1997 12 13 Joy Division NME

KING CURTIS

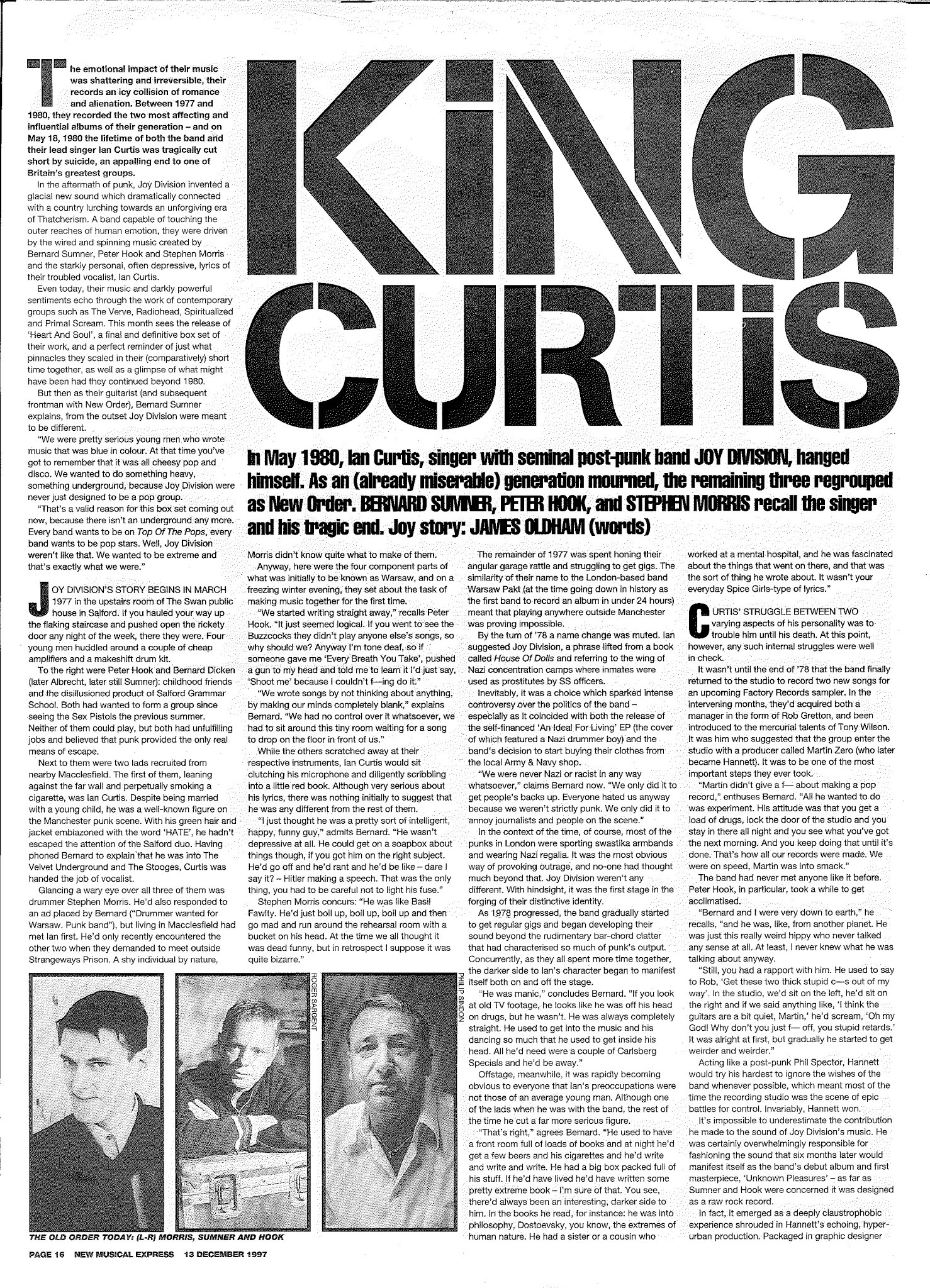

In May 1980, Ian Curtis, singer with seminal post-punk band JOY DIVISION, hanged himself. As an (already miserable) generation mourned, the remaining three regrouped as New Order. BERNARD SUMNER, PETER HOOK and STEPHEN MORRIS recall the singer and his tragic end. Joy story: JAMES OLDHAM (words)

