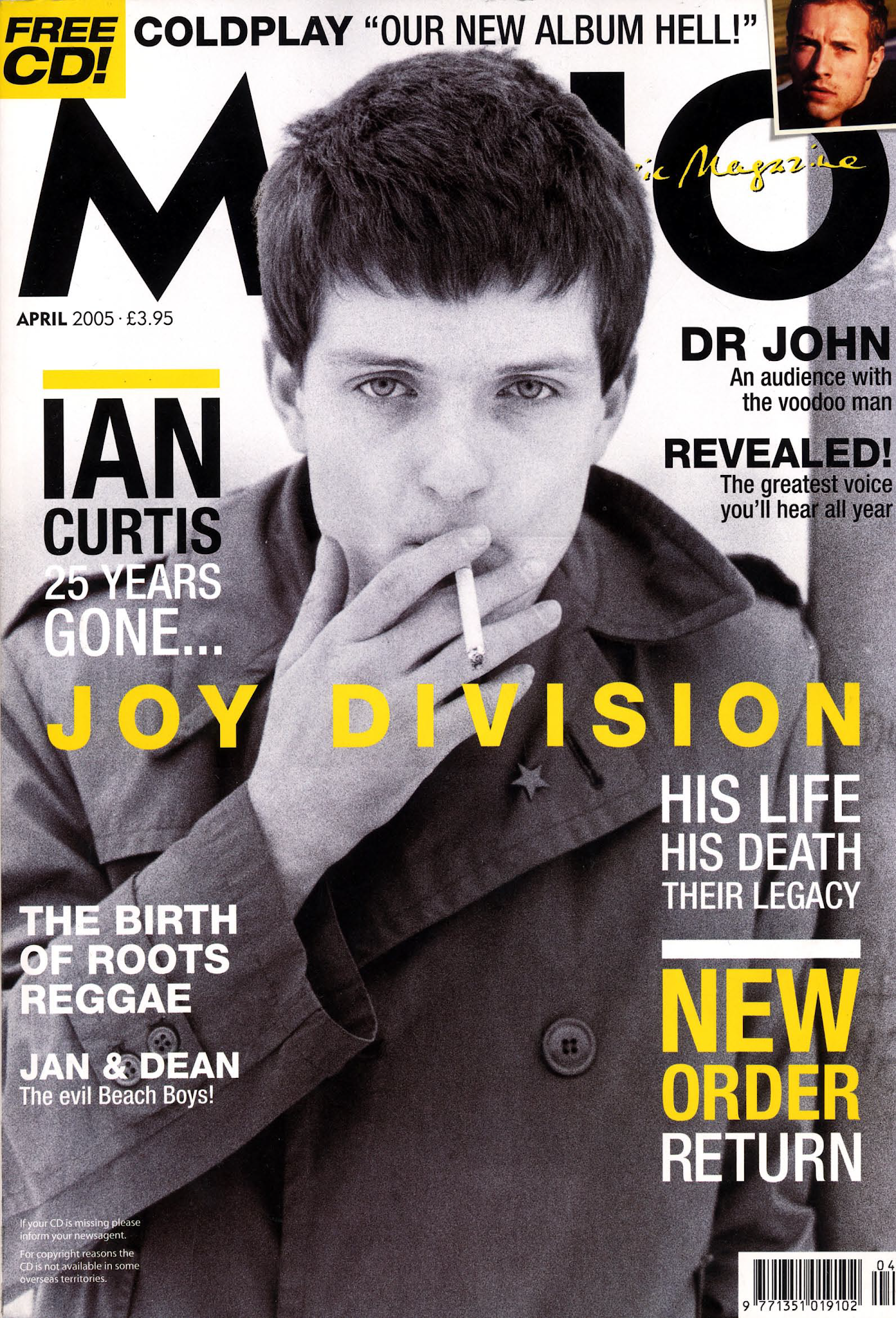

2005 04 Joy Division Mojo

THE OUTSIDER

Behind the steely myth and intense music, the Joy Division story remains a dark riddle wrapped inside the enigma of frontman Ian Curtis's early death. Pat Gilbert unravels a twisted tale of depression, black humour, infidelity and sickness.

IN OCTOBER 1979, JOY DIVISION CLIMBED into Steve Morris’s Olympic blue Ford Cortina and headed off on their first major UK tour. For the next six weeks they would be supporting the Buzzcocks at 2,500-seater venues across the country. Befitting a group on a small Manchester independent label, money was tight. Up north, they drove home after the gigs, feasting on the backstage booty of butties and crisps.

The damp autumn weather and lack of luxuries resulted in numerous muttered complaints. Yet, despite their austere public image, life on the road with Joy Division was never dull. In fact, it was pure Spinal Tap, with perhaps a dash of Coronation Street.

“We were like kids in a sweetshop,” grins Steve Morris. “They gave you a free crate of pale ale! It was our first encounter with The Rider.”

There were lots of hi-jinks. In Cardiff, the hotel bar shut at 2am, so the roadies prised off the metal grilles and handed out free beer, the night ending in a huge drunken cushion fight between main act and support. In Guildford, Joy Division surpassed themselves by removing the strip-lights from the gents’ toilets and smearing the taps and light switches with excrement.

During a mid-tour break, the group plaved a one-night stand at an arts complex in Brussels. After the gig — a significant landmark in the story for darker reasons — Ian Curtis got drunk and pissed into a free-standing metal ashtray.

The group were, by some accounts, a randy bunch. “There was suddenly this fantastic copping potential,” explains Morris. “1 was somewhat young and naive in that respect. It was like, ‘Steve, can I borrow the keys to the car?’ Why? i need to get some badges.’ Why do you need badges? ‘Look, just give me the fuckin’ keys, you twat!”’

“Ian Curtis was actually loads of fun,” stresses Tony Wilson, Factory Records boss and music biz legend. “They all were. Their major pastime was japing — it was a central part of their lives.”

But you can hardly blame the outside world for buying into the noir joy Division myth. Live footage from that time doesn’t exactly suggest four working-class, Northern lads out for a laugh. On-stage, they are intense, stern, apocalyptic. Ian Curtis, lost in his own world, marches back and forth like a demented Wehrmacht sentry, rhythmically clutching at imaginary ghosts. Peer closer, and his eyes are glazed and haunted. It’s as if he’s seeing something we can’t. Maybe he was. On that tour, he was suffering on-stage epileptic seizures virtually every night.

But talk about Ian as some kind of mystic and you will get very short shrift from his friends and former bandmates. Again and again, they will stress “he was just a normal bloke” — married, a child, a mortgage, a dog, lived in an ordinary terraced house, loved music. Some of those closest to him will admit there were occasional glimpses of a mysterious, secretive, unknowable Ian, someone who, as Peter Hook explains, “was trying hard to hide part of his personality”.

But that didn’t mean that his sudden death, 25 years ago, made any more sense.

WHEN IAN CURTIS HANGED HIMSELF AT HOME IN Macclesfield, Cheshire, in May 1980, he assured himself immortality. He was the second high-profile casualty of the punk era, following Sid Vicious’s overdose a year earlier. But the two couldn’t have been more different. Sid was a rock’n’roll psychopath who fell victim to his monumental stupidity. Ian Curtis — beneath his unassuming Northern front — was a gifted poet and original thinker, clearly battling a debilitating illness and the stresses of a messy personal life.

Within weeks of his death, Love Will Tear Us Apart, one of Joy Division’s last recordings, reached Number 13 in the chart. Its sorrowful melody and haunting lyrics, seemingly about his disintegrating marriage, brought the group, somewhat late for Curtis, their first mainstream recognition. Ian was instantly transformed into an archetype: a dark visionary, who knew his life was fated to be a short one. On closer inspection, it appeared that Joy Division’s lyrics foretold of his tragic end. When he wrote about death, on tracks like Dead Souls, Shadowplay and New Dawn Fades, it was as if he was so close to it he could already feel what it was like and was presenting his own suicide as his final artistic statement.

His bandmates probably chuckle at such portentous analysis. But there is at least one person in this story who believes that Ian may have been secretly and knowingly living out the existence of a doomed prophet: his wife, Deborah. “He used to fantasise about taking his own life, that romantic idea of dyingyoung,” she explains. “All the people he admired were ones who weren’t around any more. That’s what he wanted — to be like them. ”

It’s Christmas Eve 2004, and MOJO is discussing Joy Division’s enduring appeal with Tony Wilson. Today, the group seem to be hipper than ever. They’re becoming to a new generation what The Velvet Underground were to theirs: a deliciously dark, cultish pleasure. Tune into MTV2 and it’s awash with nervy young men who’ve clearly absorbed the group’s emotional, icy magic: Interpol, Kasabian, The Rakes, Snow Patrol, The Futureheads, Black Rebel Motorcycle Club...

Then there’s the film. In January, it was announced that an independent US production company is finally to bring Touching From A Distance, Deborah Curtis’s book about her life with Ian, to the big screen.

