Ann’s Square in Manchester and saying how he was sorry about Ian’s death, but that he’d like to be considered. He gave me his number, but I couldn't call him, because he was into Steely Dan! The hurdle of replacing Ian with someone from outside was just one we couldn’t cross. It sounds awful, but it was like your pet dog dying. You can’t just go out and buy another one - it doesn’t work like that.”

Joy Division’s legacy was clearly going to be difficult to transcend. The band are now commonly acknowledged as one of the most singular, most astonishing rock bands ever - a band who with just two studio albums, Unknown Pleasures and Closer, created something strange, bewitching and enduring.

As Peter Saville, Joy Division and New Order sleeve designer, has observed: “Manchester is a city of concrete underpasses and a gothic-revival cathedral. For me, Unknown Pleasures was the concrete underpass, while Closer was the gothic cathedral.”

Here was rock music that was both ancient and modern. It’s a music that thrums with such a preternatural authority that it doesn’t seem daft to set it beside the most haunted, driven blues. But it’s also music that hisses and clanks, flourishing the die-cut clean edges of the industrial age. Producer Martin Hannett decked Unknown Pleasures in stark, reverberating incidental noise: smashing glass, wooshes of electronically generated sound. These were, clearly, hints at the connections in his own mind between rock's metronomic heartbeat and the harsh report of factory production - Hannett talked of once visiting an industrial unit and being struck by the echo between rock’n’roll and the rolling mill. After Unknown Pleasures, Joy Division began to experiment with the electronic instrumentation that was to become such a part of New Order.

As Joy Division prepared to enter Islington’s Britannia Row Studios in March 1980 to record Closer, they d already acquired two synthesizers, an ARP Omni and a home-made device which basked gloriously under the name of the Transcendent 2000.

“In Joy Division I was primed for technology,” recalls Bernard. “I used to build synthesizers out of kits that you got out of the back of electronics magazines. We had this boffin guy, Martin Usher, who worked with us. He had this Hell’s Angel as a lodger. So Martin used to design circuits which I would go away and build and we’d pay him in tabs of LSD. He would pass these on to this Hell’s Angel, who had an enormous appetite for taking acid.”

Jov Division’s new synth arsenal could be heard on Closer's Decades and Isolation. But other songs from this period contained the sound of rather less sophisticated machines.

"Atmosphere [released March 1980] was written on a Woolworths organ,” says Bernard, ‘it had chord buttons, which was useful, because I couldn’t play chords on a keyboard. It also had a little fan to keep it cool. I used it live, until a roadie dropped it.”

While Bernard was bravely improvising with the Woolworths wall of sound, Ian Curtis was also finding some recherche inspiration. The song Atrocity Exhibition took its title from J.G. Ballard’s avant-garde book about Nissen huts, B-29 Superfortresses and an "electroencephalogram of Albert Einstein”. Perhaps it was for the best that the rest of Joy Division were utterly unaware of such lyrical impulses.

“No, I didn't have a clue where that title came from,” says Bernard. “People might think this is weird, but we never listened to Ian’s lyrics until after he died. We never really asked him about his lyrics. The only two songs I ever asked him about were She’s Lost Control and The Eternal. She’s Lost Control is about an epileptic girl who Ian met while he was working at a rehabilitation centre — she later died during a fit. The Eternal is about a boy with Down’s Syndrome who lived near Curtis when he was growing up in Macclesfield. In New Order, the rest of the band don't ask me about my lyrics and I'm glad they don’t.”

These days Joy Division’s influence is manifest. They are seen as the motherlode by untold young bands (Placebo, JJ72,. Mogwai, Doves). They’ve been covered by anyone from Paul Young and P.J. Proby to Nine Inch Nails anil Grace Jones, while George Michael, strangely enough, lists Closer as his favourite ever album. Both The Smashing Pumpkins and Red Hot Chili Peppers have played entire sets of Joy Division covers, solely for their own gratification.

When, in turn, Joy Division’s influences have been dissected, a familiar list has been uncovered: Iggy Pop, Kraftwerk, the Sex Pistols, The Velvet Underground. But it seems there’s also a whole other range of music echoing through Joy Division — groups and musicians some way removed from the punk-compatible brew that the band are normally linked with. Take, for example, Wishbone Ash.