In the aftermath of punk, Joy Division invented a glacial new sound which dramatically connected with a country lurching towards an unforgiving era of Thatcherism. A band capable of touching the outer reaches of human emotion, they were driven by the wired and spinning music created by Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook and Stephen Morris and the starkly personal, often depressive, lyrics of their troubled vocalist, Ian Curtis.

Even today, their music and darkly powerful sentiments echo through the work of contemporary groups such as The Verve, Radiohead, Spiritualized and Primal Scream. This month sees the release of 'Heart And Soul’, a final and definitive box set of their work, and a perfect reminder of just what pinnacles they scaled in their (comparatively) short time together, as well as a glimpse of what might have been had they continued beyond 1980.

But then as their guitarist (and subsequent frontman with New Order), Bernard Sumner explains, from the outset Joy Division were meant to be different.

“We were pretty serious young men who wrote music that was blue in colour. At that time you’ve got to remember that it was all cheesy pop and disco. We wanted to do something heavy, something underground, because Joy Division were never just designed to be a pop group.

"That's a valid reason for this box set coming out now, because there isn't an underground any more, Every band wants to be on Top Of The Pops, every band wants to be pop stars. Well, Joy Division weren’t like that. We wanted to be extreme and that’s exactly what we were.”

JOY DIVISION’S STORY BEGINS IN MARCH 1977 in the upstairs room of The Swan public house in Salford. If you hauled your way up the flaking staircase and pushed open the rickety door any night of the week, there they were. Four young men huddled around a couple of cheap amplifiers and a makeshift drum kit.

To the right were Peter Hook and Bernard Dicken (later Albrecht, later still Sumner): childhood friends and the disillusioned product of Salford Grammar School. Both had wanted to form a group since seeing the Sex Pistols the previous summer. Neither of them could play, but both had unfulfilling jobs and believed that punk provided the only real means of escape.

Next to them were two lads recruited from nearby Macclesfield. The first of them, leaning against the far wall and perpetually smoking a cigarette, was Ian Curtis. Despite being married with a young child, he was a well-known figure on the Manchester punk scene. With his green hair and jacket emblazoned with the word ‘HATE’, he hadn’t escaped the attention of the Salford duo. Having phoned Bernard to explain'that he was into The Velvet Underground and The Stooges, Curtis was handed the job of vocalist.

Glancing a wary eye over all three of them was drummer Stephen Morris. He’d also responded to an ad placed by Bernard (“Drummer wanted for Warsaw. Punk band”), but living in Macclesfield had met Ian first. He’d only recently encountered the other two when they demanded to meet outside Strangeways Prison. A shy individual by nature, Morris didn’t know quite what to make of them.

Anyway, here were the four component parts of what was initially to be known as Warsaw, and on a freezing winter evening, they set about the task of making music together for the first time.

“We started writing straight away,” recalls Peter Hook. “It just seemed logical. If you went to see the Buzzcocks they didn’t play anyone else’s songs, so why should we? Anyway I’m tone deaf, so if someone gave me ‘Every Breath You Take’, pushed a gun to my head and told me to learn it I’d just say, ‘Shoot me’ because I couldn’t f—ing do it.”

“We wrote songs by not thinking about anything, by making our minds completely blank,” explains Bernard. “We had no control over it whatsoever, we had to sit around this tiny room waiting for a song to drop on the floor in front of us.”

While the others scratched away at their respective instruments, Ian Curtis would sit clutching his microphone and diligently scribbling into a little red book. Although very serious about his lyrics, there was nothing initially to suggest that he was any different from the rest of them.

“I just thought he was a pretty sort of intelligent, happy, funny guy,” admits Bernard. “He wasn’t depressive at all. He could get on a soapbox about things though, if you got him on the right subject. He’d go off and he’d rant and he’d be like - dare I say it? - Hitler making a speech. That was the only thing, you had to be careful not to light his fuse.”

