2008 05 10 Jon Savage on "Joy Division", The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/may/10/popandrock.joydivision

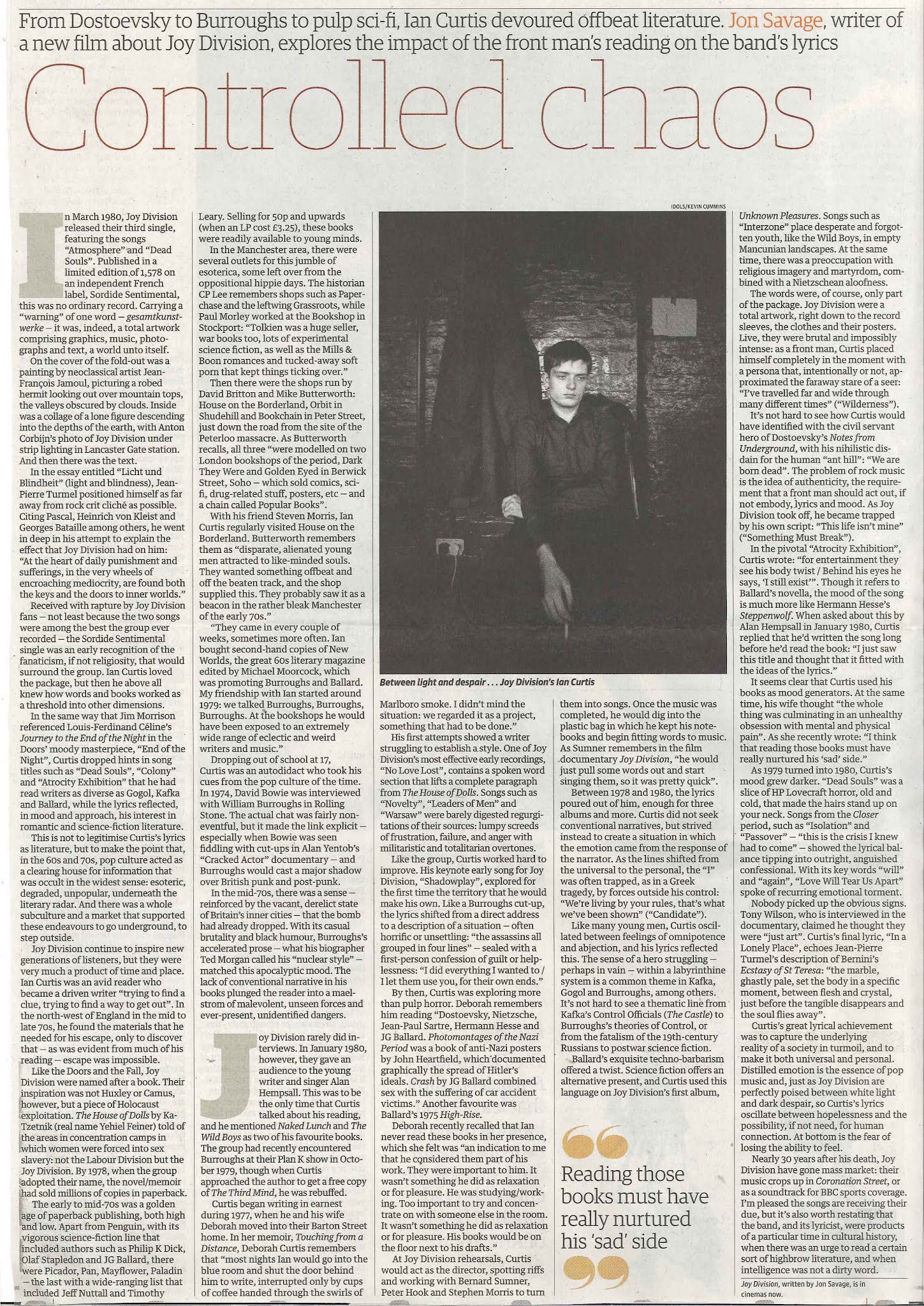

From Dostoevsky to Burroughs to pulp sci-fi, Ian Curtis devoured offbeat literature. Jon Savage, writer of a new film about Joy Division, explores the impact of the front man's reading on the band's lyrics

Controlled chaos

On the cover of the fold-out was a painting by neoclassical artist Jean-Francois Jamoul, picturing a robed hermit looking out over mountain tops, the valleys obscured by clouds. Inside was a collage of a lone figure descending into the depths of the earth, with Anton Corbijn's photo of Joy Division under strip lighting in Lancaster Gate station. And then there was the text.

