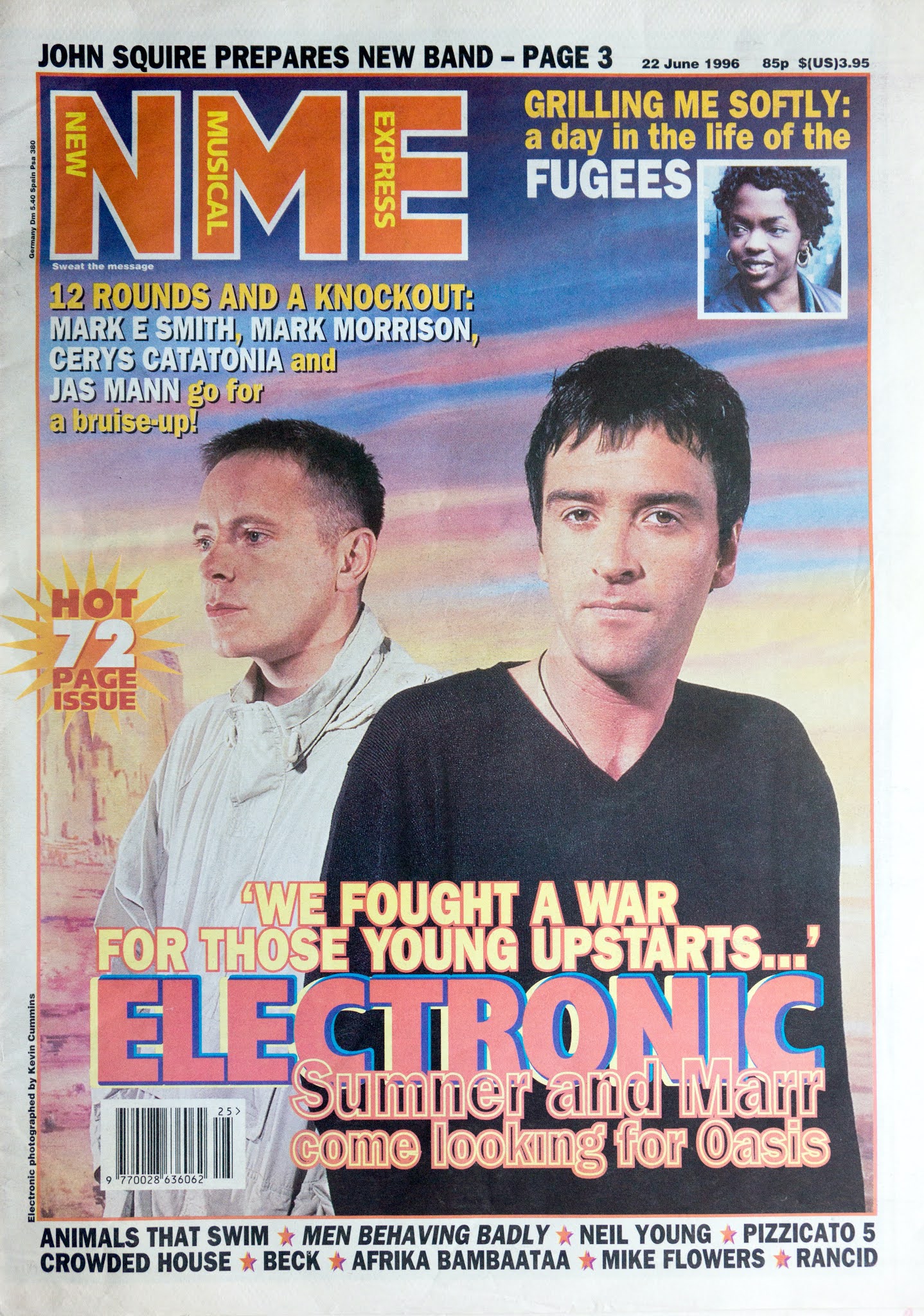

1996 06 22 Electronic NME

JOGGERS PLAY POP

• Any band that hangs out with George Michael, forsakes drugs for jogging and spends five years on that difficult second album must be completely arse, right? Wrong. Not when they're ELECTRONIC, aka Johnny ‘Smiths’ Marr and Bernard ‘New Order' Sumner. TED KESSLER finds out what took them so long. Getting away with it KEVIN CUMMINS

Well, you know what happens when you go on the piss with the Pet Shop Boys. You start off in the studio with a couple of kir royales and every intention of getting back to the hotel in time for cooked room service. But by the time you’ve finished playing Neil the album you’ve jettisoned the kir and started swigging the champagne straight from the bottle. So when Neil announces he’s off to Heaven, it seems churlish not to join him.