“I was definitely a rock fan when Joy Division formed,” says Hooky. “Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin, Wishbone Ash, Black Sabbath, The Groundhogs. I was a big fan of The Groundhogs - fantastic band. Then everyone started saying how Joy Division sounded like The Doors but Bernard and I had never heard The Doors, never. Ian played us a Doors LP and, fuck me, we did sound like The Doors. After that we sometimes did Riders On The Storm, but no one seemed to notice. They just thought it was us, as usual, sounding like The Doors! We played it a few times, probably just before Unknown Pleasures came out.”

Barney, while thrilling to Iggy’s Lust For Life and starting to experiment with the circuitry that would become a crucial part of New Order, was also taking in other, more traditional sounds.

“I started listening to Neil Young when I was in Joy Division,” he says. "At that time I was really into guitars. I liked Led Zeppelin because of the guitars and T.Rex and Ennio Morricone’s spaghetti western music because of the guitars. What I like about Neil Young is that he does a lot with a little. He made me realise that you can play solos on one string. Neil Young’s got this thin, reedy voice and I suppose in some ways it's not quite right, but it just sounds beautiful. In Joy Division we used to play Lust For Life and try and copy riffs of it. But we also listened to Love - we tried to do a cover of their 7 And 7 Is, but we only got about a verse into it before it got a bit tricky and we gave up.”

Of all the members of Joy Division, it’s perhaps Stephen Morris who had the most surprising, quixotic listening habits. For one thing, he had a yearning for the West Coast sounds of Quicksilver Messenger Service.

"Yes, that would be my juvenile acid period,” he says. “I was into a lot of West Coast stuff back then, as well as Hawkwind and Can and Amon Duul II. The other thing that I used to listen to a lot was Captain Beefheart. Recently, when I had chicken pox, I went back to all this old Captain Beefheart and I could hear things in it that I never realised before—all the drumming was really complicated and dense. 1 think my own drumming must have definitely been influenced by Captain Beefheart, even if it came through subliminally. I actually went to see him live around the time of Clear Spot - I’ve still got the reviews and cuttings stuck inside my copy of the album.”

It seems the teenage Stephen’s predilection for LSD had other consequences than enhanced enjoyment of, say, Hawkwind’s The Psychedelic Warlords (Disappear In Smoke).

“Actually,” he says, 'I got kicked out of school for taking acid. I had this friend who thought he had such cool, tuned-in parents that it would be nice to tell them he’d just had an acid trip. So he did and they went straight down to the school. I bloody well got it off him, but I seemed to get identified as the bad influence. Happy days, though. We used to go and sit in a field with a cassette player as it was going dark and play Tago Mago by Can till the batteries ran out. I've heard people say that Hooky’s style of lead bass playing was influenced by Can. It's not the case, though. He just played like that because it was the only way he could hear himself in rehearsals.”

The observant visitor of Gillian and Stephen’s farm might note that Stephen's interest in the world of tanks stretches further than the vehicles in the barn. High up in a window sits a 1/35th scale model kit of a World War II German Tiger tank. Back in the early ’80s, the presence of such an item would certainly have been seized on as conclusive proof of New Order’s ‘Nazi’ affiliations.

At this time, Private Eve would run ostensibly serious exposes of New Order and Factory Records’ supposed Fascist leanings Of course, Joy Division and New Order had provided some fuel for such accusations.

Joy Division took their name from a book called House Of Dolls, which is partially set in a World War II concentration camp. In the context of Joy Division, this book has generally been depicted as a sado-masochistic novel. However, the actuality is stranger. The University of Florida’s Judaic Studies Programme has detailed how the book was originally written in Hebrew and “based on a diary kept by a young Jewish girl subjected to enforced prostitution in a concentration camp. Danielle Preleshnik, the protagonist, was in reality [the author] Ka-Tzetnik’s sister.”

New Order derived their name from a newspaper headline about “the New Order of Kampuchean Liberation”, unaware that Hitler was also keen on the phrase. Then there was Joy Division’s first release, their self-financed Ideal For Living EP. On the front cover was an illustration of a drum-beating member of the Hitler Youth. Inside was a reproduction of a photograph from the Warsaw ghetto - a Polish boy cowering before a German soldier.

Bernard now winces at the memory of such loaded imagery. But, as was pretty evident even at the time, the band were hardly trying to glorify the Third Reich.

“What we were trying to get across,” says Bernard, “was how powerful this Nazi imagery was. I was working in graphic design at the time and I was fascinated by the way imagery could be used to manipulate a great number of people. And the inside sleeve was showing what that imagery led to. But I do have big regrets about trying to use that imagery in that way. It was naive. It was stupid.