Stephen Morris concurs: “He was like Basil Fawlty. He’d just boil up, boil up, boil up and then go mad and run around the rehearsal room with a bucket on his head. At the time we all thought it was dead funny, but in retrospect I suppose it was quite bizarre.”

The remainder of 1977 was spent honing their angular garage rattle and struggling to get gigs. The similarity of their name to the London-based band Warsaw Pakt (at the time going down in history as the first band to record an album in under 24 hours) meant that playing anywhere outside Manchester was proving impossible.

By the turn of ’78 a name change was muted. Ian suggested Joy Division, a phrase lifted from a book called House Of Dolls and referring to the wing of Nazi concentration camps where inmates were used as prostitutes by SS officers.

Inevitably, it was a choice which sparked intense controversy over the politics of the band - especially as it coincided with both the release of the self-financed ‘An Ideal For Living’ EP (the cover of which featured a Nazi drummer boy) and the band’s decision to start buying their clothes from the local Army & Navy shop.

“We were never Nazi or racist in any way whatsoever,” claims Bernard now. “We only did it to get people’s backs up. Everyone hated us anyway because we weren’t strictly punk. We only did it to annoy journalists and people on the scene.”

In the context of the time, of course, most of the punks in London were sporting swastika armbands and wearing Nazi regalia. It was the most obvious way of provoking outrage, and no-one had thought much beyond that. Joy Division weren’t any different. With hindsight, it was the first stage in the forging of their distinctive identity.

As 1978 progressed, the band gradually started to get regular gigs and began developing their sound beyond the rudimentary bar-chord clatter that had characterised so much of punk’s output. Concurrently, as they all spent more time together, the darker side to Ian’s character began to manifest itself both on and off the stage.

“He was manic,” concludes Bernard. "If you look at old TV footage, he looks like he was off his head on drugs, but he wasn’t. He was always completely straight. He used to get into the music and his dancing so much that he used to get inside his head. All he’d need were a couple of Carlsberg Specials and he’d be away.”

Offstage, meanwhile, it was rapidly becoming obvious to everyone that Ian’s preoccupations were not those of an average young man. Although one of the lads when he was with the band, the rest of the time he cut a far more serious figure.

“That’s right,” agrees Bernard. “He used to have a front room full of loads of books and at night he’d get a few beers and his cigarettes and he’d write and write and write. He had a big box packed full of his stuff. If he’d have lived he’d have written some pretty extreme book - I’m sure of that. You see, there’d always been an interesting, darker side to him. In the books he read, for instance: he was into philosophy, Dostoevsky, you know, the extremes of human nature. He had a sister or a cousin who worked at a mental hospital, and he was fascinated about the things that went on there, and that was the sort of thing he wrote about. It wasn’t your everyday Spice Girls-type of lyrics.”

CURTIS’ STRUGGLE BETWEEN TWO varying aspects of his personality was to trouble him until his death. At this point, however, any such internal struggles were well in check.

It wasn’t until the end of '78 that the band finally returned to the studio to record two new songs for an upcoming Factory Records sampler. In the intervening months, they’d acquired both a manager in the form of Rob Gretton, and been introduced to the mercurial talents of Tony Wilson. It was him who suggested that the group enter the studio with a producer called Martin Zero (who later became Hannett). It was to be one of the most important steps they ever took.

“Martin didn’t give a f— about making a pop record,” enthuses Bernard. “All he wanted to do was experiment. His attitude was that you get a load of drugs, lock the door of the studio and you stay in there all night and you see what you’ve got the next morning. And you keep doing that until it’s done. That’s how all our records were made. We were on speed, Martin was into smack.”

The band had never met anyone like it before. Peter Hook, in particular, took a while to get acclimatised.

“Bernard and I were very down to earth,” he recalls, “and he was, like, from another planet. He was just this really weird hippy who never talked any sense at all. At least, I never knew what he was talking about anyway.