Tony Wilson is calling from his mobile. He’s in Salford, walking his dog, William — the pooch in New Order’s Blue Monday ’95 video. He is reassuringly as you’d expect. “Joy Division are immensely important,” he pants. “Bernard Sumner is... Hang on... William! Get off the road! Sorry about this... look you can’t shit there, you silly dog... William!!”

He rings off; he rings back. “Bernard Sumner is annoyingly clever,” he booms. “He once made the point that punk rock was vital because it rescued music from the crap and made it real again. But punk only had a limited vocabulary — it could only express simple things like ‘Fuck you!’ or ‘I’m bored’. Bernard said that sooner or later, someone was going to take the energy and inspiration from punk and make it express more complex emotions. And that’s what Joy Division did. Instead of saying ‘Fuck off’, they said: ‘I’m fucked.’ In doing so they invented post-punk and regenerated a great art form — rock’n’roll.”

Steve Morris: “It was very English, that suppressed emotion. It’s music for a race used to suffering in silence.”

STEVE MORRIS STILL LIVES IN MACCLESFIELD, THE Cheshire market town which used to spin silk for the world’s finest wardrobes. We’re sitting in the barn-cum-recording studio of his farm, where some of New Order’s forthcoming album, Waiting For The Sirens’ Call, was recorded. Pinned on the wall are instructions for making the group’s tea: Hooky “no milk”, Bernard “filtered water”, etc. In the corner is a full-size replica Dalek and piles of equipment, including some old Joy Division stuff — Bernard’s dusty Vox stack and Steve’s drum kit, stolen from outside New York’s Iroquois hotel in 1980 and later recovered during an FBI raid on a mafia warehouse.

Joy Division came together a few months after Curtis befriended Sumner and Hook at an early punk gig — no one can agree which one. Bernard and Peter were mates from Salford, the area of Manchester infamous for its cramped terrace houses and smelly textile factories. They’d been teenage skinheads and Mods, hanging out at North Salford Youth Club, listening to rock and soul. Hooky liked reading Richard Allen’s ’70s youth cult novels; Bernard was gifted at drawing but couldn’t afford to go to art school.

“Ian just seemed like one of us,” recalls Hook. “He had an Army & Navy flak jacket with ‘Hate’ written on the back. That was quite good. He was quiet and polite. Dead nice, really. He had a mate at college who painted doors on the floorboards. That’s Macclesfield for you! Then Steve joined. Did coming from Macclesfield make them outsiders? In a way. It was green hill and open spaces. They were both fuckin’ mad.”

Joy Division’s unusual sound developed during 1977 and 1978 at T.J. Davidson’s, a drab, ugly textile warehouse converted to a rehearsal space. Now demolished, it was situated on Little Peter Street, behind Deansgate Station on the fringes of Manchester city centre. In winter, it was so cold the group used to start fires with scavenged wood to keep themselves warm. The group — initially called Warsaw — practised for three hours every Saturday afternoon. All of them had day jobs.

Their originality stemmed from a punk naivete. “None of us could play a note,” explains Bernard Sumner. “So instead we decided to use our brains and intelligence to do something original. We learned to play within our limits. What we did was simple and powerful.”

“There was none of this ‘four bars of that’ malarkey,” grins Morris. “It was like, ‘Play that riff twice and then do another riff.’ We had no musical language at all. None of us knew what a bar was. We used to argue about it, ‘Hang on, that’s your idea of a bar, not mine.’”

Tony Wilson describes Warsaw, who regularly played Manchester’s punk venues — Electric Circus, Rafters — as a “fucking cacophony with a great singer”. Famously, Hook played melodic riffs high up on the neck of his bass because his equipment was so poor it was the only way he could hear himself. Their music was edgy and intense. In From Joy Division To New Order, Mick Middles posits the theory that the group may have unwittingly been funnelling the vibrations of T.J. Davidson’s grim, industrial past.

Sumner and Hook take the psycho-architectural link even further.

“My background was working class,” says Bernard. “I lived in Alfred Road with my mother and my grandparents. It was a Coronation Street-style house. My niece and aunties lived in the same road. There was a chemical factory at the end of the street, which backed onto the River Irwell. It stank. When I was 11 we were moved into a tower block. We thought it was great. It had a bathroom and an airing cupboard. But it was also the breaking up of that community. I thought everyone in the street would move into the same tower block, but they didn’t.”

Hook: “Where Bernard and I lived it was dark, it was the ’50s and ’60s, there was still smog, rows and rows of terraced houses. It was black and claustrophobic.”

“There was something subconscious in my mind,” adds Bernard. “The displacement and sense of loss I had... Then my stepfather died. I was quite angry. Up until I was moved to a tower block, everything was really good. Afterwards it wasn’t. I think that may have affected the music in some way.”

“Joy Division were from the north side of Manchester,” the group’s producer, Martin Hannett, explained to Martin Aston in an unpublished interview from 1989. “It’s a science fiction city. Not like the south side at all. It’s all industrial archaeology, chemical plants, warehouses, canals, railways, roads that don’t take any notice of the areas they traverse. The incidence of serious diseases in north Manchester is 50 per cent higher than anywhere else in the country. Grim, eh?”

In April 1978, Ian Curtis handed Tony Wilson a note at a local battle-of-the-bands contest, the itinerant Stiff/Chiswick Challenge, informing him he was a “fucking cunt” for not booking the band on his Granada TV show, So It Goes. Within a year the group had recorded an album, Unknown Pleasures, for Wilson’s new independent label, Factory a Records (no advances, no contracts). It was only when Martin Hannett —who based its sound on The Doors’ Strange Days — played them a test pressing that they properly heard what Curtis was singing about.

The lyrical content was blacker even than their music: death, religion, love, war. There were references to “the blood of Christ”, a girl’s uncontrollable seizures, childhood rooms filled with “bloodsport and pain”. His poetry was chilling, polished and original. Just as the group never analysed their music, no one ever asked Curtis to explain the words he sang in his rich, powerful tenor. It wasn’t as if Joy Division were consciously trying to preserve their own mystery. “Ian’s words sounded great,” says Hook. “That’s all that was important at the time.”

IT’S A WET, DRIZZLY NIGHT IN DECEMBER AND Macclesfield isn’t in the mood to give up its secrets. MOJO is trying to find the “monstrous” grey council block behind the town station where Ian Curtis lived as a teenager. After 40 minutes trudging around the perimeter of Victoria Park, I give up. It later transpires that Park View flats were demolished 18 months ago.

Deborah, Ian’s widow — who now uses her maiden name Woodruff — has fond memories of them. “I remember Ian standing on the balcony, wearing his sister’s pink fluffy jacket and eyeliner,” she smiles. “He was tall and imposing, over six foot, a little bit frightening. This was 1973. Did he ever attract trouble? No. He could give people the stare.”

We are sitting in a pub, the Station Hotel, opposite the railway station, looking out on Manchester’s old industrial centre, warehouses and textile factories now converted to posh flats and heritage museums. When it was first published 10 years ago, Deborah’s memoir, Touching From A Distance, gave the first intimate and detailed picture of the singer’s life. It was an intensely moving book. The film rights were quickly optioned. Now a pair of young US producers, Orian Williams (Shadow Of The Vampire) and Todd Eckert (a music journalist-turned-financier), are bringing the story to our cinemas. Photographer Anton Corbijn, famous for his iconic images of Joy Division, U2 and R.E.M., will direct. The working title is Control.

“I don’t think there are that many really great stories out there, but this is one of them,” explains Eckert enthusiastically, during a visit to MOJO’s local. “Debbie doesn’t want a candy-coated version of events, or something simply designed to sell the catalogue. This will be the honest, legacy-defining document.”

Ian Curtis was 16 when Deborah first met him. A bright grammar school boy who’d passed seven O-Levels, he was also a pharmaceutical adventurer (solvents, Valium, barbituates) and music nut (Lou Reed, Bowie, MCS, Iggy). His interest in drugs got him expelled from school — where Steve Morris was in the year below. Ian’s father worked as a detective in the Transport Police: it’s from him that Ian apparently inherited his love for literature and “silent moods”. Though living at 11 Park View when they began courting, Curtis was actually brought up in Hurdsfield, on the outskirts of Macclesfield.

“From what I can tell it was a fairly idyllic childhood,” says Deborah. “Wandering around fields, building dams in brooks, chasing pigs. It always puzzled me why he was so obsessed with writing about cityscapes. Maybe he felt guilty that he wasn’t trapped in one. Ian was angry,” adds Deborah. “But I was never sure why.”

Deborah found Ian charismatic and attractive. He was highly creative and original, and kept box files full of poems, lyrics and stories. He often stayed up late writing. He was desperate to make it as a rock star. Deborah recalls that he was smitten with tragic figures like James Dean and Jim Morrison; he also, she says, entertained romantic fantasies of his own early death.

He read Hesse, Sartre, Ballard, Dostoevsky, sought out cult films by Herzog and Fassbinder and, like most youths of his generation, was fascinated with Nazi Germany and military history. (Hence ‘Joy Division’, the corps of Jewish women forced to pleasure SS officers in the concentration camps.) Later, when Joy Division was taking off, Ian privately corresponded with Genesis P Orridge from Throbbing Gristle, punk’s foremost avant-garde thinker and outre performer.