In the essay entitled "Licht und Blindheit" (light and blindness), Jean-Pierre Turmel positioned himself as far away from rock crit cliché as possible. Citing Pascal, Heinrich von Kleist and Georges Bataille among others, he went in deep in his attempt to explain the effect that Joy Division had on him: "At the heart of daily punishment and sufferings, in the very wheels of encroaching mediocrity, are found both the keys and the doors to inner worlds."

Received with rapture by Joy Division fans - not least because the two songs were among the best the group ever recorded - the Sordide Sentimental single was an early recognition of the fanaticism, if not religiosity, that would surround the group. Ian Curtis loved the package, but then he above all knew how words and books worked as a threshold into other dimensions.

In the same way that Jim Morrison referenced Louis-Ferdinand Céline's Journey to the End of the Night in the Doors' moody masterpiece, "End of the Night", Curtis dropped hints in song titles such as "Dead Souls", "Colony" and "Atrocity Exhibition" that he had read writers as diverse as Gogol, Kafka and Ballard, while the lyrics reflected, in mood and approach, his interest in romantic and science-fiction literature.

This is not to legitimise Curtis's lyrics as literature, but to make the point that, in the 60s and 70s, pop culture acted as a clearing house for information that was occult in the widest sense: esoteric, degraded, unpopular, underneath the literary radar. And there was a whole subculture and a market that supported these endeavours to go underground, to step outside.

Joy Division continue to inspire new generations of listeners, but they were very much a product of time and place. Ian Curtis was an avid reader who became a driven writer "trying to find a clue, trying to find a way to get out". In the north-west of England in the mid to late 70s, he found the materials that he needed for his escape, only to discover that - as was evident from much of his reading - escape was impossible.

Like the Doors and the Fall, Joy Division were named after a book. Their inspiration was not Huxley or Camus, however, but a piece of Holocaust exploitation. The House of Dolls by Ka-Tzetnik (real name Yehiel Feiner) told of the areas in concentration camps in which women were forced into sex slavery: not the Labour Division but the Joy Division. By 1978, when the group adopted their name, the novel/memoir had sold millions of copies in paperback.

The early to mid-70s was a golden age of paperback publishing, both high and low. Apart from Penguin, with its vigorous science-fiction line that included authors such as Philip K Dick, Olaf Stapledon and JG Ballard, there were Picador, Pan, Mayflower, Paladin - the last with a wide-ranging list that included Jeff Nuttall and Timothy Leary. Selling for 50p and upwards (when an LP cost £3.25), these books were readily available to young minds.

In the Manchester area, there were several outlets for this jumble of esoterica, some left over from the oppositional hippie days. The historian CP Lee remembers shops such as Paper-chase and the leftwing Grassroots, while Paul Morley worked at the Bookshop in Stockport: "Tolkien was a huge seller, war books too, lots of experimental science fiction, as well as the Mills & Boon romances and tucked-away soft porn that kept things ticking over."

Then there were the shops run by David Britton and Mike Butterworth: House on the Borderland, Orbit in Shudehill and Bookchain in Peter Street, just down the road from the site of the Peterloo massacre. As Butterworth recalls, all three "were modelled on two London bookshops of the period, Dark They Were and Golden Eyed in Berwick Street, Soho - which sold comics, sci-fi, drug-related stuff, posters, etc - and a chain called Popular Books".