“Still, you had a rapport with him. He used to say to Rob, ‘Get these two thick stupid c—s out of my way’. In the studio, we’d sit on the left, he’d sit on the right and if we said anything like, ‘I think the guitars are a bit quiet, Martin,’ he’d scream, ‘Oh my God! Why don’t you just f— off, you stupid retards.’ It was alright at first, but gradually he started to get weirder and weirder.”

Acting like a post-punk Phil Spector, Hannett would try his hardest to ignore the wishes of the band whenever possible, which meant most of the time the recording studio was the scene of epic battles for control. Invariably, Hannett won.

It’s impossible to underestimate the contribution he made to the sound of Joy Division’s music. He was certainly overwhelmingly responsible for fashioning the sound that six months later would manifest itself as the band’s debut album and first masterpiece, ‘Unknown Pleasures’ - as far as Sumner and Hook were concerned it was designed as a raw rock record.

In fact, it emerged as a deeply claustrophobic experience shrouded in Hannett’s echoing, hyper-urban production. Packaged in graphic designer Peter Saville’s evocative black and white sleeve, it was an album of immense gravitas that contained a frequently harrowing, virtually unmatchable emotional impact.

Curtis’ poignant and alienated iyrics combined with the nasal harshness of his voice to create an atmosphere at times bordering on unmitigated despair. Understandably, the album received gushing reviews, and Joy Division’s reputation was cemented.

UNBEKNOWN TO ANYONE, HOWEVER, IN the period prior to the release of ‘Unknown Pleasures’, the seeds of Joy Division’s destruction had already been sown. On December 27, 1978, on the journey home from a gig at London’s Hope & Anchor, lan Curtis suffered his first epileptic fit.

At first, the others simply thought he was fooling around, but when it didn’t stop they were forced to swerve into a motorway lay-by and hold him down for ten minutes until the fit passed. That same night they drove him to Luton Hospital and it was there that he was diagnosed as having epilepsy.

“We just dreaded that it was going to be the end of the group really,” states Bernard. “We’d worked so hard, we used to pay to go onstage, it was just starting to happen and we thought, ‘Oh no, things are going to fall apart’. Which they did really."

Rationally, it should have been the end of the group. Ian’s instructions were to not stay up late, drink, have any excitement or stand in front of any flashing lights. It made life in a band almost impossible. On top of this he was also prescribed extremely heavy barbiturates designed to stop him having any more fits. All the drugs seemed to do was to make him depressed.

“It was a gradual thing,” reveals Bernard, “but if you look at some of the later photographs, his physical appearance went down. There are some where he looks really dishevelled and unshaven.

“I don’t think it was just because of his fits, it’s just that if you’re depressed you cave in and think the whole world is against you and what’s more you think there’s nothing you can do about it. If he hadn’t been on those drugs then maybe he could have resolved his problems.”

As for the suggestion that he’d somehow been obsessed with epilepsy prior to having his first fit, Morris thinks that any such claims have been exaggerated: “He knew someone who had epilepsy and he’d read Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. That’s it.”

Either way, as 1979 continued, his fits became more pronounced and various members of the band were frequently called upon to deal with him. Peter Hook, in particular, has some very disturbing memories of that period.

‘The guy used to rattle, he really did. All I used to do was jump on his chest, hold his tongue and make sure he didn’t joss it. The guy was really ill, everything was going wrong, it was a mess.”

As it was, the success of ‘Unknown Pleasures’ only increased the strain on Curtis. Their touring schedule was now more hectic and in autumn ’79 they undertook a major tour with the Buzzcocks. It was during a break from these gigs in the middle of October that lan first met Annik Honore - a Belgian woman masquerading as a journalist who became his mistress. Matters were starting to accelerate.

Without doubt, the guilt lan Curtis subsequently felt over this affair was intense and acted as yet another destabilising force on his already fragile mental state. At the time, the rest of the band were ambivalent about the relationship, believing that it wouldn’t last.