“He was really clever,” she explains. “He could have done something very cerebral. He was a fantastic writer and had plans for various works. It’s a loss in that way. His lyrics are fantastic — imagine if he wrote a novel...”

Intelligent though he undoubtedly was, the man Deborah describes in her book isn’t always likeable; nor is he standard-issue rock’n’roll material. His politics were to the right. In 1975, he voted Conservative and insisted Deborah did the same. Though caring and tender, he could also be insecure, possessive and controlling. According to Deborah, she agreed to their marriage in 1975 under duress: Curtis made vague threats that he might do something to himself if she turned him down.

At their engagement party Ian violently threw his Bloody Mary over his fiancee, believing she was flirting with an uncle. Later that evening, she saw Curtis dance for the first time — the awkward, weaving shimmy the world now knows so well. She didn’t think it unusual at the time.

Once married, Deborah often found it hard to talk to her husband about his poetry and deeper thoughts. “He didn’t communicate very well,” she sighs. “You never knew what his agenda was.”

He got a job in a Manchester record store and was an early convert to punk. When he met Sumner and Hook he had the means to channel his literary ambitions and rock star dreams into something real.

Throughout 1978 and ’79, when the group was taking off, he worked hard to keep his domestic and band life together. He took his new job, at the Manpower Services Commission, seriously. He and Deborah were so strapped for cash he even cleaned the group’s rehearsal room for a few extra quid. When Tony Wilson co-opted Joy Division to glue together the sandpaper sleeves for Durutti Column’s Return Of The... LP the rest of the group paid Ian to do theirs for them. Meanwhile, they sat and watched a porn film.

In social situations Ian was witty and good company He was also capable of being provocative, especially after a few drinks. In her book, Deborah mentions being upset when she heard that Ian had entertained the band with an offensive story about a Pakistani family defecating into sheets of newspaper and hurling the parcels into a neighbour’s garden.

There was, it seemed, a disturbing and unfathomable side to Curtis. It was only seen occasionally, but it was, says Morris, like “someone had flicked a switch”. His first encounter with “alter-Ian” came not long after he joined the group, and they all went to see The Stranglers at the Electric Circus. “We couldn’t get in, so we went to the pub,” Morris explains. “The Stranglers’ drummer, Jet Black, was in there smoking a pipe. So Ian said, ‘Look, I’ll go over and sort us out.’ He was drunk [and] the next thing was like, Where’s Ian gone? Then I saw him necking with some bird I’d never seen before in me life! It was like, What?! I said, Do you know her? He said, ‘No. ’ So Ian is wearing a black star on his lapel and goes up to [journalist] Paul Morley, who says, ‘That’s a fascist symbol’, and Ian says, ‘No, it’s not, Paul, it’s anarchy, FUCKING ANARCHY!’ Then Ian said, ‘Shall we go into the ladies bogs?’ And I was like, Ladies’ bogs? Erm, why would we want to? It was frightening. He did like to carry on with the ladies.”

“Ian did have a bit of Jekyll and Hyde thing,” agrees Sumner. “I remember he tried kicking in the door of the dressing room at [the Stiff/Chiswick Challenge] gig, when Paul Morley and Kevin Cummins were taking ages to come on-stage. He [once] got so wound up arguing with Rob Gretton he ran around shouting with a bucket on his head. I thought it funny more than anything else.”

Outside the group, Ian and Deborah enjoyed a fairly ordinary domestic life. At weekends, they would take country walks with their dog. In April 1979, the Curtises became a trio when a daughter, Natalie, was born. His existence was, in many respects, the paradigm of normality. I put it to Hooky that Curtis — and Joy Division — weren’t very rock’n’roll in comparison with The Clash and Sex Pistols, who lived in squats, stole their food from street markets, and led a bohemian, art school life. He bristles. “Ian was a working-class bloke who had to go out and earn a living,” he says. “We all were. All those other bands you mention were middle-class and had money. We had nothing, it was totally derelict where we came from in Manchester. Ian had responsibilities, he struggled hard to feed his family, even though he’d rather have played music all day.

“I think that makes him more rock’n’roll. Don’t you?”

IN OCTOBER 1979, WITH A NEW SINGLE, TRANSMISSION, out, the group set out on tour with the Buzzcocks. By now, Unknown Pleasures, was a permanent fixture on the indie album chart. In Sounds, Jon Savage proclaimed it to be “one of the best, white, English debut LPs of the year”.

The Buzzcocks’ Steve Diggle remembers the group as “very reserved. I don’t know if we frightened them off because we were pissed up and full of drugs. We had a different verve and spark. It was rock’n’roll. They seemed reticent and timid.” Many claim that Joy Division’s deeply emotional, sheet-metal roar blew the ’Cocks off the stage. (Diggle, not surprisingly, dismisses such talk: “Another Factory myth. Most of the audience were still in the bar when they played. We were louder, heavier... No, quite impossible.”)

On October 16 the group journeyed on their own to Brussels Raffinerie du Plan K, an old sugar refinery converted into an arts centre. The evening culminated in a reading by beat legends Williams Burroughs and Brion Gysin from their collaboration The Third Mind. “To be honest, we all liked that kind of stuff, but we didn’t go on about it,” says Morris. “We didn’t go around in black or wearing sunglasses inside. But occasionally he would reveal that part of himself. I remember he went smooching over to Burroughs. We were like, ‘Great, we’ve got a crate of double-dead-strong beer, can we get another? ’ He was off getting his book signed. ”

Later, a drunken Ian reverted to type and pissed into the aforementioned metal ashtray. When a member of staff remonstrated with him, he sarcastically addressed her in slow, loud English, like a stu-pid-foreign-er.

The constant touring and exhilaration of being the music press’s bright new promise was beginning to adversely affect Ian’s health. At the end of the previous year, in December 1978, he had suffered his first epileptic seizure, following Joy Division’s first ever London gig, at the Hope & Anchor in Islington. He had been prescribed medication, but the attacks were becoming ever more frequent, more violent. On a couple of occasions, Diggle recalls that the Buzzcocks were asked to extend their set, so fans wouldn’t interfere with ambulance crews trying to reach Ian backstage. The seizures usually occurred either on-stage or directly after performances.

Soon, however, there would be another stress that would send Ian’s epilepsy spiralling out of control. The last night of the tour, at the Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park, Steve Diggle was chatting at the bar when Ian approached him. “We were talking generally about it being a good tour, how everything had gone really well, etc,” he recalls. “Then Curtis said, ‘I’ve got this problem. I met this girl in Europe and I’m married with a kid.’ He said it in a very sensitive and troubled way. That sort of thing was happening to a lot of people around us at that time. The temptations of the road. I just said, Don’t worry, mate. You’ll get over it! Other blokes would have laughed about it, but Curtis didn’t. It seemed to be a real problem. I didn’t realise how much of a problem.”

WHEN JOY DIVISION SPED off down Ian’s street to start their European tour on January 10, 1980, Curtis looked directly ahead and didn’t wave goodbye to Deborah. Annik Honore, the girl he’d met at Plan K in Brussels, would be secretly accompanying him throughout the tour. None of the other band members had a wife or girlfriend in tow. Annik worked at the Belgian Embassy in London. She was, by all accounts, “blonde, glamorous and exotic”.

On the road, the usual pranks and japes prevailed. “In Cologne, I did the stupidest thing that I’ve ever done,” says Morris. “We quite liked speed at the time. We sent someone to get some, and he came back and said, ‘I’ve got you this.’ It was like this red star.”

“It was called a Belgrade Star,” clarifies Peter Hook. “Steve swallowed it. This guy was like, ‘On no! Dat is five hits of acid!’ He took the lot in one go. Steve was out of his mind for two days. We were staying in a loft space, 12 feet up. Twinny, our roadie, thought it would be amusing to take the ladder away for the night.”

Morris: “I spent the rest of the tour tripping. I kept shouting, I’m going to chop off your head with an axe!”

Having Ian’s girlfriend/mistress travelling with them inevitably caused tensions. “I liked her,” says Hook. “But she was very bossy and domineering. The funny one was staying in a brothel. I can’t remember where. Speakers under the bed. You hired it by the half hour. After the gig we were in the van outside, waiting to go in. Annik said, ‘Hang on, ziz is a knock-ink shop!’ Yeah, so what? She said, ‘I am not staying in an ’ouse of ill-repute.’ So we said, Look, you’re shagging a married bloke, so what the fuck are you talking about, you silly cow!”

Outwardly, Curtis didn’t seem fazed by what was clearly an awkward situation. However, once the tour had finished and he was back home with a suspicious Deborah in Macclesfield, there was a sign that he was deeply troubled. One night, he drunkenly sought out a Bible. Having studied religion at school, he knew just where to look. He gouged out chapter two of The Revelation Of St John The Divine. It concerned the wanton Jezebel: “Behold, I will cast... them that commit adultery with her into great tribulation.”

Later, it transpired that that same night he’d cut himself up, too. Unbeknown to anyone, Ian’s life was entering its final phase.