Heaven, it seems, is stiil a good place. Unlike most London dubs it’s not exclusively populated by either snotty-nosed ravers or fashion nazis, and tonight it really feels like these are the good times again. But despite this egalitarian atmosphere, Johnny Mari', Bernard Sumner and Neil Tennant aren't the only big-deal stars in tonight. George Michael is swigging mineral water by the bar.

Neil goes over to greet George, and introduces him to Johnny and Bernard. “F—ing hell,” thinks Johnny, "that’s George Michael! Isn't he, like, a bit difficult?” Johnny's not nervous as such but... well, yes he is actually.

George Michael, however, turns out to be a lovely man. He's charming, he’s funny, and he’s coming back to Johnny and Bernard’s studio to hear a mix of the hew Electronic album. Turns out he's a fan.

Once back at the studio, fresh supplies of champagne and wine are corked and the new Electronic album is slipped on to the deck. As the first verse of the first single, ‘Forbidden City’, gushes from the speakers Johnny and Bernard exchange worried glances. One of the backing vocal trades is missing! It still sounds ace and only they could possibly notice the error, but they make mental notes to correct it in the morning. The song fades to a dose. They both turn to George and quizzically raise their eyebrows. George returns their gaze with a smile.

“It’s a very good song,” he says evenly, "but I really think you need another backing vocal track on the first verse. Can I hear the rest of the album?”

What a guy! Not only does he like the song, but he’s honest and open enough to point out a fault! It’d be a pleasure to play you the whole thing, mate.

They're all pleasantly caned by the time the record pulls into the station an hour later, and George has a warm grin slashed across his face.

"That was excellent," he laughs. "Do you think we could hear it again?" Johnny winks at Bernard and flips the tape over. George, for you, anything. If only you could put moments like these in a box and take them home for times when your pride's been dented. George Michael rules! Yeah, and so do Electronic! Alright!

By the time the album finishes for the second time. George is silently rocking in his char. He doesn't talk when he's listening to music, he just soaks it all up. He really listens. Johnny and Bernard are by now in healthy awe of the guy. Still, it's late and George has got to be going. Ah, well. They all exchange embraces. They are comrades.

“Did you not love his voice, Bernard?" giggles Johnny, as George glides down the corridor. "It’s so soft. Like a baby angel! It's like having your ears massaged with little pillows! God, I wanted to say that if anyone wants to speak to me, could they not tell George first and get him to do all that talking! It was that nice!"

They’re both bent double in convulsions of laughter, but suddenly Johnny grabs Bernard’s arm.

"You know what we've just done,” he says, deadly serious. “We’ve just played George Michael our album twice, right.. . but we never once asked him how his new record’s coming along! What a pair of ignorant bastards!"

Johnny Marr stretches his face and bares his teeth in embarrassment. Bernard Sumner puts his bands up to his cheeks and forces his lips into an O. They hold this pose for about five seconds. And then they both start laughing so hard that they nearly fall over.

A WEEK later, Bernard Sumner is sitting in the lobby of a swanky Mancunian hotel sipping tea, waiting for Johnny Marr and a plate of chicken sandwiches to turn up. He’s early, but they’re both late.

He caught the bus down. Hasn’t taken public transport for a while, but he just fancied it. And you know what, it was alright on the bus. Couple of quid and, bang, you're in town. Easy.

And so here he is, back on the old treadmill. It’s been, what, five years since the first and last Electronic album, a good three since the last New Order tour and Number One album, ‘Republic', and two since he and Johnny started writing and recording the new Electronic album, ‘Raise The Pressure', which is due out on July 8, in Johnny’s studio. What’s it going to be like now he’s blotted out the numb memories of promoting past glories? Will it feel like starting a new job that you quit years ago?

Who knows? He can remember what it’s like to haul his arse around the globe promoting a record, but can he remember what it feels like? Anyway, things are different now. He’s different.