“Hmm,” sighs Stephen, “Annik. (Pause) Talk about getting deeper into it. It didn’t help at all. I think he just wanted to change something about his fife, but he didn’t really know what it was. 1 know he felt very guilty about it, and we didn’t help because we just gave him grief ail the time. She was a vegetarian, so we always used to try to get him to come for a kebab if she was around.

“I remember recording ‘Closer’ and she thought it was terrible. She kept saying, ‘It sounds like Genesis’, lan was frantic, he thought we were going to have to remix it all.”

Ian’s life was now in freefall. In the few months before they entered the Britannia Row studios in London to record ‘Closer’, the signs became increasingly apparent. Most visibly, in January 1980, lan was found by his wife Deborah clutching a copy of The Bible having just slashed his chest apart. Everything was reaching a conclusion, a fact reflected in the intensely personal lyrics which he was writing as they entered the studio.

“I remember being at Britannia Row,” recounts Bernard, “and asking lan whether he was feeling alright because he’d been acting strangely for days, and he said, ‘It feels like I’m caught in a whirlpool and I’m being dragged down and sucked under water’. I think even then he had dark thoughts about committing suicide which he never shared with us. it was like he felt this was his destiny.”

Immediately after the ‘Closer’ sessions, the band played a gig with The Stranglers on April 4. It was here that lan had his most serious fit yet. Three days later, he took an overdose of phenobarbitone and was confined to hospital. The next day, the band dragged him from his bed to perform in Bury. He managed two songs before collapsing, leaving the audience to riot and him in tears.

Around the same time, his wife filed for divorce. Ian, after a brief spell at his parents’ home, went to stay with Bernard where his friend frantically tried to lift his spirits, at one point even hypnotising him.

“I was interested in hypnotic regression,” he reveals, “and I hypnotised lan and taped our conversation. Afterwards he didn’t remember anything so I gave him the tape. I’ve always wondered, ‘F—ing hell, was that the wrong thing to do?’ I’ve never hypnotised anyone since and maybe there was something on that tape. Either way, he committed suicide a week later.”

Stephen Morris has his own interpretation: “It could have been my car stereo. I bought a cassette player that no-one liked, which mysteriously got stolen one night, I think it ruined all of Ian’s Doors tapes, which pissed him off. It really was the worst cassette player in the world, absolutely terrible...”

The phone call arrived on May 19. The band had played what was to be their final gig at Birmingham University two weeks earlier, and were on the verge of releasing ‘Closer’, one of the greatest albums of all time, as well as embarking on their first trip to America.

When the sun had risen, lan - who’d stayed up all night drinking whisky and writing a letter to his wife - walked into the kitchen of his marital home and hanged himself. Like Kurt Cobain’s suicide a decade and a half later, it was an act of complete despair that served as tragic proof of the realism and intensity of his lyrics. It was also an act that froze Joy Division’s work at its peak and acted as a hammer blow to the hearts of all those that surrounded him.

One month later, ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ became the band’s first Top 30 hit and on July 26, ‘Closer’ entered the album charts at Number Six.

SEVENTEEN YEARS LATER, HIS MEMORY IS still difficult to deal with. “When I picture Ian now,” explains Bernard, “I picture him as he was in the photographs. I don’t like to picture his personality because it’s too upsetting. It’s the same with the records, I find ‘Closer' and ‘Unknown Pleasures’ too heavy to hear, but that’s because I’m looking from the inside.

“I don’t live far away now from where he lived and was later cremated. Sometimes I go for a drive in the hills and I always have to drive past the crematorium and I have to think about him. I don’t have to ask why because I think 1 know why he did it. If he hadn’t been on those drugs... To be honest, the whole Michael Hutchence thing has brought a lot of it flooding back.”

All concerned, however, are still justifiably proud of the music they created, and if there’s any real legacy it’s the profound effect those two albums had on subsequent generations - from U2 through to The Charlatans. Like any classic records, they remain as startling today as they were then.

“Even now,” says Peter Hook proudly, “I’d put Joy Division up against anybody, anybody at all. It’s amazing that four people could make something that powerful. Can you think of a better, heavier band? I’m still proud of it...”

Like we say, the tremors are still being felt.

Comments

Post a Comment