Between March 18 and 30, 1980, Joy Division worked on a second LP. As with Unknown Pleasures, the producer was Martin Hannett. As ‘Martin Zero’, Hannett had recorded the Buzzcocks’ pioneering Spiral Scratch EP, and it was this thick-set and dishevelled figure who had transformed Joy Division’s raw, edgy live sound into the glassy, stately, controlled force on Unknown Pleasures.

The sessions took place at Pink Floyd’s studio, Britannia Row, in Islington. Meanwhile, the group were billeted in a pair of adjoining flats in a modern residential block off Marylebone Road. New to London, each afternoon they’d go sight-seeing. Britannia Row had several superb, ambient ‘live’ rooms. Hannett— a casual heroin user who regarded himself as an artiste — chose the location because, according to Steve Morris, he “liked to record in places that had a history of success”.

“Martin’s method was to turn everything upside down,” says Hook. “He talked to you like a mad professor. He’d say, ‘Make it softer but harder. Wider but not too wide.’ Jesus, it’s a only a fucking bass line, Martin! He had his head in the clouds. But he managed to bring a bit of the heavens down to earth. He managed to capture something special.”

“If Hooky has been able to communicate to me what exactly it was that he wanted, instead of saying it wasn't what he wanted, it would have been easier,” said Hannett in 1989.

Steve Morris: “I thought Martin was great. The analogy was the Tom Baker Dr Who. It was a double-act between him and Chris Nagle, his assistant. If we tried to interject, it was like, ‘Hmm, musicians...’ It was quite us-and-them. You sometimes felt you were on the outside of it all. The way you pushed the buttons on the console was all part of the recording magic, apparently. Right on, Martin!”

Sumner: “Martin had a vision, but it was difficult to see. He could hear things in the music that no one else could. Whether it was because he was stoned, I don’t know. We used to say, Tell him to turn up the ARP [synthesizer], and Hooky would say, ‘Martin, can you turn up the ARP?’ And he’d shout, ‘What?! What are you fucking talking about, you fucking cunt?!’ He’d get really angry. But it was S0/50, we got our way half the time.”

Closer, as the album would be titled, was carefully constructed from numerous performances and overdubs. Each drum was recorded separately. The music clearly foreshadows the beautiful, wintry, electronic dance music of New Order. Hannett insisted they used synthesizers and electronically triggered drum beats with which he’d become fascinated. (“Listen to The Eternal,” rails Morris, “there’s actually a beat missing because the equipment didn’t fucking work! ’)

Ian’s voice was growing richer and more expressive — thanks, Tony Wilson believes, to a conversation he and Curtis had recently had about Frank Sinatra’s tone and phrasing. The most startling aspect of the record, however, was Ian’s lyrics. With hindsight, Closer clearly reveals his troubled inner life and anxieties about his physical deteroriation. Atrocity Exhibition, though ostensibly about the Nazi extermination camps, seems also to relate to his own experiences on-stage — an epileptic freakshow. Heart And Soul ruminates on the struggle between right and wrong and ultimately expresses an indifference to living. Love Will Tear Us Apart — taped at this session (but not on the album) — speaks of two lovers, reluctantly and painfully journeying on different paths.

Martin Hannett: “I’d rather still have Ian alive but it was just perfect. It was a document. He was crumbling. But it all came together in a magical way. There’s just a lot of pain in there as well as pleasure. Ian wasn’t taking his medication because he felt like it made him numb. He had to be looked after very closely all the time, because epileptics get prescribedfistfuls of phenobarbitone. These turned him off it slowed him down. On the few occasions that we couldn’t look after him, we’d find him in a mess, because he’d had a fit. Sound-wise, I invented all these little tricks to do with generating sound images, like a holographic principle. Light and shade. Trying to make it independent of what you’d then listen to it on.”

Meanwhile, the japery continued. Ian was living with Annik in the bedroom of one of their Marylebone apartments. “It was trying to be a model of domestic bliss,” recalls Steve. “(Belgian accent) 'Ian, are you do-ink your i-ron-ing?’ It was like, ‘Tell her to fuck off!’

“One day we found this kebab shop,” he continues. “It was like, Great! We said to Ian, ‘Come on, let’s go in! ’, and Annik looked daggers at him. He said, ‘No, Annik’s a vegetarian.’ And she said, ‘And zo are you, Ian!’ So he’s like, ‘I don’t like kebabs.’ And we’re like, You what?! You don’t like kebabs?!... OK, have a salad, then. I’ll have a doner kebab — actually, I’ll fucking well have his.”

The group wound up the couple by folding their sheets into an “apple-pie” bed that you couldn’t get into, and removing all their furniture bar the “i-ron-ing board”.

‘“It was a bit tense,” says Sumner. “Partly because of Annik’s presence. Rob and Hooky took the piss out of Ian. I thought it was a bit out of order, actually. But Ian was being a different person in front of Annik. You don’t fart in front of a new girlfriend, do you? So I think everyone had had enough of it. But... I don’t want to open old wounds.” Annik, who now lives in Belgium, didn’t respond to our request, via an intermediary, for an interview; she has never given her account of events.

The last few months of Ian Curtis’s life is harrowing stuff. The most significant developments were his affair with Annik and worsening epilepsy. During the Buzzcocks tour, Ian had been suffering seizures virtually every night: they’d become almost a perverted validation of Joy Division’s Sturm und Drang. During the early months of 1980, the fits became more violent. At home with Deborah, he couldn’t fall asleep until he’d had an attack. The stress of his complicated private life clearly wasn’t helping. Nor was the primitive treatment for his epilepsy. The carbamazepine and phenobarbital prescribed to controlled his seizures resulted in unpredictable mood swings, “like a drunk, but without the high”, according to one leading epilepsy specialist. Ian was becoming extremely ill.

In April, Joy Division supported The Stranglers at the Rainbow. Curtis, lost in his dance/trance, had an epileptic seizure on-stage. Later that night, the band drove across London to headline a Factory Records show at the small Moonlight Club in West Hampstead. Ian had another fit while performing. Afterwards, he sat at the side of the stage, a complete wreck.

Ian stayed in London with Annik. On Easter Monday, he finally returned home to Deborah. That night he attempted to take his own life, with an overdose of phenobarbitone. He was rushed to hospital to have his stomach pumped. When Ian was discharged, Tony Wilson suggested he should stay at Wilson’s cottage in Glossop.

With hindsight, Joy Division should have taken a break. Despite the group’s reservations, Ian agreed to honour a gig the very next evening at Derby Hall, Bury. Knowing he was unwell, Rob Gretton arranged for Ian to perform just a handful of songs, then hand over to A Certain Ratio’s Simon Topping. The audience was outraged. The gig ended in a huge brawl.

Ian was devastated. Wilson found him upstairs in tears.

“We were young, and the band was taking off,” says Hook. “We’d worked so hard to get that far. We didn’t know to deal with Ian’s illness. Imagine four 22-years-olds from Manchester —it was like, Hi, Ian. ‘Hi. Look, I’m really ill.’ Right. (Pause) You up for a pint then? It wasn’t like, OK, let’s sit down and talk about it. But let me make it clear, we did look after him. But the thing was he didn’t do much to help himself. He was fighting it.”

Steve Morris: “If we were more caring we could have dealt with it better. But we were like, He’ll be all right! He had to go to bed early, not get drunk, lead a regular lifestyle. No flashing lights! Don’t flash the lights! We were actually quite careful about that. But that was the antithesis of what he was. He wasn’t the kind of person who went to bed early. It was a head-fuck. Being in a band wasn’t conducive to making a recovery.”

A few days later there was a band meeting. Ian said he was leaving: he was going to Holland to open a bookshop. The group said fine. The next day Curtis met Sumner in the street in Manchester. He acted as if the conversation had never happened. The only talk was of rehearsals and gigs. Ian’s life was accelerating towards its grim conclusion, though nobody suspected it. A tour of America was booked for late May. Estranged from Deborah, who wanted a divorce, Ian stayed with Bernard before returning to his parents’ house.

It was around this time that a bizarre and chilling event occurred: Bernard was interested in hypnotism and agreed to put Curtis under. “Ian brought the tapes home for me to listen to,” says Deborah Curtis.“ [He] insisted he had regressed to a previous life.”

Todd Eckert, a producer of Control, has heard a cassette of the session. “You’d presume they were messing about, but they weren’t,” he says. “They were really serious. When Ian goes under he becomes this guy living in a hut in France in the 17th century. The intensity with which he tells this story is astonishing. It’s the single most scary thing I’ve ever heard in my life. Why? (Pause) Because Ian is alluding to already being dead.”

JOY DIVISION’S LAST gig was at Birmingham University on May 2, s 1980. During the next two weeks, Ian Curtis didn’t have any serious seizures and seemed quite content. “It was Friday night, we’d been to Manchester, and then Ian said, ‘Drop me off at Amigos’, a Mexican restaurant we used to go to,” recalls Morris. “He was probably meeting some birds! Seriously. It was like, See ya! We’re on our way to America! Seeya!”