"I can’t remember,” says Stephen, “if we started off laughing at it [the ‘Nazi' accusations] and then got annoyed, or if we started off annoyed and ended up laughing at it. As far as the Second World War goes, I was only interested in the Airfix aspect.”

“I am fascinated by that period," continues Bernard. “But I’m not a Nazi. I grew up in my grandfather's house and it was full of wartime memorabilia —gas masks, tin helmets. At the end of our street there was a couple of houses missing, where they’d been bombed during the war. That does have an affect on you when you’re a young kid. Everyone's so horrified by what the Nazis did that we’re constantly still searching for an explanation. We want to know how someone could do that but the explanation never really comes, no matter how many documentaries we see or books we read.”

While Joy Division were deploying their controversial ideas, they were also sporting a distinctively austere look, one cultivated by shopping for trousers at the Army & Navy and, as Stephen Morris recalls, receiving “prison camp" haircuts from Rob Gretton.

“That was when we were trying for the submarine commander’s look,” remembers Hookv. “It was our military period. You think back and realise you were just 20. It was just daft, it was fantastic... What better way to be daft than to join a group'’”

For a period, Bernard even adopted the Germanic surname of Albrecht. This was taken from the manufacturer's name on a piece of equipment at Cosgrove Hall, the graphics and film company where he worked. At the time, the company was developing some notably heroic film projects. Mercifully, these didn’t include a new colour tint of Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph Of The Will. The company was to become renowned for its work on DangerMouse.

"IF YOU GO OUTSIDE," ADVISES BERNARD, “YOU CAN see Hooky’s head bobbing up and down. He looks like he’s having sex with a public schoolboy.”

Six weeks before the session with Primal Scream at Hook End, MOJO is in attendance as New Order record at Real World, a rather lowly collection of stone buildings, complete with wandering ducks, open fires and splendid table tennis facilities. But right now, Bernard is indicating the scope of New Order’s current fitness regime. He has just returned from a run. Hooky is upstairs on his rowing machine, evoking, for Bernard at least, images of energetic congress in the dorm.

Running and rowing completed, the band adjourn for dinner.

Tonight, table talk takes in the odd comedic suggestion for the album title. “It’s going to be called Fear Of A Hangover," says Bernard (other titles later be considered and discarded include Seven and Organisation). Chat also turns to 24 Hour Party People, the forthcoming film about Manchester music, Factory and Tony Wilson.

“Who’s playing Shaun Ryder?” ponders Bernard. “Is it him out of The Pogues?”

“Nah," rejoins Hooky. "I heard that they'd spent half the budget on all the make-up they needed to make a normal human being look like Shaun."

Hooky, Bernard, producer Steve Osborne and several assistants then begin work on a track provisionally titled Freefall. The song will eventually appear on Get Ready as Someone Like You. These days, Bernard’s position as New Order singer is evidently secure. However, following Ian Curtis's death, as the nascent New Order sought a singer Stephen Morris was initially thought to have the best voice of the remaining members of Joy Division. However, he soon withdrew from the New Order vocal handicap stakes.

“The idea of a singing drummer wasn’t a great one,” says Stephen. "Look at the previous examples - Phil Collins, Paper Lace, The Eagles. finding who should sing was all about natural selection; it was a Darwinesque process and it soon became clear that the singing drummer was going the way of the dodo.”

According to Tony Wilson, manager Rob Gretton was particularly adamant that the band shouldn’t go "outside the family” for a singer. New Order played a few American dates as a trio, with each band member singing a selection of tracks. They also tried recording the song Ceremony in New York. Ceremony was to become New Order’s first single, but the single version was recorded in Stockport’s Strawberry Studios, now home to an office supplies company. By the time Ceremony was recorded, Gillian Gilbert had joined New Order. She was friend of Stephen Morris’s younger sister who had known the band for years. Indeed, she had once appeared on-stage with Joy Division - at Liverpool venue Eric’s after Bernard had injured a hand during some backstage buffoonery.

Ceremony, together with B-side In A Lonely Place, were inherited from Joy Division, both written in the week before Ian Curtis died. This must have made strange listening for one party in particular - Ian Curtis's widow; Deborah.