With his friend Steven Morris, Ian Curtis regularly visited House on the Borderland. Butterworth remembers them as "disparate, alienated young men attracted to like-minded souls. They wanted something offbeat and off the beaten track, and the shop supplied this. They probably saw it as a beacon in the rather bleak Manchester of the early 70s."

"They came in every couple of weeks, sometimes more often. Ian bought second-hand copies of New Worlds, the great 60s literary magazine edited by Michael Moorcock, which was promoting Burroughs and Ballard. My friendship with Ian started around 1979: we talked Burroughs, Burroughs, Burroughs. At the bookshops he would have been exposed to an extremely wide range of eclectic and weird writers and music."

Dropping out of school at 17, Curtis was an autodidact who took his cues from the pop culture of the time. In 1974, David Bowie was interviewed with William Burroughs in Rolling Stone. The actual chat was fairly non-eventful, but it made the link explicit - especially when Bowie was seen fiddling with cut-ups in Alan Yentob's "Cracked Actor" documentary - and Burroughs would cast a major shadow over British punk and post-punk.

In the mid-70s, there was a sense - reinforced by the vacant, derelict state of Britain's inner cities - that the bomb had already dropped. With its casual brutality and black humour, Burroughs's accelerated prose - what his biographer Ted Morgan called his "nuclear style" - matched this apocalyptic mood. The lack of conventional narrative in his books plunged the reader into a maelstrom of malevolent, unseen forces and ever-present, unidentified dangers.

Joy Division rarely did interviews. In January 1980, however, they gave an audience to the young writer and singer Alan Hempsall. This was to be the only time that Curtis talked about his reading, and he mentioned Naked Lunch and The Wild Boys as two of his favourite books. The group had recently encountered Burroughs at their Plan K show in October 1979, though when Curtis approached the author to get a free copy of The Third Mind, he was rebuffed.

Curtis began writing in earnest during 1977, when he and his wife Deborah moved into their Barton Street home. In her memoir, Touching from a Distance, Deborah Curtis remembers that "most nights Ian would go into the blue room and shut the door behind him to write, interrupted only by cups of coffee handed through the swirls of Marlboro smoke. I didn't mind the situation: we regarded it as a project, something that had to be done."

His first attempts showed a writer struggling to establish a style. One of Joy Division's most effective early recordings, "No Love Lost", contains a spoken word section that lifts a complete paragraph from The House of Dolls. Songs such as "Novelty", "Leaders of Men" and "Warsaw" were barely digested regurgitations of their sources: lumpy screeds of frustration, failure, and anger with militaristic and totalitarian overtones.

Like the group, Curtis worked hard to improve. His keynote early song for Joy Division, "Shadowplay", explored for the first time the territory that he would make his own. Like a Burroughs cut-up, the lyrics shifted from a direct address to a description of a situation - often horrific or unsettling: "the assassins all grouped in four lines" - sealed with a first-person confession of guilt or helplessness: "I did everything I wanted to / I let them use you, for their own ends."

By then, Curtis was exploring more than pulp horror. Deborah remembers him reading "Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre, Hermann Hesse and JG Ballard. Photomontages of the Nazi Period was a book of anti-Nazi posters by John Heartfield, which documented graphically the spread of Hitler's ideals. Crash by JG Ballard combined sex with the suffering of car accident victims." Another favourite was Ballard's 1975 High-Rise.

Deborah recently recalled that Ian never read these books in her presence, which she felt was "an indication to me that he considered them part of his work. They were important to him. It wasn't something he did as relaxation or for pleasure. He was studying/working. Too important to try and concentrate on with someone else in the room. It wasn't something he did as relaxation or for pleasure. His books would be on the floor next to his drafts."

At Joy Division rehearsals, Curtis would act as the director, spotting riffs and working with Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook and Stephen Morris to turn them into songs. Once the music was completed, he would dig into the plastic bag in which he kept his notebooks and begin fitting words to music. As Sumner remembers in the film documentary Joy Division, "he would just pull some words out and start singing them, so it was pretty quick".