In Ian’s internal, heavily medicated world, however, things may not have seemed so cheery. On Saturday May 17, Curtis was meant to go water-skiing in Blackpool with Bernard, but didn’t. That evening, he spent the evening at the house in Barton Street, Macclesfield. He wanted to watch the Werner Herzog film Stroszek, and didn’t think his parents would appreciate a movie about three low-life Berliners re-locating to the US for a better life. The American Dream turns out to be a bitter lie; Stroszek kills himself. Deborah returned home from her bar job in the early hours of Sunday. She and Ian argued and Deborah spent the night at her parents’ house. The following morning she returned to find her husband’s lifeless body in their kitchen. He had hanged himself from their floor-to-ceiling clothes rack. Iggy Pop’s The Idiot was still spinning on the turntable.

Steve Morris: “Hooky phoned me on Sunday morning. He said, ‘It’s Ian. He’s only gone and done it.’ I said, Not tried to kill himself again? ‘No, he’s actually done it.’ I thought, It must have been an accident! He’s not clever enough to have killed himself. I felt angry with him. It’s the ultimate cop out.”

Inevitably, the feelings of those closest to him are coloured by their own attitudes towards suicide. Most are baffled by his actions, prompted as they were by his medication and unfathomable, hidden bouts of depression. “I didn’t understand it,” says Sumner. “We had no idea he was going to do it — if we had we wouldn’t have let him out of our sight. But... I’ve seen someone clawing to keep hold of life when they were dying of cancer. To throw something that special away... ”

Hooky (affectionately): “I thought, You silly bastard.”

CLOSER WAS RELEASED IN JULY 1980 AND REACHED Number 6. Its clattering, intense, funereal beauty took on extra resonance with Curtis’s death, the words of Love Will Tear Us Apart now seeming unbearably poignant. The phrase was chosen for Ian’s memorial stone in Macclesfield Cemetery and Crematorium.

Back in the Station Hotel, Deborah Curtis admits there are still many unanswered questions surrounding Ian’s death. “I know he fantasised about [dying young], but it’s still hard to believe that he actually went through with it. All kinds of things go through your mind: was he just messing about in the kitchen? Was it an accident, did he have a fit?”

I ask her what Ian would have thought of being a MOJO cover star and the subject of a film. “He’d love it!” she laughs. “Really. That’s what he really wanted and dreamt about. I can’t understand that he wanted something so badly that he had to die for it.”

“It doesn’t bother me that Ian’s become a rock martyr,” insists Bernard. “He was so good at what he did, a great performer, great lyricist, great singer. It’s fantastic that he’s remembered. That’s why we now play Joy Division songs.”

“We’ve had a great time,” concludes Hooky. “I just wish Ian had stayed around to enjoy it.”

Thanks to www.worldinmotion.com. Matthew Norman at Manchester District Music Archive (mdmarchive.co.uk), David Sultan at Worldinmotion.net, David Walther at IanCurtis.org, and joydivisioncentral.com, Matthew Swinnerton of The Rakes and Martin Aston for the use of his Martin Hannett interview.

=======================================================

THE PRODUCER

The crackpot genius of Factory legend Martin Hannett. By Martin O'Gorman.

MARTIN HANNETT dropped out of a chemistry degree at Manchester Polytechnic to become the most influential figure on the city's post-punk scene. After promoting local bands and some notable studio work including the Buzzcocks' Spiral Scratch EP, he was first choice to produce Joy Division's contribution to the Factory Sampler in 1978 and soon became the label's in-house producer. His methods were notoriously eccentric but it was his ability to create remarkable soundscapes that led to commissions from U2, Magazine and many more in the ’80s. As producer, Hannett opened up a world to Joy Division far beyond their stage sound. Using new technology and startling innovation, he enabled Unknown Pleasures to inhabit its own sonic universe - the compressed drums and ambient noises propelling the band light years from their punk roots. Despite critical acclaim, the band hated it, claiming it was "unrepresentative" of their live sound. "They were a gift to a producer," Hannett told Jon Savage in 1989, "because they didn't have a clue."

However, said working methods were the undoing of his relationship with New Order. "I'd never in my life desired to become a singer, but we couldn't replace Ian with a stranger so one of us had to do it," explains Bernard Sumner. "I needed a lot of guidance [and] I remember working on the track I.C.B.... and Martin went, 'It's not right, do it again.' And I was like, Why, what am I doing wrong? He went, 'It's just not right, just keep doing the song and I'll tell you when it's right.’

"So I didn't speak again, I just sang it and sang it. I must have sung it 40 times. And then I thought, Oh fuck, I've had enough of this and I went in the control room and there was no one there. He'd gone. Just disappeared. Fucking twat.”

The death of Ian Curtis hit Hannett hard and New Order's dissatisfaction with Movement led to a parting of the ways. Factory's investment in the Hacienda rather than studio equipment was the last straw and in April 1982, Hannett sued Factory over monies owed.

"If you're a masonry drill, you eventually become slightly blunted," he told Martin Aston in 1989. "I found it necessary to go away, after my fight with Factory. I went back to my 8-track in my bedroom for a year."

Slipping into a rapid decline thanks to a long-term romance with heroin, Hannett rejoined the Factory family in 1988 to produce Happy Mondays' Bummed. Having produced a number of new Manchester bands including The Stone Roses, he died on April 18, 1991 of heart failure, aged 41.

Extra material by Pat Gilbert, Ann Scanlon and Martin Aston.

=======================================================

THE SVENGALI

Tony Wilson: the self-confessed "twat" / label boss behind Joy Division and New Order talks to Pat Gilbert

"IN 24 HOUR Party People Steve Coogan plays me as an affable clown, but missed out the twat," says Tony Wilson. “I very frequently talked to people in an unpleasant way and behaved like a complete cunt."

Born in Manchester in 1950, Anthony H. Wilson may be a self-confessed "twat" but he’s also arguably the most important music business honcho to emerge from the north of England since Brian Epstein. He may even be the single most influential UK label boss of the last 30 years. Via Factory Records, he brought us Joy Division, New Order and Happy Mondays, but in fomenting an original and exciting scene in Manchester, also The Smiths, Stone Roses, indie-dance music, Ecstasy and Oasis. Most importantly, though, he demonstrated that the music is at its most exciting when created, released and promoted by a bunch of neophytes and crazies.

Wilson was the son of a Salford tobacconist, but was brought up in Marple, near Stockport. A brazen selfpublicist with a rigorous intellect, he established himself in regional TV after graduating from Cambridge with an English degree. There was always something of the John Noakes about him, as Granada viewers in the North-west came to learn. The opening scenes of 24 Hour Party People, where he manfully crashes a hang-glider into a hillside, were based on a real broadcast.

Bored with Top Of The Pops, he created Granada TV's regional alternative, So It Goes, bringing us memorable early performances by the Sex Pistols, Clash, Siouxsie and the Buzzcocks. A night of Manchester acts (including Joy Division) at Rafters in April 1978 provided the germ for Factory Records - the following year he used a modest inheritance to fund Joy Division's masterful Unknown Pleasures. There were no contracts, advances or solicitors involved. The '80s saw New Order become massive, and Factory become home to cult acts like Durutti Column and Wilson's favourites, A Certain Ratio. The decision to sink the profits from New Order's records into the Hacienda club (the group were Factory shareholders) ultimately led to Factory's demise in 1992. But not before 'Madchester' had become musical phenomenon.

Factory's impact on Manchester is incalculable; Wilson sees it as part of a larger regenerative force beginning with punk. "We were the north of England, the thing was fucking finished - it was black, grey, grimy, boring and shit, and because of that when Richard Boon [early Buzzcocks manager] brought the Pistols to Manchester it set in motion this whole process. As Jon Savage once said, Manchester became the punk city, it took punk to its heart, and the genius of that music and how it moved into Joy Division and The Smiths and everything else was the engine of the glorious example of northern rebuilding that's Manchester today."

Still passionate about music, Wilson launches a new label, F-4, this month. First release - hip hop outfit Raw T.

=======================================================

THE MANAGER

Rob Gretton: pure class. By Ann Scanlon

"JOY DIVISION were a great band," says Tony Wilson in the commentary to Michael Winterbottom's 24 Hour Party People. "But they were Rob's band. Totally." Robert Leo Gretton was born in Wythenshawe and had two main passions: Manchester City and music. By 1977, he had become a central face on the Manchester punk scene, as a roadie for Slaughter And The Dogs and the editor of their fanzine, Manchester Rains, and as a regular DJ at Rafters. It was while DJ-ing there in June 1977 that Gretton first noted the nascent Joy Division. "I just thought they were the best band I've ever seen," he recalled later. On April 14,1978, the two London independent labels. Stiff and Chiswick, held a 'battle of the bands' night at Rafters - also attended by Tony Wilson. After watching Joy Division, Gretton became determined to take his interest further. Shortly afterwards, chancing across Bernard Sumner in a phone box outside Manchester's main post office, Gretton asked him if Joy Division needed a manager.