“Actually," she says today from her home, "1 thought that was a nice way to tie things up. But I didn’t want anyone to carry on after that. I just wanted everything to stop. But I'm now glad that New Order exist. I only began to enjoy New Order’s music when the True Faith single came out [in 1987]. My son was quite young at the time and he loved the video. So it was through him that I began to appreciate New Order.”

Now there’s the possibility of further connection between Deborah and New Order. Her book about Ian Curtis and Joy Division, Touching From A Distance, is currently being turned into a movie script. Deborah hopes that New Order will provide the score for the eventual film.

New Order’s next two releases saw the band attempting to establish their own agenda. September 1981’s Procession single contained a remarkable construction with B-side Everything’s Gone Green. But it was November ’81’s Movement album that gave the band the latitude to attempt a wholesale transformation. By consensus, it seems they weren’t ready to make this leap.

“Movement was a transition.” says Bernard. “It was a very uncomfortable period. To me, the only bad album we’ve made is Movement We were struggling to find a direction and at the time I was very depressed, so I associate that feeling with that album.”

Hooky also recalls Movement troubled genesis. It was the last album that the band were to make with Martin Hannett, the mercurial Manchester producer who had overseen both Joy Division albums.

“It was very difficult doing Movement " says Hooky. “Martin was at his really low point. He was off his head all the time. With Joy Division, the sound was always very complete, so it was easy for him. He just put his salt and pepper on, if you like. Then, with New Order, suddenly you had a bit of a wonky tyre, it needed pumping up, but Martin couldn't quite manage that. The way he used to try and describe what he was feeling was like, 'Uhhr, fuck, uhhr' (makes strange, ghostly strangulated noise). He was coming out with things like, ‘Make it more wooden, make it more helium-like.’ And we were just like, Aww, come on, just help us here... He always wanted to do vocal lines in a single, continuous take - he wouldn't patch things up. I remember Barney singing Cries And Whispers [an LP track released one month after Movement]45 fucking times. I don’t know how Barney fell, but I felt like fucking crying. But I like Movement. I like the songs on it and I like the fragility of the thing. It’s a moment in time.”

If Movement emerged as a thwarted thing, the group were far from at a dead end. They had a plan, one that was to increasingly immerse them in a world of binary codes, soldering irons, hexadecimals and electronic sequenced music.

“I read that Giorgio Moroder used a sequencer called a Roland MC4," recalls Bernard. “But that cost about £20,000 when we were on £50 a week."

In the ’70s, pioneering Italian producer Giorgio had teamed up with Pete Bellotte to produce two pieces of rapturous programmed disco for Donna Summer: the 17-minute Love To Love You Baby and I Feel Love.

As New Order’s own vision began to take form, Summer’s fecund pulses were key ingredients. At this point, New Order were surveying the globe for new inspiration. They were experiencing the electro sounds of New York clubs like the Paradise Garage themselves. Bernard was also receiving regular aural dispatches through his mail box: tapes of early "80s Kiss FM radio shows from New York, plus Italian disco records and a copy of Giorgio Moroder’s E=MC² album from a Manchester friend living in Germany.

New Order’s emerging genius lay in the way they fused the heart and the head, taking a world’s worth of lubricious dancefloor impulses and melding them with something more meditative, more melancholy. The ghost of Joy Division was to find its spectral presence splashed with joie de vivre.

Alongside New Order’s continued ability to expand the form of popular music, their other superhero-style special power was the strange, mocking, basilisk gaze with which they viewed music-industry conventions. Assisted by such remarkable minds as Rob Gretton, Peter Saville and Tony Wilson, they were able to look at the whole round of contracts, marketing and record-sleeve design with a gaze that was at once contemptuous and absurdist.

“I remember in the late ’80s," says Wilson, “New Order told me that, from now on, they were going to be deadly serious about everything. Then Barney turned round and said, ’Right, we’re gonna do a world tour - one night in Macclesfield and you can choose the other four dates.’”

The first record where New Order’s new musical formula emerged was barely noticed in its initial incarnation. Everything's Gone Green was first released before the Movement album, but was tucked away on the B-side of the Procession single. In December 1981, the song re-emerged in extended form, as the lead track on a Factory Benelux 12-inch single. A brilliantly astringent composite of clipped guitar and tinder-dry, subtly soulful sequencer, it unambiguously showcased the New Order masterplan. Behind the record lay pure, fingers-in-the-socket experimentation.