It's nearly 20 years since he started his illustrious hike through music, and his two previous groups, Joy Division and New Order, both made important, indelible marks on the face of music, for sure. But everything about Electronic is different from those groups (apart from the signature of the music, of course, which still breathes with the same beautifully doomed fatalism).

For a start, this is not a democracy - it’s a shared dictatorship. Bernard doesn't have to worry about three other egos pulling in different directions, and Johnny Marr doesn't have to worry about hearing himself play guitar over the drummer’s hi-hat in the soundcheck. Like a pair of relaxed newlyweds, they just have each other.

Fans routinely ask Bernard and Johnny how they could turn their backs on their former groups (for the very young: Johnny Marr was the tunesmith in arguably the most feted and influential band of the 80's, The Smiths, and he directly shaped the likes of Noel Gallagher and Bernard Butler. He used his guitar simply as a tool with which to carve wonderful songs, rather than an extension of his willy. As such, he's something of a rarity in the guitar community). But really there’s no comparison.

Now, for instance, instead of laboriously writing and recording an album as a four-piece group and compromising their ideas a tad in the process, before touring around the world for months on end with a bunch of people you aren’t sure you like that much anymore, they simply tell their engineer they’ll see him at ten tomorrow morning. They do all their work together because they like each other’s company and respect one another’s methods. Which is an improvement already.

When they eventually turn up some time after lunch they all have a chat and a cup of tea, do some technical stuff, and slowly work themselves up to The Moment. None of us would be aware, of course, of when The Moment is nigh, but when you’ve been making records as long and as well as Johnny Marr and Bernard Sumner, you know. That’s when they do their good stuff, in those few golden hours some time around sunset That’s when they actually create their deceptively brilliant music.

Deceptive because the first time you hear ‘Raise The Pressure’, say, at home on a gloomy, rainy afternoon, it just sounds like a piece of well-produced fluff. But give It a week and give it some sun. That’s when these majestic songs really sprout and then you’ll be stuck with them because, ah, catchy's not a very pretty description, is it? But that's what they are. It sounds unusual in these times, too, because although Sumner and Marr are both accomplished musicians it doesn't attempt to trawl down any well-worn rock paths towards an 'authentic’ sound. It's not made for other musicians or studio engineers or late-night gauging out. The song is everything. And the songs are very good.

It's an album for footloose mums and dads who still live for Saturday night clubbing, but who also spend too much time staring out from windows alone. An album that knows its girlfriend is a little too young. The sad guitar songs are probably better than the European house ones but that’s Electronic’s little quirk (encouraged no doubt by Karl Bartos of Kraftwerk, who helped write some of the tracks). There are also at least five cracking singles aboard, and two - 'Forbidden City' and 'For You' - have already been earmarked as such. So, really, it’s a result for Sumner and Marr. By the way, where is Johnny?

“HE’LL BE here soon,” says Bernard tucking into his sandwich. Bernard, mild, engaging and softly-spoken, has a sharpened sense of humour, and when he and Marr get together they’re world-class gossips. But he’s formidable on his own too, especially when former bass foil Peter Hook’s recent tabloid-sponsored split from wife Caroline (aka Mrs Merton) is mentioned.

"Well, what’s he done now?” he asks, a glint in his eye. “It must be bad because she’s kicked him out, hasn’t she? I don’t know, I haven’t seen him. At least that’ll put an end to the 12"-dick stories. I remember on tour with New Order Hooky used to walk around with this tiny dressing gown on and, well, we’re talking 12cms, not inches.”

Suddenly, Johnny Marr, looking slim and tanned, bounds up the steps to the tea room. Bernard, who has no real interest in football, immediately starts ribbing ardent Man City fan Marr about City’s recent relegation. Johnny pulls the face of a man who’s heard nothing else for weeks. When bored with this tack Bernard reminds Johnny and their record company representative about a bull terrier that terrorised them at a recent photo shoot.

“I’d love one of those dogs, you know. You could really intimidate people when they came round your house, because as soon as you walk in they just ram their noses right into your crotch. Which would be good for me too, having something ram its nose into my testicles as soon as I walk in. My absolutely massive testicles, I might add.

“Right,” he says, grabbing his bollocks, “should we go up to the room and do the interview now?’"