"In the early days Rob was our biggest fan and he really wanted us to succeed," says Steve Morris. "He would just say, 'Get in there and do it.' That was his style of management."

As the manager of Joy Division and later New Order, Gretton was a central figure in the rise of Factory Records and it was his idea for the label to open its own nightclub, the Hacienda (according to local folk lore, because he wanted somewhere to "ogle birds"). "Rob had a very anarchic way of working and he was very important in giving Factory and the Hagenda its class," says Peter Hook. "Rob was the style maker, if you like, and Tony was the frippery. Tony was cerebral, but Rob had the street suss and the chic."

Aside from his involvement in Factory Records, the Hagenda and the Dry bar, Gretton set up his own label, Rob's Records, which scored a Top 3 hit in 1993 with Ain't No Love (Ain't No Use) by the dance act Sub Sub (who would later evolve into Doves).

In 1998 Gretton was instrumental in getting New Order to re-form following a five year split. But on May 23,1999, he suffered a heart attack and died, aged 46.Those who knew Gretton remember him as a warm, generous, funny, honest and inspirational man, who was played with uncanny precision by Paddy Considine in 24 Hour Party People. "Rob used to say to everyone, ‘What are you doing?' Nothing, Rob, nothing.'What should you be doing? Skin up!'," says Bernard Sumner. "I'll remember those words."

=======================================================

THE SONG

The enduring mystery of Joy Division's Love Will Tear Us Apart. By Martin O'Gorman

JOY DIVISION'S most successful song, written by Ian Curtis as his marriage ran into problems and his epilepsy worsened, seems to sum up the despair at the heart of a too-short life. A lament for the death of a relationship, cut through with the dazed disbelief that "something so good... just can't function no more", the tone is more in sorrow than in anger, reworking the existential "it's-over" Sinatra ballad, crossing into such uncharted torch-song territory as desperation and deep resentment, an elegiac synthesizer line leaving the track on a curiously unresolved note.

Written by around August 1979, the song - immortalised in a John Peel session the following month - swiftly became a live favourite. But for a composition that apparently emerged fully formed, it was a struggle to get it on vinyl. The initial, faster version recorded at Pennine Sound Studios in January 1980 was deemed unsatisfactory, so they tried again at Stockport's Strawberry Studios in March and finished at Britannia Row during the Closer sessions later that month; slower and more graceful, Curtis's vocal impeccable. It's said he borrowed a Sinatra LP from Tony Wilson to prepare himself.

The band couldn't decide which was the better take, so Factory released both on the same single. Sensing a hit, a video was shot on April 28, 1980, but a Musician's Union strike blacked out Top Of The Pops when the single charted at Number 13 in June 1980. By then, Curtis was dead and the title literally became his epitaph on his memorial stone in Macclesfield Cemetery.

But Love Will Tear Us Apart would not die. The song sneaked into the public's consciousness again in 1983. New Order's success with Blue Monday led many newcomers to investigate the band's history and the song was covered by Paul Young on his landmark pop-soul debut No Parlez. "We were looking for modern songs to reinterpret," remembers Young, "and [producer] Laurie Latham said, 'Do you know this?' Once you see the lyrics written down you realise how powerful they are and how they could be reinterpreted as a soul song, so we put the the chord progression ofThe FourTops' Reach Out, I'll Be There underneath... next thing we know it's getting all this press and the label wanted to release it as a single. I remember when John Peel played it on his show he said, There's been a lot of talk about this song, but I'm just going to play it.' Afterwards all he said was That's a different version of a truly great song."' That year New Order performed the song live for the first time and the single was reissued in October, reaching Number 19 in the UK charts.

Nominated for Best Song OfThe Last 25 Years at the 2005 Brits [Robbie Williams' Angels won], there have been numerous covers.The song's greater impact lives on in the narcissistic lyricism, self-loathing and self-awareness of any number of alternative rock acts, ranging from Nirvana to to Antony And The Johnsons, "It's definitely one of the greatest songs of the last 25 years," asserts Paul Young. "It's like Tim Hardin's Reason To Believe, a beautiful song that comes from a place of great darkness."

=======================================================

THE FANS

Shaun Ryder

"Pips, on Fennel Street, was the coolest club in the 70s, 11 dancefloors, nine bars. We'd be in the R&B room, where all girls we fancied were, in casual gear, V-necked baggy jumpers, spiky hair... then all of a sudden, you'd hear that guitar from the other room, du-du-du du-du-du, all the lads would fucking leave the room, and go dance to Transmission. You felt like you and your crew could fucking slash the world. Forget the long macs, Joy Division was something absolutely different, darker. Hooky had a side parting and a beard. They were the only band that looked like one of the lads, what we call Perry scally, casual.

"I never met Ian Curtis. After school I got a job as a telegram boy [and] one day the gaffer said, 'Your mate's dead. That band you like, Joy Division, Ian Curtis is dead.' Fuckin' hell, that was heavy. It was an excuse to throw a bin through a fucking shop window. It was like your football team had lost.

I grew up with The Beatles, Stones, punk, but Joy Division made us pick up our instruments. Ask me about other bands, and I can talk, but Joy Division... fuck, I don't know why I can't say much. Sad?They didn't make me feel sad. Flow did they make me feel? Cool as fuck."

Ross Millard / The Futureheads

"I got into Joy Division through the Permanent compilation in 1995. I was only 13. My friend's older cousin had the Love Will Tear Us Apart 7-inch and the sleeve really struck me. So bleak - the complete antithesis of the forced jollity of Britpop: bands in fishing hats and camouflage jackets playing Les Pauls. Then I saw them on that BBC documentary, Dancing In The Street, cold blue lighting falling on Curtis. The button-up shirt, smart trousers, vacant expression. I'd never heard music so paranoid, claustrophobic, this overall identification with desperation and insanity. Otherworldly. Bookish. Enigmatic. Great fashion sense!

"She’s Lost Control is my favourite. The way the bass line dictates the song. The asylum vibe. The guitar being just part of the puzzle. Curtis would listen to Bernard's guitar parts, and move them around, so that the verse often becomes the chorus or vice versa. It's interesting when the vocalist and lyricist doesn't play an instrument because they often come up with this alternative, way of looking at things. I just can't get enough of Joy Division. Even knowing he was listening to Iggy Pop's The Idiot when he committed suicide inspired me to listen to that. On one hand, what a waste. At the same time, what a legacy."

Moby

"I grew up poor in a very wealthy town, Darien, Connecticut, where everyone was tall and healthy. My refuge was books, music, artists who gave a creative voice to that sense of isolation. Joy Division occupied prime spot. One of the most remarkable nights of my life was on the tour last year, when I asked New Order if they'd like to play New Dawn Fades with me. I had to teach Barney and Peter how to play it! Peter said that the last time they played it was when Ian Curtis was alive. If you'd told me when I was 16 that I'd fill Ian Curtis's shoes for four or five minutes, I'd never have believed you. If you go to a bar on the Lower East Side, you're bound to hear Joy Division. Nineties America was a dreadful time for music, it's not surprising bands like Interpol, The Killers or TV On The Radio, have skipped that decade. If you're 22 years old living in Williamsburg, who's going to be more inspiring, Limp Bizkit or Joy Division? The choice is pretty clear."

Interviews by Martin Aston and Danny Eccieston

=======================================================

THE DESIGNER

Peter Saville, creator of Joy Division and New Order's iconic cover art, talks to Martin O'Gorman about 25-plus years as their chief designer.

Despite glorious tales of rampant drug-taking during the making of Technique or frozen, flailing images of Ian Curtis, for the past 27 years the iconography of Joy Division and New Order has been defined by their records’ beautiful, elegant and monumental cover images, designed by Peter Saville. A graphic design student at Manchester Polytechnic, obsessed by Kraftwerk, Roxy Music and the modernist typography of Jan Tschichold, Saville’s first commercial project was the 1978 launch poster for The Factory club night run by then local TV journalist Tony Wilson. Inspired by the cover of Kraftwerk’s Autobahn, Saville based the Factory poster on an industrial warning sign he’d stolen from college. As the label’s co-founder and art director, Saville was given an unusual level of freedom to design whatever he wanted, free from budget constraints, free to indulge his artistic obsessions.

“There’s almost an interface image of New Order and Joy Division... a space occupied by imagery that I put into it,” explains Saville. “And people have a relationship with that abstract image — there’s almost a mythology about it.”

But now it seems we may finally be faced with a New Order cover that doesn’t have a direct involvement from Peter Saville. “What I wanted to do with the new New Order album [Waiting For The Sirens’ Call] was to reconstruct the cover for Power, Corruption And Lies, but with real flowers. I wanted to refabricate New Order in a way that’s relevant to their music now. But they were flabbergasted about that.”

So, leaving the art direction to his assistant, Howard Wakefield, and Bernard Sumner, it seems it’s time to move on. “I was honoured to create the interface for the music. But very few people would have taken to the package if it were not for the resonance of the music. We wouldn’t be talking about my Blue Monday if it were not for their Blue Monday...”