“Everything's Gone Green was the first time we used a triggered synthesizer,” says Barney “We triggered it by Steve playing a hi-hat beat into a 24-track tape machine and then sticking a wire into the tape machine’s VU meter and connecting that to the synthesizer Somehow it just worked. It was really was just about sticking a wire into something and seeing what happened."

But arguably, it was the next single, May 1982’s Temptation, where New Order truly found their voice. The sequencers were still there, the guitars were still there, but now there was something new - a sense of wide-eyed abandon, a sense of euphoria that immediately seemed a blue-skied expanse clear of Joy Division. It was the first record that New Order made under the influence of manifestly mind-altering drugs.

“I’d been turned onto LSD by a friend in Blackpool,” says Bernard. “I'd been up in Blackpool, and I was still kind of under the influence when I got down to the studio in London. In fact, for the next year or two we would always take a little bit of acid whenever we were recording. So I was tripping when I did the vocal for Temptation, and when I wrote the keyboard line. During the recording it started snowing and Rob and Hooky ran outside and got two massive snowballs. When I was recording the vocal they stuck them down the back of my shirt. If you listen to the 12-inch you can hear them coming into the studio and sticking it down my back.”

Maybe this chill down the back fired Bernard towards the startling array of whoops that he began adding to his vocal repertoire at this point. Whatever, Stephen also remembers the LSD-tickled session.

“Yeah, suddenly Temptation had that euphoric feel,” he says. “It had that quarter-of-a-tab feel. I think it was only Hooky who hadn’t taken a little bit of acid at that session. You couldn’t take a whole tab when recording a record, but a quarter seemed to help things on. Driving would have been out of the question, but you could still make a record and sometimes quite a good one.”

Of course, it was Blue Monday that, most of all, fixed New Order in the public mind. It reduced Neil Tennant to tears, so completely did it pre-empt the ideas he and Chris Lowe had been developing in private. It was a record that took inspiration from Donna Summer, Afrika Bambaataa ami Kraftwerk and, according to Barney, “totally ripped off the arrangement from a really rare Italian mix of Dirty lalk” by German dance act Klein & MRO.

"In London clubs,” recalls Bernard, "I started hearing this kind of dance music where people were trying to get these strict, machine-like beats with tape loops and live drums. They were doing music like Blue Monday, but with loops and real instruments. So I just thought, if we took our synthesizer we could use machines to make the things that these people are after. That was how Blue Monday came about. Wc were consciously making music that you could dance to, even though we weren’t going out dancing ourselves. When we were in Joy Division people didn’t go to clubs to dance, they went to headbutt people.”

Blue Monday’s legend is still undimmed among today’s clubland fraternity. As Pete Tong says, “New Order still have massive respect in the dance world. Blue Monday was made, what, almost 20 years ago. But the vast majority of DJs still know and revere this track.”

It’s also a record that engaged the minds of New Order’s original electronic influence - Kraftwerk, who had been part of things ever since Ian Curtis started using their records as Joy Division’s intro music. Now, the ever-inscrutable Dusseldorfers were repaying the compliment, making it their mission to discover exactly how Blue Monday was made.

“We heard later that Kraftwerk were totally fascinated bv Blue Monday,” recalls Hooky. “They heard it and thought (adopts the kind of strident German accent beloved of 'Allo Allo), Ve must go vere zey recorded ziz song Blue Monday.’

“So, they came over to Britannia Row and used our engineer. When they saw where we’d recorded the song they were taken back a bit. They were going, ‘Is ziz vot zey used to record Blue Monday? Ziz old desk and ziz old equipment?’ They couldn’t make it work it was all too old for them.”

BY 1989’S TECHNIQUE, NEW ORDER HAD BECOME A TRULY commercial force. The album, on which work started in lbiza the previous summer, would eclipse all their past successes, giving them their first Number 1 in Britain and reaching Number 32 in the US. The ascendancy had been achieved gradually, over the course of the three albums that preceded it - Power, Corruption And Lies, Low-life and Brotherhood - each refining further their electro-rock template. “I think the gradual growth was a conscious plan from Rob Gretton,” says Hooky. “He kept us grounded, by keeping us impoverished. I think he didn't want us to become isolated pop stars. It worked, because it gave us longevity.”

Technique was the album where New Order embraced a whole new generation of dancefloor mechanics: the acid house sounds they’d already heard in the Hacienda and the Ecstasy- fuelled atmosphere that was beginning to ignite the Balearic Islands. But, while New Order were burnishing their music with a whole new sheen, Peter Hook still apparently found time to push the faders for the mighty Sham 69.