THERE ARE two fluffy white bathrobes laid out on the bed in the room, but sadly neither Marr nor Sumner wish to don them for the interview. Johnny will keep his cool black Joseph top on, ta, and Sumner feels similarly about his paste) number. Both dress with a casual elegance that comes from wealth and taste, and that no doubt enrages teenage scally ticket touts with jealousy.

Luckily for NME’s lawyers, a lot of the duo’s natural loose-tongued prattle gets packed away for interviews, and it’s replaced by an eloquent matter-of-factness. They're professionals. They'll tell you

what you want to know, whether it be about Morrissey or the sexual advantages of Prozac, but they can't afford to lose any sleep over what they impart. One of the most revealing quotes, in fact, comes at the very end of the interview when Johnny’s asked whether there’s anything else he'd like to say.

“I tell you what,” he replies. “Morrissey was the best journalist who never was. Better than most actually. So he had a very definite idea of what would make a good quote and what wouldn't. He had it all sorted in his head. So I was very wary of saying what I wanted in interviews in The Smiths. I couldn’t talk about football or whatever I was into. Now I say what I like and I won't talk about anything I don't want to. It's a lot easier that way."

The boundaries are pretty clear, then. They have, nevertheless, been away a long time. There's plenty to discuss. Like, what took so long?

"I think we were conscious of not repeating ourselves," muses Bernard. "We'd write a song and go, 'Mmm, we've done that sort of thing before'. In the end we got analytical and had to retract our heads from our anuses.”

"W« rejected so many ideas, " adds Johnny. "We had a kind of agenda at the start which was... I can't remember now! We didn’t want to make a record that would sound good to other musicians in studios or at half two in the morning. We wanted to keep it interesting for the public without appearing too laid-back.”

Bernard: “We wanted to use methods that we hadn’t used before, but if you do that you strip away all your experience and that can be detrimental. Once we stopped thinking about it too hard it was alright. It’s a good album."

Things have changed a fair amount since you last ventured out of Johnny’s studio. Oasis have bloodied grunge and Britpop rules the waves. How do you think Oasis would’ve fared when The Smiths and New Order were still active?

Johnny: “It was the dark ages in terms of getting radio play in the ’80s on Radio 1. Certain reactionaries at the station would take umbrage at the lyrics, others wouldn’t like the style or the sound effects we used at the start of a track or thought The Smiths were too radical. So we didn’t get the airplay even though we were really popular, and we did a lot of tin-opening for Oasis in terms of getting airplay. But Oasis will open doors for other groups. They deserve their success.”

Bernard: “I’m surprised by how traditional Britpop is, though. It’s quite safe.”

Johnny: “Sure, that’s why it goes right across the board. Young people get into Oasis because they haven’t heard it before, while older people who haven’t bought a decent record for years will also get into it. You can’t get elitist about it. There’s a trick to it. Lots of bands have tried it, U2 for example, but to appeal to people with taste and people who are street, and have that respect while playing stadiums takes some doing.”

Bernard: “It’s weird for me because I’m used to people hating their parents’ record collections. Now they embrace them. Same with fashion. The ’70s are in, the ’60s are in. At the end of each millennium we regurgitate that millennium and that’s what we’re seeing now. In the '80s, Oasis, Blur and Pulp would’ve been regarded as alternative but because, and solely because, of the groundbreaking work we did, the alternative is now the mainstream!”

Johnny: “We fought a war for those young upstarts!”

And how have things changed personally?

Johnny: “My 20s were really, really intense. I’m 32 now and I’ve been making records for 14 years. When I turned 30 I started enjoying things that I’d missed in my teens.”

Bernard: “I’ve discovered that for me to be happy there’s got to be another reason for living other than getting shit-faced, after years and years of it. My pleasure now comes from enriching my brain. I’ve got to do things that make me a better person. Sound like a born-again Christian, don’t I? I just don’t want to burn myself out mentally or physically any more because it’s a waste of time. I don’t like parties or nightclubs any more because the end result was always the same. I’d walk home at eight in the morning, drunk and physically ill.”

Johnny: “Like you did last week?!”

Bernard: "That was a one off! But I’m not like Aerosmith. I’m really proud of my debauched past. I’ve done some really naughty things that I’ve really enjoyed, but now I want to generate energy within my life without taking it out all the time.”

It’s well known that you’ve taken Prozac. Did that help?