Between 1978 and 1980, the lyrics poured out of him, enough for three albums and more. Curtis did not seek conventional narratives, but strived instead to create a situation in which the emotion came from the response of the narrator. As the lines shifted from the universal to the personal, the "I" was often trapped, as in a Greek tragedy, by forces outside his control: "We're living by your rules, that's what we've been shown" ("Candidate").

Like many young men, Curtis oscillated between feelings of omnipotence and abjection, and his lyrics reflected this. The sense of a hero struggling - perhaps in vain - within a labyrinthine system is a common theme in Kafka, Gogol and Burroughs, among others. It's not hard to see a thematic line from Kafka's Control Officials (The Castle) to Burroughs's theories of Control, or from the fatalism of the 19th-century Russians to postwar science fiction.

Ballard's exquisite techno-barbarism offered a twist. Science fiction offers an alternative present, and Curtis used this language on Joy Division's first album, Unknown Pleasures. Songs such as "Interzone" place desperate and forgotten youth, like the Wild Boys, in empty Mancunian landscapes. At the same time, there was a preoccupation with religious imagery and martyrdom, combined with a Nietzschean aloofness.

The words were, of course, only part of the package. Joy Division were a total artwork, right down to the record sleeves, the clothes and their posters. Live, they were brutal and impossibly intense: as a front man, Curtis placed himself completely in the moment with a persona that, intentionally or not, approximated the faraway stare of a seer: "I've travelled far and wide through many different times" ("Wilderness").

It's not hard to see how Curtis would have identified with the civil servant hero of Dostoevsky's Notes from Underground, with his nihilistic disdain for the human "ant hill": "We are born dead". The problem of rock music is the idea of authenticity, the requirement that a front man should act out, if not embody, lyrics and mood. As Joy Division took off, he became trapped by his own script: "This life isn't mine" ("Something Must Break").

In the pivotal "Atrocity Exhibition", Curtis wrote: "for entertainment they see his body twist / Behind his eyes he says, 'I still exist'". Though it refers to Ballard's novella, the mood of the song is much more like Hermann Hesse's Steppenwolf. When asked about this by Alan Hempsall in January 1980, Curtis replied that he'd written the song long before he'd read the book: "I just saw this title and thought that it fitted with the ideas of the lyrics."

It seems clear that Curtis used his books as mood generators. At the same time, his wife thought "the whole thing was culminating in an unhealthy obsession with mental and physical pain". As she recently wrote: "I think that reading those books must have really nurtured his 'sad' side."As 1979 turned into 1980, Curtis's mood grew darker. "Dead Souls" was a slice of HP Lovecraft horror, old and cold, that made the hairs stand up on your neck. Songs from the Closer period, such as "Isolation" and "Passover" - "this is the crisis I knew had to come" - showed the lyrical balance tipping into outright, anguished confessional. With its key words "will" and "again", "Love Will Tear Us Apart" spoke of recurring emotional torment.

Nobody picked up the obvious signs. Tony Wilson, who is interviewed in the documentary, claimed he thought they were "just art". Curtis's final lyric, "In a Lonely Place", echoes Jean-Pierre Turmel's description of Bernini's Ecstasy of St Teresa: "the marble, ghastly pale, set the body in a specific moment, between flesh and crystal, just before the tangible disappears and the soul flies away".

Curtis's great lyrical achievement was to capture the underlying reality of a society in turmoil, and to make it both universal and personal. Distilled emotion is the essence of pop music and, just as Joy Division are perfectly poised between white light and dark despair, so Curtis's lyrics oscillate between hopelessness and the possibility, if not need, for human connection. At bottom is the fear of losing the ability to feel.

Nearly 30 years after his death, Joy Division have gone mass market: their music crops up in Coronation Street, or as a soundtrack for BBC sports coverage. I'm pleased the songs are receiving their due, but it's also worth restating that the band, and its lyricist, were products of a particular time in cultural history, when there was an urge to read a certain sort of highbrow literature, and when intelligence was not a dirty word.

· Joy Division, written by Jon Savage, is in cinemas now

Comments

Post a Comment