“What happened,” explains Hooky, “was that Jimmy Pursey came down the studio to have a look around and mentioned that they were doing a gig that night. I said. Who’s doing your sound? No one was, so I immediately said, I'll fucking do it! So, it ended up with Sham 69 playing on a boat in the harbour and me and Andy [Robinson] fucked off our heads on the shore doing the sound by remote control. You had Borstal Breakout and Hurry Up Harry blaring out to all these ravers on the shore and nobody was even watching. Still, I loved it. Jimmy Pursey ended up asking me to produce the next Sham 69 album, but they got dropped by their record company.”

New Order’s attempts to record Technique in lbiza didn’t get very far. Instead they ended up negotiating days and nights lull of discos and crashed cars.

“We spent a lot of time in Ibiza getting off our faces,” says Bernard. “But we had come across Ecstasy before that - in America when it was still legal. We first came across it in Dallas. Then it was just like having a Red Bull or something.”

It seems the studio schedule in Ibiza soon began to wilt under the Iberian sun. New Order arrived with the majority of the basic tracks written, but the band were, initially, barely communicating and little was done. But emergency production assistance was on the way - in theory.

“The story from Tom Atencio,” says Stephen, “was that Brian Eno was meant to be coming out to work on the album, hut he never materialised. We heard that it was because he’d been told that we took too many drugs. I don’t know if that’s true, hut he never did show up.”

Some drum tracks were recorded and possibly a couple of guitar solos (band memories differ here), but work was soon abandoned for a wholesale round of hedonism.

“The studio had its own swimming pool and its own bar,” says Bernard. “The bar-tender used to put tabs of acid in his eyeballs and continue serving. We started out trying to do some recording. Steve doesn't really like the sunshine, so we’d be like, Steve if you want to record some drums, we’ll be by the pool if you need us. Then everyone just started going out and getting twatted. It was a bit hard writing lyrics when all the rest of the band and your girlfriend were all out at a club getting on one. So, I just thought, fuck this and started going out as well. We were all out dancing, definitely. Dancing every night... ”

Going out meant somebody had to drive. But it seemed no one was really in a condition to drive. As much as by the extended clubbing schedule, New Order’s Ibizan interlude is characterised by a string of smashed hire cars. The band can remember four, at least.

Happy Mondays’ dance totem Bez joined the Technique sessions and improved the car-crash tally by piling into a road sign as he attempted to read directions. Then there was Hooky and Andy’s attempt to find their way home after a night out.

“They'd met these Manc kids in a club,” recalls Bernard. “Andy's driving back and Hooky starts saying, ‘Something’s wrong here. I don’t know what it is, but something’s wrong.’ At that moment a taxi appears around a bend - at which point they realise they’re on the wrong side of the road. They smash straight into this taxi. The kids in the back aren’t wearing seatbelts and fly straight through the windscreen. Everything goes quiet. The kids are all hanging out by their legs... but all they do is let out this massive shout: ‘Yes! Yes! Front-end smash with New Order!’ Then the kids and Andy run off to hide behind the gravestones in this graveyard. Hooky’s there, trying to act normal with this copper, but these kids keeping shouting from behind the gravestones. Amazingly; the copper let Hooky oft.”

He shakes his head.

“So, all this was happening with us recording overseas. What does Tony Wilson then decide would be a good idea? Sending Happy Mondays out to record in Barbados. What was he thinking? It was almost as daft as deciding to do something like opening a nightclub.”

So, barely any work, but wild times were enjoyed. And the band embraced a whole new cultural milieu - even if the soundtrack wasn't to everyone's taste.

“I mean," says Hooky, “the music was terrible. It was all Thrashing Doves and Orange Juice and Paul Oakenfold shouting, ‘Aceeeid!’ But. there we were, out every night with the air-traffic controllers, all dancing, having a great time. We went to every single disco. It was ridiculous.”

The bulk of Technique was actually recorded at Real World, with New Order keeping their clubbing fascinations on the boil with weekly trips to London, to take in such pioneering acid house evenings as Spectrum.

“Recording in Ibiza did affect the mood of the album,” says Bernard. “Take a track like Fine Time - that was written over there the day after being out at a club."