Johnny: “I didn't notice any difference.”

Did you take it too?

Johnny: “I meant with Bernard, but I did take it. I got bored when the side-effects wore off so I stopped."

Bernard: “What, the hard-on like a diamond cutter?! Great, yeah... but being a musician you can exist in a druggy environment - got to watch what I say here - so it's very appealing to have a legal drug to experiment with. It’s not like a street drug. When you take it you don’t feel off it. Once the side-effects settle down, you don’t feel on a drug. You don’t notice your personality change, but it does. All the negativity is filtered out. So if you have a problem, like your dad dying, you don’t crumble. You go, ‘My dad’s died. That’s bad. I’d better arrange a funeral'. So it’s a cool drug, but not what I’d expected, being used to the street variety.” There was that BBC documentary about artists who take Prozac that focused on you...

Bernard: “That programme was a load of crap. The agenda the guy gave to me was to prove or disprove that all artists are f—ed up. His idea was that if you gave an artist Prozac, his creativity would stop. So I agreed to do it. One, because I really wanted to try Prozac, two because the concept of the programme was interesting. What I didn’t like was that to prove his concept he had to annihilate everyone in the programme. He was trying to prove that we were all f—ed up and I wasn’t.”

Johnny: “We laughed our f—ing heads off when we saw it though. He’d focus on the pen and then he’d focus on Bernard. If you were trying to write a letter and some knobhead with a camera was following you around a tiny room you’d get blocked.”

Bernard: “He said I had hyper-critical voices in my head. We all have self-criticism, but if I had these hyper-critical voices in my head I’d hardly let them stand there filming me whilst I was writing. He said, too, that I had a writing block for a year but it just wasn’t true. But I did feel, I suppose, a little more shallow on Prozac. I don’t know if that affected my lyric writing, because a lot of my lyrics come from deep within the context of my brain..."

Johnny: “From deep within his huge cortex!”

Bernard: "Er, yes, a lot of my lyrics come from my subconscious. After we’ve written a song, I say, ‘That’s f—ing great,’ play the music and then I’ll write the lyrics within three hours.”

Johnny: "He did ‘Forbidden City’ within an afternoon.”

What’s it about?

Bernard: “It’s about a young man who lives with his father, it’s a one-parent family but the parent is a male. His father’s a drunk, he beats him up and it’s about getting away from him because he can see it's bad, but underneath there’s a tug of love. There’s a tie he can’t break. It’s about not respecting someone but being tied to them in an illogical way.”

Doesn't sound that subconscious.

Bernard: “I wrote the song and decided that was what it was about afterwards. If you decide beforehand it's bit like school essays. I think in pictures. Before music, art was my medium and then I had to learn this foreign medium. Words. When Ian (Curtis, singer of Joy Division) died and I became the lyricist I had no choice, it was my living. So one way of writing words is to get a picture in my head and describe it.”

Johnny: “Having worked with a few lyricists, the process that Bernard has just described gives each song a different personality because Bernard has an objectivity to his lyrics and how they relate to the music. Normally, someone who wants to be a lyricist wants to express themselves and their ideas over certain subjects. You find that over the course of a few LPs you’re getting kinda bogged down by this one person’s personality.

“Whereas having Bernard’s objectivity, which is brought about by the images that the music evokes, gives you a slightly different opinion over the course of a record. It’s a very pseudy way of putting it, but so what, I'm a pseud.

“My favourite lyric on the album is the most simple one, off ‘Dark Angel’. It’s: ‘Don’t think about it/Let me take you out.’ It just reminds me of playing dance records before going out when I was young. You didn’t want anyone’s opinion on anything, you didn't want personal angst. There’s a lot to be said for simple, direct lyrics like ‘Let The Music Play’ or ‘Into The Groove’. I defy anyone to say those are crap records simply because they’re not conveying some intellectual sentiment.”

You’ve both been in groups, though, where the lyrics are very important, groups that elevated the importance of lyrics.

“There’s a lot of people whose happiness will depend from week to week on what their favourite lyricist is sending them,” says Johnny. “Of course that’s an important function of music too. We aim to cover all bases in Electronic.”

AH, YES. The other groups. Will either The Smiths or New Order, the two British groups with the firmest grips on the imagination of ’80s youth, ever reappear?