Unknown Pleasures (Factory, 1979)

Laid against a textured black sleeve is diagram 6.7 from Dr Simon Mitton's 1976 book. The Cambridge Encyclopaedia Of Astronomy, depicting 100 consecutive pulses from the first radio pulsar, discovered in 1919. The eerie image on the inner sleeve of a hand emerging from behind a door is taken from photographer Ralph Gibson's 1970 book. The Somnambulist.

Saville: "Somebody from the band gave me a file of material and said, 'We found this image, we'd quite like it on the front. We found this image, we'd quite like it on the inside. And we'd like it to be white on the outside and black on the inside.' I took these elements away and put it together to the best of my ability. No one said what size or where - I had to figure out how. I contradicted the band's instructions and made it black on the outside and white on the inside, which I felt had more presence. I had this idea of graining, because we had an expanse of flat black on the outside and texture would give it a more tactile quality. It was called Unknown Pleasures, so I thought the more this could be an enigmatic black thing, the more it might evoke the title."

Closer (Factory, 1980)

A hyper-realistic tombstone tableau from the Staglieno Cemetery in Genova, Italy forms the backdrop for Joy Division's swansong. The photos were taken in 1978 by Bernard Pierre Wolff and appeared in the September/October 1979 issue of French magazine Zoom. The tomb belongs to the Famiglia Appiani, incidentally.

Saville: "Joy Division were recording Closer and Rob [Gretton] decided they had to talk to me about the cover. I hadn't heard anything they'd recorded, so I said, I'll show you what I've seen recently that has thrilled me. Bernard Pierre Wolff had done a series of photographs in a cemetery in Italy. I don't know to this day whether they were real or not - some of them you thought, He's set that up. That's models, covered in dust. I thought the band would laugh, but they didn't. They were enthralled. They said, 'We' - that's 'we' - 'like that one.' The picture reminded me of 19th century engraving. So I used soft paper, the kind they'd use for engraving. I looked for a classical typeface and found the earliest example of serif lettering which I converted into a font. I was working in a pseudo-monumental way - as if I was doing a folly at Blenheim. Bad taste? I didn't know Ian personally, so it wasn't like one of my friends dying. Tony Wilson broke the news to me and I said, We have a problem - the album cover has a tomb on it. But the band said, 'We decided it together - Ian chose it.'The unsettling thing is wondering what was in his mind. I showed them photographs of a cemetery, while the quiet writer was penning the closest thing to a suicide note you can possibly get."

Movement

(Factory, 1981)

Eschewing the classical influences for the band's rebirth as New Order, FACT 50 features a reworking of a 1932 Futurist journal cover by Fortunato Depero. Note the "F" at the top of the design signifying "Factory", and the "L" at the bottom, signifying "50".

Saville: "Movement happened in exactly the same way as Closer. Rob brought them round and asked, 'What are you into?' I said, Italian Futurism. I showed them a book, they put post-it notes in it and left. They'd marked a particular poster, so I said OK, something like this? Rob said, 'No, not something like it. That.' We don't have time to mess around. I was compromised with Movement, so I wanted to put: 'Designed by Peter Saville, after Fortunato Depero'. [Then] Rob said, 'Those Futurists, they got mixed up with fascism, didn't they? We’ve had enough of that with Joy Division, take it off.' But the whole point was that it is a Futurist poster. They called the record Movement and Futurism as an art form was focused around speed and movement. In the early 20th century, the world was speeding up and it was a conjoined art and political movement."

Power, Corruption And Lies (Factory, 1983)

The themes of Blue Monday are carried over to the accompanying album, with Henri Fantin-Latour's 1890 painting A Basket Of Roses detourned with colour-coded symbols and no other text. The "code wheel" on the back cover is actually the letters of the alphabet and the numbers 0-9 rendered as colours - work out the code and you can work out the title.

Saville:"lt remains my personal favourite - Blue Monday and Power, Corruption And Lies are a collected work. Elements of Blue Monday are transferred onto the album and juxtaposed against the old painting. My own taste ranges from the factual to the romantic - the Dionysian and the Apollonian. The front and back of Power, Corruption And Lies are those two extremes. One is a florid, baroque oil painting of flowers, the other is a cool analysis of colours used to create the work. It's like the painting and the paint-tin. The wheel on the back is a composition of the colour-coded alphabet and an analysis of the colours in the painting with the process colours used to create the work. The colour alphabet came from the fact that I understood the floppy disk contained coded information and I wanted to impart the title in a coded form, to simulate binary code in a way - therefore I converted the alphabet into a code using colours."

Blue Monday

(Factory 12-inch single, 1983)

A 12-inch x 12-inch version of a floppy disk with die-cut holes and a silver inner sleeve accompanies the most successful 12-inch single ever and, from the brutalist electro-staccato drumbeats to Barney's unique new vocal stylings New Order's first real steps out of the shadow of Joy Division.

Saville: "I was in their rehearsal room discussing the artwork and picked upthis fascinating thing off the table. Steve [Morris] said, 'It's a floppy disk, haven't you ever seen one?' I asked him if I could have it and drove back to London listening to Blue Monday on a cassette but staring at this floppy disk. I knew that the sound I was hearing was being made by the sequencers and that the floppy disk carried the information, so there was an intrinsic link between the disk and their new direction. By the time I got to the end of the M1, I knew the cover of Blue Monday would be a floppy disk. Was it expensive? For a single, it was expensive, but all the rumour around it is, in my opinion, nonsense. Tony Wilson is a great exponent of"print the myth".Twelve-inch singles don't have the profit margins that albums have... but this was Factory, who the fuck cared? I thought somebody would adjust the price to compensate. But I don't think that anybody knew the price of the Blue Monday sleeve until they got the bill."

Low-Life (Factory, 1985)

New Order get upfront for the first time - the cover bears a Polaroid photo of drummer Stephen Morris by Trevor Key, with Gillian Gilbert on the back. The entire package is covered with heavy tracing paper that bears the name of the band and the title.

"Somebody described Low-Life and said that the tracing paper around the sleeve was like the veil of secrecy around New Order. And I thought, Really? But then when I thought about it, I found that's a very beautiful way of putting what I subconsciously already knew. I knew that if I put heavy tracing paper over the images which obscured them to some extent, it did put something between you and the person. That's why I thought it was groovy."

Get Ready (London, 2001)

Young model brandishes video camera in grainy shot by noted photographer Jurgen Teller for the "comeback" album. Savillesque graphics intrude. No titles on cover.

Saville: "For Get Ready, I went through the usual process. I showed them some material that was interesting to me, then Bernard told me what he wanted. What I was showing him didn't connect, but he saw something else that did. It was a young person with a movie camera, looking at the camera. And I saw a kind of metaphor in that, which was 'Don't look here, look at yourself. So I passed that image on to photographer Jurgen Teller. I was 46 years of age when that record came out and the things that interest me do not belong on a CD cover. I found things that were pertinent to the world of marketing and the commodification of our pop culture but those things did not resonate with Bernard. So we had to disagree on this one."

Retro (London, 2002)

Big scary teutonic eagle sizes up to smashed disco ball for the New Order box set. Get the message? Barney did.

Saville: "Bernard was going away, so I told him about it on the phone, but he didn't really take much notice. He came back and saw it and said, 'Peter, What's this about?' I said, What do you think it's about? He said, 'I think it's about the past.' And I said, You're dead fucking right! The eagle's Joy Division, the broken disco ball's New Order. He said, 'But don't we get a lot of grief about the past?' I said, Come on Bernard, it's 20 years ago, get over it! It was inspired by something I saw in Helmut Lang's shop in New York, which was an assemblage of disco balls and a huge carved wooden eagle. I'm telling an allegorical story there. It's like the last days of disco and a teutonic eagle. Now that means something to me."

=======================================================

THE SURVIVORS

Following the death of Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis, New Order struggled through 25 years of debt, drugs, booze and dissolution in a quest for blissful music. Now they're back, they tell Ann Scanlon.

WHEN BERNARD SUMNER IS ASKED TO pick a definitive moment in New Order’s 25-year-long history, he doesn’t give the question a second’s thought. His mind flashes back to the day in 1998 when he sat down alongside bassist Peter Hook, drummer Stephen Morris and keyboard player Gillian Gilbert in manager Rob Gretton’s office in Whitworth Street, Manchester, and decided to give New Order another go, a whole five years after they had last walked off-stage together and seemingly turned their backs on each other for good.

“You see,” he says, “the great thing about the years we were apart was that we never thought we’d play together again. And having that thought in our minds for five years purged all the animosity between us. So the feeling of camaraderie in that office that day was the same kind of feeling that we had for each other in the Joy Division days. It was like something special had been given back to us.”

In the seven years since, New Order have suffered the death of Gretton, the man who managed them for 22 years, and the loss of Gilbert, who quit the band in 2001 to look after her and Morris’s youngest daughter who was seriously ill at the time.

If the story of New Order is about anything it’s about survival.