Hooky concurs: “'That did become part of the album. We took on some of the mood of Ibiza, especially Bernard. It's still very much a rock album, but it has the upness, the specialness of all the things that we were in the middle of.”

Stephen sums up this particularly expensive summer holiday.

“The feel of Ibiza did definitely seep into the album. Apart from Fine Time, it is really a rock album. But it’s also got a kind of smile on its face - the kind of thing that comes with sunbathing at four in the morning before you go to bed."

These days Bernard Sumner's idea of relaxation is to drive north from his Cheshire home and take out the boat that he keeps on Ullswater on the eastern edge of the Lake District. The walls of his house are lined with art, including at least one original work by LS. Lowry (“Not the matchstick men," Bernard is keen to make clear. “I don't like the matchstick men. It’s a portrait I have.")

Peter Hook, meanwhile, takes such a rigorous interest in Joy Division’s history that it amounts to a kind of semi-official curatorship. Untold Joy Division photographs, live tapes and bootlegs occupy his house. Then there’s his special archive of long-abandoned Hooky stagewear.

“Yes,” he says. “I’ve got all the old leather trousers and me jackboots. You live the in the vain hope that you might be able to squeeze back into them one day:”

That day might yet arrive. He’s also been getting himself into shape.

“I've got this personal trainer and she fucking kills me," he says. “We’re all getting fit now for this tour. I go running three times a week and I don’t drink during the week. Mind you, when you do get twatted now you really pay. I went out last Sunday and I still felt terrible on Tuesday: It was the first time I’d been drunk in two months I used to be like that every day.”

Of the pop music of the moment, Bernard is keen on Daft Punk and Doves. Stephen gives the nod to Missy Elliott, while Hooky recently bought the new albums from the Stereo MC’s, Daft Punk and The Tom Tom Club. And, even as New Order were starting to record Crystal, the first single from Get Ready, Bernard felt compelled to make contact with current pop music’s more modernist wings. He compiled vocal snippets from the song and sent these to Germany, so that they could be used as samples by Hungarian DJ Corvin Dalek and his German counterpart Pascal F.E.O.S.

Bernard Sumner’s grandfather took part in the 1932 mass trespass on Derbyshire’s Kinder Scout, where honest, common folk affirmed the right to roam over nature’s goodness in defiance of landowner and lickspittle gamekeeper. His grandfather also knew Ewan MacColl, the Salford-born folk singer and lifelong member of the Communist Party. Such strands of socialist idealism are still discernible in New Order.

Stephen Morris can be roused to a completely atypical level of ire by mention of Tony Blair's Labour Party (“Spending all the fucking money on bloody posters”), while Bernard is similarly enraged by plans to extend Manchester Airport.

To this day. New Order remain a democracy, albeit a perverse and cussed one. Peter Savillc remembers one example of the New Order democracy in action. When once asked to decide on a new-look centre label for vinyl releases, they systematically, bloody-mindedly all chose a different colour. Rob Grctton was left with the casting vote. Perhaps inevitably, he selected yet another colour.

After the wracked, draining creation of Republic, New Order's idealism and intuitive sense of common mission evidently returned with the making of Get Ready.

“You’ve got to remember,” says Hooky, “me and Bernard have been together for 34 years [they met in the first year of secondary school]. Even so, I've enjoyed making this album more than any of them. We did get stuck in a rut with each other, definitely. We were so pissed off with the business side of it that we stopped caring about the people you should really be caring about - the ones who have given you everything, the other members of the group. Through all the years I’ve been in this band I never ever thought I’d ever sit down and tell someone 1 enjoyed making an album. I don't like making records, I’d much rather be playing live. I also get up at seven in the morning, so when all the other lot roll in at midday I’m bored shiteless. Me and Bernard worked it out. There are two types of people - the lark and the owl. He’s an owl and I’m a lark.”

It also seems that New Order’s tribal fealty stretches to another generation.

“Mv son's 11 now,” says Hooky. “Barney’s lad is 16. One of the proudest moments of my life in a group was when we played at Ninex in Manchester. Bernard's son and my son were both at the side of the stage.

They were looking at Bernard and they both knew the words better than him! I was really shocked, because I just didn’t think my son knew all the old songs. I was fucking amazed. Both me and Bernard had a tear in our eye there."

Former Smashing Pumpkins frontman Billy Corgan appears on Turn My Way. New Order also recorded a track with The Chemical Brothers, which wasn’t finished in time for inclusion on the album.