New Order have only been out of circulation for three years and could well pop up again if, say, any of them get a particularly large gas bill. The Smiths, on the other hand, are the subject of persistent rumour, but nothing concrete has emerged in the past nine years. Morrissey has patently missed Marr professionally, if not personally, but not enough to entice a reunion. Still, the rumours continue...

“I tell you what's going to happen,” says Bernard. “I’m going to work with Morrissey and Johnny’s joined New Order.”

“I never get to hear these rumours,” lies Johnny. “I mean people said The Beatles were going to reform and look what happened. Oh, they did!”

Bernard: “I only saw Hooky, Steve and Gillian, what... two years ago?!”

Johnny: "All we’re arsed about is Electronic. There’s all sorts of rumours, but who knows?”

Do you have any contact with Morrissey?

Johnny: “Occasionally. Last time we met it was a really nice experience. It was really good to see him, especially since a... a feud that didn’t realty exist had become public property. And because of the relationship we had it was time to resolve it in private and do something ourselves because it was really quite a serious situation. I was tired of being involved in other people’s games and I wanted to do something for us. It sounds sentimental, but it’s very important. We’re all big boys, it’s not the school playground. I know it’s interesting for other people, but it's kinda private. I certainly don’t wish him - or anyone I’ve worked with - ill. Life’s too short.”

He stops and squeezes out a smile.

“Isn't that nice?”

Bernard takes a swig of wine and sluices it through his teeth before swigging it down and smacking his lips dramatically.

“I’m keeping my gob shut.”

THE RAIN, naturally, falls down on this manic town as Johnny and Bernard leave the hotel. Johnny’s off to buy a pair of jeans and Bernard, oh, Bernard might as well go too. He wants the same cut, but in a darker shade, y’know?

Before they depart from their split-level suite, Bernard kicks in with a selection of stories about various Mancunian music types, all of which are not only too libellous to print here but too damn dangerous. One that just squeaks through, about a member of New Order’s road crew, details all the things that said employee did that didn't earn him the sack.

Like, Bernard didn’t sack him when the guy was caught with his trousers down in the boardroom of the band's American label with a secretary. Bernard didn’t sack him when he wandered back through the office with lipstick marks across the zipper of his white trousers. Bernard didn’t sack him when he left thousands of the band’s dollars in a briefcase in a pool of mud after a US festival because somebody chatted him up... and so on.

BUT! Bernard had been suffering from a stomach virus throughout a US tour and had been unable to drink. So he arranged for some friends to visit on one date with some nonprescription pharmaceuticals. These drugs were given to the employee to look after until after the show. Can you guess? When Bernard came offstage and asked for his thingy, the guy laughed and said it was already whizzing through the guy’s bloodstream. That’s when Bernard sacked him.

“Too right!” yells Marr in impeccable mock-scally. “Losing all your takings is one thing, but nicking a guy’s bumble bee is bang out of order!”

Nowadays, of course, Bernard just says no to drugs. But he does say yes to sport. No, really.

“I liked Prozac,” he says, “I liked what it did. But I don't like the idea of a chemical squirting through my brain every day for the rest of my life in case it causes, say, brain cancer. But I found running has the same effect as Prozac. So I go running and I enjoy that. Well, I don’t enjoy it, it’s f—ing boring. But you feel great afterwards. I don’t want to be like Pete Townshend, boring everyone with my get clean campaign. I’m not a reformed character. I’m a changed character. Running makes me feel great. So that’s my new drug.”

He stops and that glint flickers back across his pupils.

“I’ve been doing it for at least a week now!”

The last we see of Johnny Marr and Bernard Sumner is from the back of a cab as they weave their way across the road. They’re both walking with their bodies half-turned towards each other, giggling. As they talk, Johnny momentarily throws his arm around Bernard's shoulders and they both burst out laughing, Johnny ruffling Bernard’s hair and shoving him off.

And then they whizz around the comer, Johnny pimp rolling and Bernard all hunched and bumbling, still laughing and gabbling like two best mates in the school playground heading off at the end of the day. Or maybe they’re more like two old biddies on their way to bingo. Or maybe they’re like a couple of young fathers on their way to the pub after the match. Or maybe...

Well, it’s Johnny Marr and Bernard Sumner, isn’t it? Just two little fellers off to buy some denim in the rain in Manchester.

Comments

Post a Comment