Not many bands would have overcome the death of their lead singer, much less one as startlingly individual as Ian Curtis, but New Order managed to rise from the ashes of Joy Division to become one of the most significant British bands of our time and the cornerstone of Manchester’s Factory Records empire and the Haqienda nightclub. And then, just when they seemed to be on the verge of mega-stardom, they watched everything collapse, enduring financial despair, alcohol and drug burn-out, and finally that acrimonious split. But through it all remained an inextinguishable, inescapable lust for life. This is obvious when MOJO first meets New Order on the last Wednesday evening in November 2004 at a playback session for their new album at Olympic Studios in Barnes, south-west London.

A handful of people from the band’s press and management companies, plus Sumner, Morris and Phil Cunningham — the ex-Marion guitarist/keyboard player who replaced Gilbert — are gathered in a candle-lit studio to hear nine out of the 18 tracks recorded for the new album, Waiting For The Sirens’ Call. On first listen, it sounds like classic New Order: big, uplifting tunes, tinged with their trademark beautiful melancholy. After the playback, Sumner politely answers questions and seems genuinely interested in everyone’s opinion. A couple of hours later, though, he seems to have a different kind of sirens’ call on his mind. “Who’s coming to the Groucho Club?” he asks by way of a general invitation. “We’ve been living like monks for the past month and tonight we’re going to have a seriously good time.”

Which is possibly why — after spending the evening with a posse that includes New Order associates Keith Allen and Arthur Baker, as well as Damien Hirst and Shane MacGowan — he is still in the Soho club at 3am, being subjected to a loud rendition of Temptation from a complete stranger in the men’s toilets and only finally flees back to Barnes in order to avoid the further offer of a late-night visit to a Japanese karaoke bar.

As someone who started to suffer from insomnia after Joy Division recorded Unknown Pleasures, Sumner is all too aware of the lure of the night. This is a man who toured his way through the 1980s, ingesting whatever amount of booze and drugs that came his way. “After the concert we’d all be pretty high and we’d have a party back at the hotel,” he says. “We just got into partying every night: doing drugs and drinking huge amounts.”

This belies one of the biggest misconceptions about Joy Division/New Order: that the people in the band are as serious and intense as their music. “I suppose our humour was a big contrast to the music,” admits Sumner when we meet again at a country hotel near Macclesfield in mid-December. “The only period when we weren’t a laugh was when we were doing too many drugs.”

Even so it must have taken a hell of a sense of humour to get through the early days of New Order. As stunned and depressed as the band were by the loss of their close friend and frontman, they knew they had to go on. “Ian died in May 1980 and we didn’t exactly have a long period of mourning,” says Stephen Morris. “Everything was decided at the so-called wake at the Factory office on the Palatine Road. Tony made us watch The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle, and it was, ‘So what are we doing then?’ ‘Rehearsal next Wednesday?’ ‘Right, see you then.’”

At the end of July, Morris, Sumner and Flook made their New Order debut, as a trio sharing vocal duties, at a Manchester club called the Beach. That September, they went to the US to play a handful of live shows on the East Coast and to record a version of their first single, Ceremony, with Martin Hannett. Sumner recalls a particularly memorable morning in the Iroquois Hotel in New York, which turned out to be a portent of financial disasters to come.

“I remember being woken up by Tony Wilson, who was shaking me and laughing his head off. He said, ‘You’ll never guess what’s happened. All the gear’s been stolen.’ He thought it was extremely funny, although to be fair to him he didn’t know that we weren’t insured.’”

Fortunately, they could see the funny side. Until they got hit with a tax bill for the 300,000-plus US sales of Joy Division’s first two albums and found out that Rough Trade America had gone bust without giving the band any money.

“So Ian died, we went to America, got the gear stolen, came back and then got called into Manchester to see the tax officers,” says Sumner. “There was a big burly Scotsman with a Glaswegian accent, and he was Mr Nasty, and then we had Mr Nice, who was a little weedy bloke. We kept being called in for meetings and it got to the point where we all had to make an inventory of everything in our houses, so the bailiffs could come round. It felt like fate was stacked up against us and whatever we did something went horribly wrong. ”

By this time Rob Gretton had persuaded the band to buy a nightclub as a joint venture between New Order and Factory Records. The Hacienda, on Manchester’s Whitworth Street, opened on May 21, 1982, and the new business gave a smart London lawyer the leeway to substantially reduce the band’s outstanding tax bill, allowing them to move forward once again.

In the meantime, New Order had been searching for an electronic sound that was utterly their own and, in October 1982, they recorded Blue Monday. This was the turning point. Initially released in March 1983, it sold throughout the summer, reaching the Top 10 in October, and becoming the biggest selling 12-inch single of all time. However, due to its elaborate packaging, both Factory and New Order reputedly lost money every time somebody bought a copy (estimates of the loss range from £1 to 50p to a more manageable 2.7p).

The pattern continued over the next four years as New Order continued to make a series of best-selling records, but used much of the profits to support their struggling nightclub. Then suddenly; in 1987/88, everything came together when the Hacienda — and Manchester — entered its glory period.

“That was a good time,” recalls Morris. “It was the Summer of Love and we made the most of it. First G-Mex, then touring America, recording in Ibiza, the off-the-faceness continued throughout those years.” Trying to make an album in Ibiza with everyone on Ecstasy was a disaster. Tony Wilson later described Technique as “the most expensive holiday [New Order] have ever had”, but the album (the majority of which was finished in Bath) went straight to Number 1 in February 1989. Then things really started to go wrong.

“We had all been lulled into a false sense of security by the whole Summer of Love/acid house malarkey,” says Morris. “The Hacienda’s rammed, we’ve got the Dry bar (Factory’s designer bar, opened on Manchester’s Oldham Street in May 1989), Tony’s got the Happy Mondays, everyone’s having a good time, we’re onto a winner — great! And then the E wore off.”

In July 1989, 16-year-old Claire Leighton collapsed in the Hacienda after taking an Ecstasy pill and became the drug’s first fatality. Before long, the Hagienda had become a hang-out for rival gangs of drug dealers, who brought violence, guns and fear into the club. Not surprisingly, the crowds kept away.

“For five or six years the Hacienda was a wonderful place to go,” says Hook. “In 1987 we won an award for the most courteous doormen, that was when they used to wear Crombies and were all dead smart. The place literally had no trouble until the acid explosion and then things got very heavy. It got to the point where you feared for your safety every time the phone rang in the middle of the night. It wasn’t just a case of one of your family being ill, it was whether someone had got killed in the Hacienda. The only good thing about it was that you were so off your head on drugs you didn’t realise the true gravity of it at the time.”

Throughout 1990, the police kept a close watch on the Hacienda and in January 1991 Tony Wilson announced that it was closing voluntarily after door staff had been threatened with a gun. It reopened on May 10 with new security measures, but by this time Factory was on the brink of financial collapse. The bottom had fallen out of the property market and the company discovered that three of the buildings they’d bought and renovated at enormous expense were now worth nowhere near the amount they’d spent on them. In the space of three months the value of the Hacienda crashed from £lm to just £300,000. Factory had no choice but to pressure their two biggest acts, New Order and Happy Mondays, to get their new albums out.

Happy Mondays were sent to record Yes Please in Barbados, a venture that descended into a month of madness — crack cocaine, broken limbs, a string of crashed cars — that ended with Shaun Ryder’s decision to hold the stolen master tapes to ransom while demanding more money from Factory to buy drugs. The recording of New Order’s new album proved to be significantly less fun than that.

“Republic was very difficult because we hated each others’ guts,” says Hook. “We were also having crisis life-saving meetings, trying to stave off the bankrupt Hagienda and the bankrupt Factory from the liquidators. It was ridiculous.”

Morris: “Recording Republic was like having a gun put to your head. Trying to write an album but being aware that the fate of the record company is resting on you doing it was a lot of pressure. Gillian came up with the bold idea that we should go on strike. And she was absolutely right. But to our regret, we didn’t.”

Sumner: “By that time the record company was burnt out and I personally felt really burnt out. We’d been boxed together for quite a few years, like sardines, plus all the drinking and drugs that we’d been doing had just messed us up. I think if at that stage somebody had said to us, ‘Let’s just stop for two years and sort out our business problems’, we wouldn’t have fallen out with each other. But there were too many invested interests and a lot of egos at stake.”

In November 1992, Factory went into receivership; Republic was released on London Records the following May. But that didn’t improve relations in the New Order camp.

At the end of their US tour in July 1993, Sumner told Hook, “If I never see your face again, it’ll be too soon.”

Unfortunately, he was forced to see him again at the band’s final date at Reading Festival on August 29.

“That whole American tour was hell,” remembers Morris. “Bernard got ill, we were getting on even worse than ever and then we came back, walked off-stage at Reading and that was it. Nobody said, ‘See vou next week’ or ‘next month’. Nobody said anything. We just went home.”

For Sumner, the end was a massive relief. “New Order had strayed away from its roots,” he says. “We’d diversified into things we shouldn’t have. It made me angry and that kind of anger burns you up and makes you nasty. But I don’t want people to get the wrong idea about Factory, because it was a great thing. It allowed us to express ourselves and to develop. You know, if we hadn’t had to struggle so much we might never have made the music that we did. ”