“I remember when we first met Billy,” says Hooky. “It was one of the first ever times that New Order played in Chicago. This American friend of ours asked if it was all right if he brought along his mate’s son because this guy was a big fan of Joy Division and he was thinking of starting a band. So there we were, out to dinner with a 15-year-old Billy Corgan. He didn’t say a word then, but I’ve met him loads of times since. You listen to a Smashing Pumpkins song like 1979 and it’s obvious he holds a real candle for Joy Division.”

Back at Gillian and Stephen's, the rehearsal moves through such undimming signature tunes as Temptation and Atmosphere, Blue Monday and Love Will Tear Us Apart, then onto 60 Miles An Hour and Close Range from the new album. It’s evident that Get Ready is no perfunctory exercise. It's an album that probably doesn’t have a song that will fly straight into the all-time New Order pantheon. But it's clearly an album of pedigree New Order, an album with gleaming consistency. In this respect, it probably most resembles Technique. And, like Technique, it’s a rock album.

“Yes,” says Stephen. “It’s a 4/4 fury, isn’t it? Actually, we did try one song in 5/4 time recently. We were asked to have a go at the theme for the Mission Impossible film, which is in 5/4 time. Yeah, it could have been us instead of Limp Bizkit. That’s a frightening thought, the kids would've been revolting. But, then again, they always are, aren't they?”

As New Order re-enter the fray, there are those who argue that they themselves still have a vital child-like aspect.

“The brilliant thing about New Order,” says Tony Wilson, “is that they are still open to it all. After all this time, after all these years, they are still children. It’s an odd thing. People ask me, are Joy Division and New Order different bands? The answer is no, they are utterly the same hand — the best band in the world.”

SIDEBAR

Heart and soul

Two years prior to his death on April 18, 1991, legendary Manchester producer Martin Hannett spoke at length to MOJO's Jon Savage. In this edited extract he discusses the Joy Division sound, Ian Curtis's suicide and Manchester opium culture.

How did you come across Joy Division?

"I went to see them supporting Slaughter And The Dogs ot Salford Tech. The PA broke down, and Steve and Hooky busked for about 15 minutes.

One of the things that drove me to drum machines was the appalling quality of drummers, but Steve was good, so immediately they had a red hot start. They were different from punk."

What was different about them?

"There was lots of space in their sound, before Bernard started falling asleep over polyphonic synthesizers. There used to be a lot of room in the music. They were a gift to a producer 'cos they didn't have a clue."

How did you see your job with Joy Division? Were you trying to make it dream-like, or simply more spacious?

"Just trying to make it appealing. The gig at Salford was very important. It was a big room, they were badly equipped, and they were still working into this space, making sure they got into the comers. The arrangements for recording were just reinforcing the basic ideas."

Were there a lot of drugs in Manchester in the late '70s?

"A lot? I don't think so, no. I didn't get into a lot of drugs situation until about '83."

When did you start doing smack?

"It must have been '78 or '79. Not a lot. Well. . I suppose it got to be a lot 'cos your tolerance builds up. Just enough. As Anthony Burgess says, they took away our opium and gave us beer and football. What a pity. You forget there was a big opium culture in Britain, especially in the North West. The climate predisposes everyone to chest complaints, and of course, number one dope for bronchitis is opium. It dries up the excess secretions.

I remember the night Joy Division played their last concert. We walked out of the gig, didn't know it was going to be the last. Why did Ian killed himself?

"It was an accident, wasn't it? Thirty two barbs and half a bottle of Scotch. I never saw the inquest. It did my head in. I was in the Townhouse with the Buzzcocks, and for some reason I wrapped the session up, rocketed back to the hotel, threw everything into the boot of my car, drove back to Manchester, got home by 10, was enjoying a coffee and got a phone call. That was the day after. Monday morning."

Was it totally unexpected?

"Yes and no. He'd tried to do it two weeks earlier, tried to kill himself, ended up in hospital and was released into the care of Tony [Wilson] and Lindsay [Reid], who dropped him off at his wife's house the day he died. He thought everything was a mess, and he wanted to organise himself before he went to the States."

The interesting thing about Ian was that onstage he was totally...

"Possessed. It was me who said 'touched by the hand of God' to a Dutch magazine. They like to remind me, you know, occasionally. He was one of those channels for the Gestalt: the only one I bumped into in that period. A lightning conductor."

Comments

Post a Comment